The Story of Elizebeth Friedman, the Pioneering Cryptologist Who Thwarted the Nazis & Got Burned by J. Edgar Hoover

Elizebeth S. Friedman: Suburban Mom or Ninja Nazi Hunter?

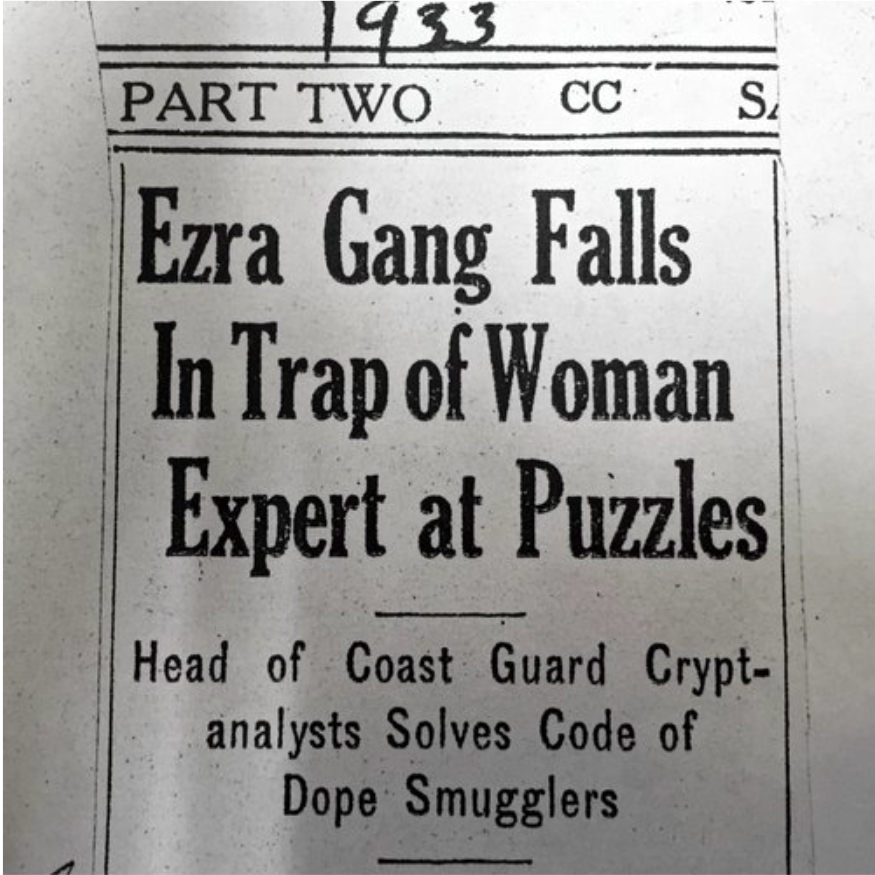

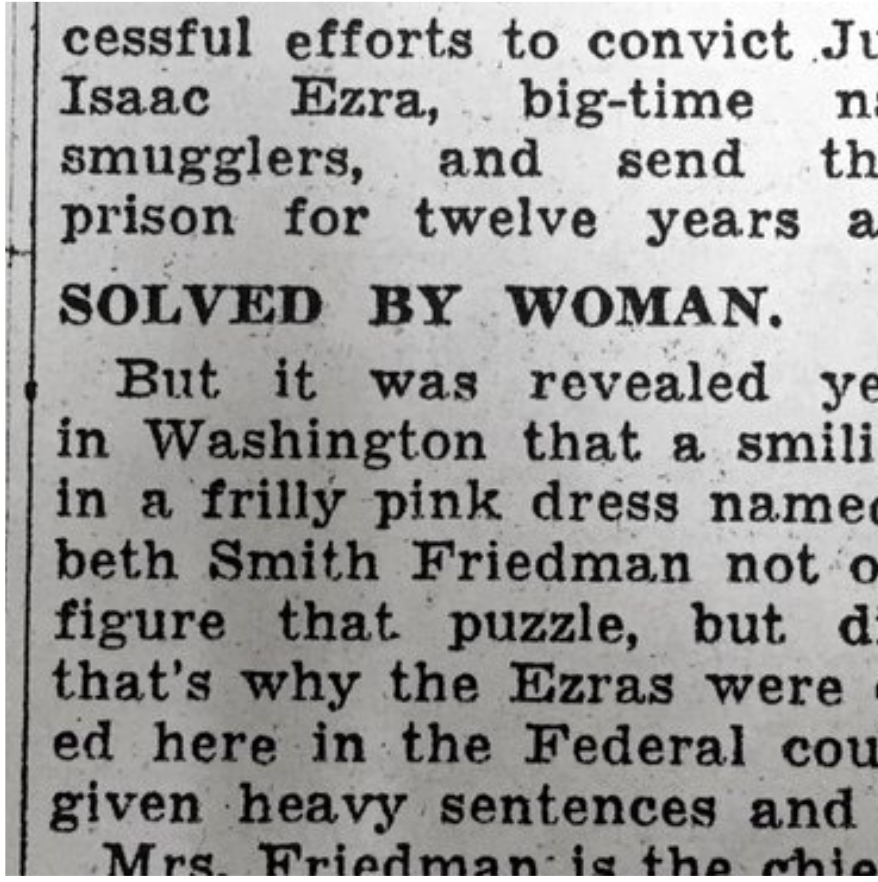

Both, though in her lifetime, the press was far more inclined to fixate on her ladylike aspect and homemaking duties than her career as a self-taught cryptoanalyst, with headlines such as “Pretty Woman Who Protects United States” and “Solved By Woman.”

The novelty of her gender led to a brief stint as America’s most recognizable codebreaker, more famous even than her fellow cryptologist, husband William Friedman, who was instrumental in the founding of the National Security Agency during the Cold War.

