A true cineaste, a friend once told me, will have the most eclectic “best of” list, forged from a deep love of cinema and an absolute confidence in their choices. There will be no looking at a Great Movies book, no consideration of public taste. They have not a care for legacies or film schools. That’s why this recently unearthed list of Stephen Sondheim’s favorite films is such a fascinating read.

The composer passed away last month at 91, having changed Broadway musicals from big and brassy popular fare into something that could tackle strange and experimental themes and stories yet be just as successful. He provided the lyrics for West Side Story and Gypsy, and then went on to a string of challenging hits: Company, Follies, A Little Night Music, Sweeney Todd, Into the Woods, Assassins.

The subject matters he tackled were often dark and complex. He watched many of his musicals get the Hollywood treatment, occasionally wrote songs for cinema, and toyed with adapting several films for the stage, including Being There and Sunset Boulevard. So what must his film list be like?

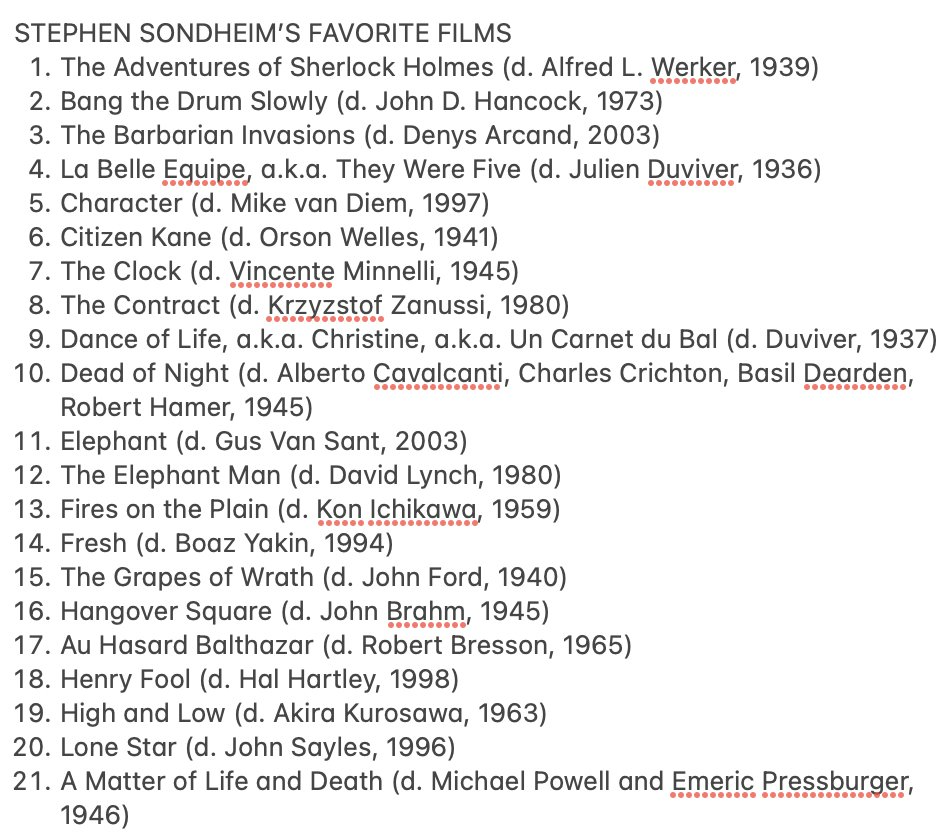

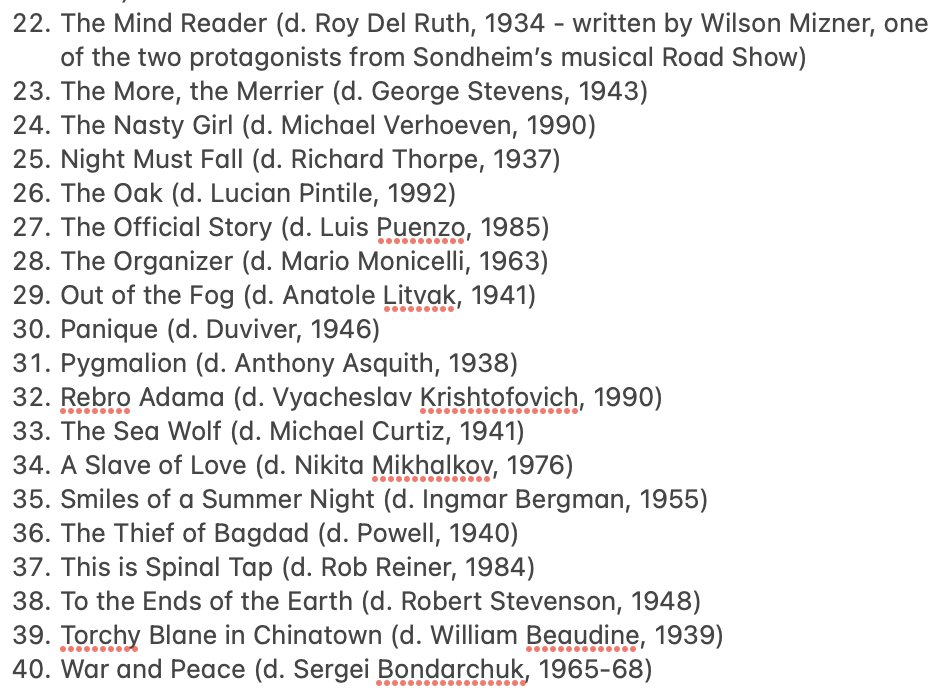

Really odd, is the answer. The published list is in alphabetical order, and there are very few classics in there—Welles’ Citizen Kane, Bergman’s Smiles on a Summer Night, Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar, and Kurosawa’s High and Low.

Conspicuously missing: other musicals.

“The only kind of movie that held no interest for me whatsoever was musical,” he told the New York Times in 2003. ”We’re talking about from the age of 10 to the age of 25. I knew the musicals because I would hear the songs, but I never went out of my way to see them. Not the fabulous Arthur Freed MGM unit, and it’s not that I thought they were bad. It’s what I loved were westerns. Melodramas, even romantic comedies. High drama.’’

The interview suggests a method to the list—these were films Sondheim loved but most had not seen; he would insist friends and collaborators watch them. That’s how he describes 1980’s The Contract, directed by Krzysztof Zanussi, a “movie of his I find so extraordinary, I want to share it with everybody,’’ he said.

Born in 1930, Sondheim’s favorite decade (by movie count) is his teenage years, from the fantasy of Michael Powell’s The Thief of Bagdad to the horror of Dead of Night. Later years are more scattershot, with Lynch’s The Elephant Man and Rob Reiner’s This Is Spinal Tap being stand-out choices. His 1990s selections, right up through the mid-2000s show his continuing interest in dark themes (Gus Van Zant’s school shooting mood piece Elephant), large novelistic intertwining narratives (John Sayles’ Lone Star) and complicated family dramas (Denys Arcand’s The Barbarian Invasions).

Sondheim fans will find much to chew over on this list, that is, if they’ve even seen most of them. My percentage is admittedly low, let us know yours in the comments.

Related Content:

Watch Stephen Sondheim (RIP) Teach a Kid How to Sing “Send In the Clowns”

Martin Scorsese Names His Top 10 Films in the Criterion Collection

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.

Stephen Sondheim’s 40 Favorite Films is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3DG1UwI

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment