Children are the perfect audience for The Nutcracker.

(Well, children and the grandmothers who can’t wait for the toddler to start sitting still long enough to make the holiday-themed ballet an annual tradition…)

Maurice Sendak, the celebrated children’s book author and illustrator, agreed, but found the standard George Balanchine-choreographed version so treacly as to be unworthy of children, dubbing it the “most bland and banal of ballets.”

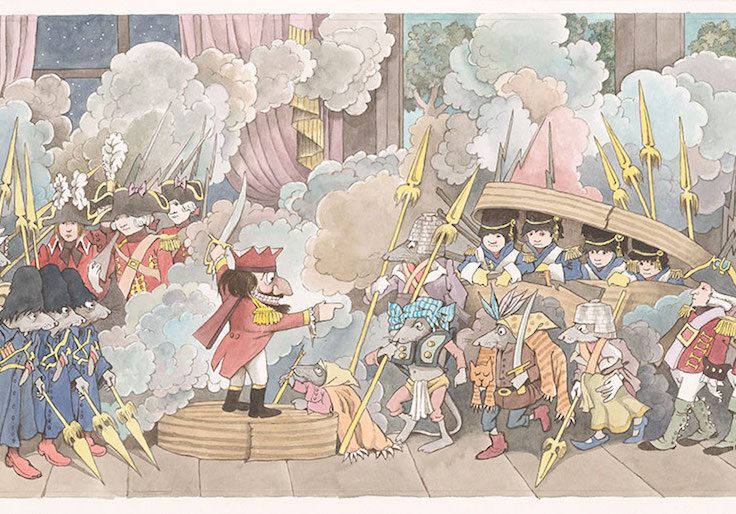

The 1983 production he collaborated on with Pacific Northwest Ballet artistic directors Kent Stowell and Francia Russell did away with the notion that children should be “coddled and sweetened and sugarplummed and kept away from the dark aspects of life when there is no way of doing that.”

Tchaikovsky’s famous score remained in place, but Sendak and Stowell ducked the source material for, well, more source material. As per the New York City Ballet’s website, the Russian Imperial Ballet’s chief ballet master, Marius Petipa, commissioned Tchaikovsky to write music for an adaptation of Alexander Dumas’ child-friendly story The Nutcracker of Nuremberg. But The Nutcracker of Nuremberg was inspired by the much darker E.T.A. Hoffman tale, 1816’s “The Nutcracker and the Mouse King.”

The “weird, dark qualities” of the original were much more in keeping with Sendak’s self proclaimed “obsessive theme”: “Children surviving childhood.”