Renowned though she was, the highly classified nature of her work exposed her to a security threat in the person of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover.

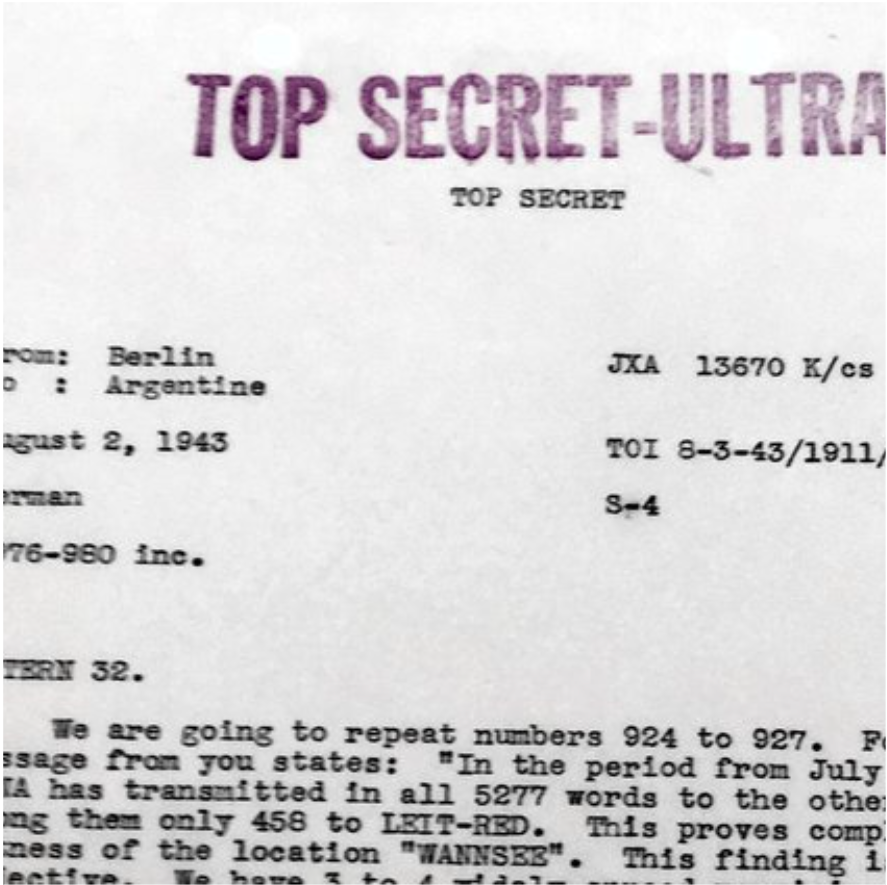

Hoover credited the FBI, and by extension, himself, for deciphering some 50 Nazi radio circuits’ codes, at least two of them protected with Enigma machines.

He also rushed to raid South American sources in his zeal to make an impression and advance his career, scuppering Friedman’s mission by causing Berlin to put a stop to all transmissions to that area.

Too bad no one asked him to demonstrate the methods he’d used to crack these impossible nuts.

The German agents used the same codes and radio techniques as the Consolidated Exporters Corporation, a mob-backed rum-running operation whose codes and ciphers Elizebeth had translated as chief cryptologist for the U.S. Treasury Department during Prohibition.

As an expert witness in the criminal trial of international rumrunner Bert Morrison and his associates, she modestly asserted that it was “really quite simple to decode their messages if you know what to look for,” but the sample decryption she provided the jury made it plain that her work required tremendous skill. The Mob Museum’s Jeff Burbank sets the scene:

She read a sample message, referring to a brand of whiskey: “Out of Old Colonel in Pints.” She showed how the three “o” and “l” letters in “Colonel” had identical cipher code letters. From the cipher’s letters for “Colonel” she could figure out the letter the racketeers chose for “e,” the most frequently occurring letter in English, based on other brand names of liquor they mentioned in other messages. The “o” and “l” letters in “alcohol,” she said, had the same cipher letters as “Colonel.”

Cinchy, right?

Elizebeth’s biographer, Jason Fagone, notes that in discovering the identity, codename and ciphers used by German spy network Operation Bolívar‘s leader, Johannes Siegfried Becker, she succeeded where “every other law enforcement agency and intelligence agency failed. She did what the FBI could not do.”

Sexism and Hoover were not the only enemies.

William Friedman’s criticism of the NSA for classifying documents he thought should be a matter of public record led to a rift resulting in the confiscation of dozens of papers from the couple’s home that documented their work.

This, together with the 50-year “TOP SECRET ULTRA” classification of her WWII records, ensured that Elizebeth’s life would end beneath “a vast dome of silence.”

Recognition is mounting, however.

Nearly 20 years after her 1980 death, she was inducted into the National Security Agency’s Cryptologic Hall of Honor as “a pioneer in code breaking.”

A National Security Agency building now bears both Friedmans’ names.

The U.S. Coast Guard will soon be adding a Legend Class Cutter named the USCGC Friedman to their fleet.

In addition to Fagone’s biography, a picture book, Code Breaker, Spy Hunter: How Elizebeth Friedman Changed the Course of Two World Wars, was published earlier this year.

As far as we know, there are no picture books dedicated to the pioneering work of J. Edgar Hoover….

Elizebeth Friedman, via Wikimedia Commons

Watch The Codebreaker, PBS’s American Experience biography of Elizebeth Friedman here.

Related Content:

The Enigma Machine: How Alan Turing Helped Break the Unbreakable Nazi Code

How British Codebreakers Built the First Electronic Computer

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her June 7 for a Necromancers of the Public Domain: The Periodical Cicada, a free virtual variety honoring the 17-Year