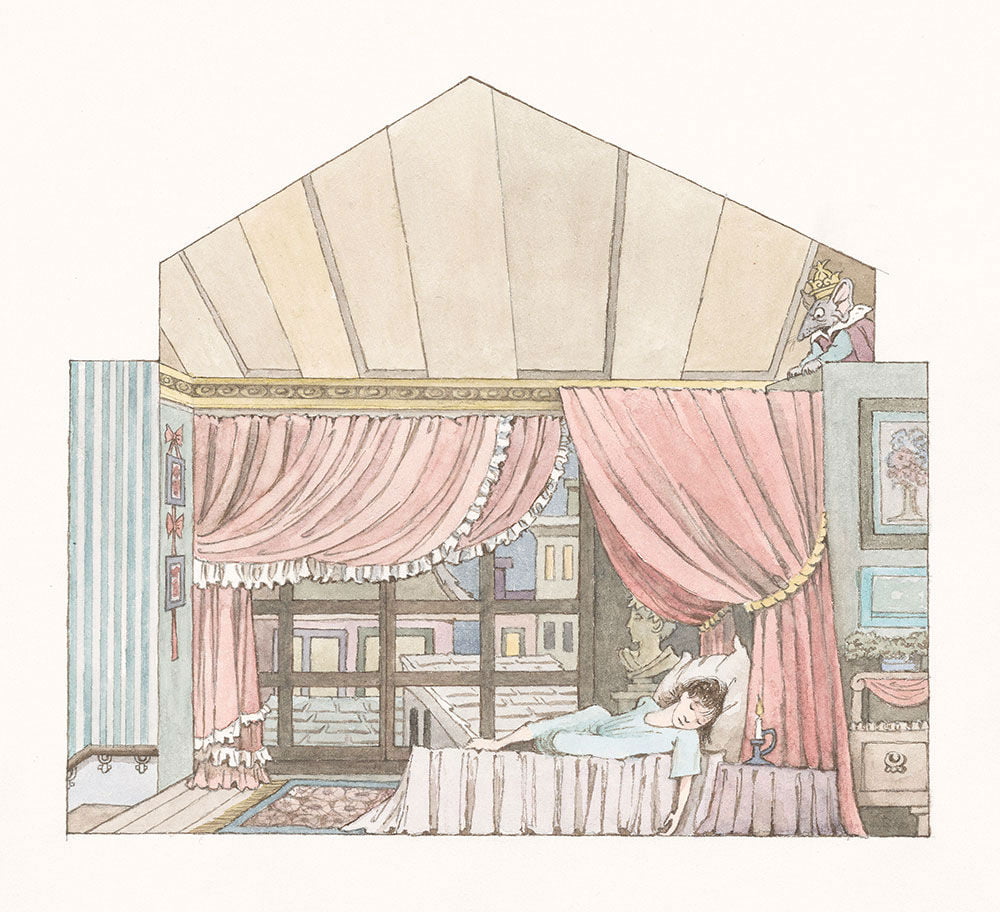

Sendak wanted the ballet to focus more intently on Clara, the young girl who receives the Nutcracker as a Christmas present in Act I:

It’s about her victory over her fear and her growing feelings for the prince… She is overwhelmed with growing up and has no knowledge of what this means. I think the ballet is all about a strong emotional sense of something happening to her, which is bewildering.

Balanchine must have felt differently. He benched Clara in Act II, letting the adult Sugarplum Fairy take centerstage, to guide the children through a passive tour of the Land of Sweets.

As Sendak scoffed to the Dallas Morning News:

It’s all very, very pretty and very, very beautiful… I always hated the Sugarplum Fairy. I always wanted to whack her.

“Like what kids really want is a candy kingdom. That shortchanges children’s feelings about life,” echoes Stowell, who revived the Sendak commission, featuring the illustrator’s sets and costumes every winter for 3 decades.

In lieu of the Sugar Plum Fairy, Sendak and Stowell introduced a dazzling caged peacock — a fan favorite played by the same dancer who plays Clara’s mother in Act I.

The threats, in the form of eccentric uncle Drosselmeier, a ferocious tiger, and a massive rat puppet with an impressive, pulsing tail, have a Freudian edge.

The painted backdrops, growing Christmas tree, and Nutcracker toy look as if they emerged from one of Sendak’s books. (He followed up the ballet by illustrating a new translation of the Hoffman original.)

The Sendak-designed costumes are more understated, thought Pacific Northwest Ballet costumer Mark Zappone, who described working with Sendak as “an incredible joy and pleasure” and recalled the funny ongoing battle with the Act II Moors costumes to Seattle Met:

Maurice’s design had the women in quite billowy pants. So we ripped them out of the box, threw them on the girls upstairs in the studios, and Kent started rehearsing the Moors. And one by one, the girls got their legs stuck in those pants and—boom—hit the floor, all six of them. It was like, “Oh my God, what are we going to do about that one?” They ended up, for years, twisting the legs in their costumes and making a little tuck here and there. It was a rite of passage; if you were going to do the Moors, don’t forget to twist your pants around so you won’t get stuck in them.

Rent a filmed version of Maurice Sendak’s The Nutcracker on Amazon Prime. (Look for a Wild Thing cameo in the boating scene with Clara and her Prince.)

Related Content:

The Only Drawing from Maurice Sendak’s Short-Lived Attempt to Illustrate The Hobbit

Maurice Sendak Sent Beautifully Illustrated Letters to Fans — So Beautiful a Kid Ate One

Maurice Sendak Illustrates Tolstoy in 1963 (with a Little Help from His Editor)

Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primaologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

When Maurice Sendak Created a Dark Nutcracker Ballet is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/32jpbbc

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment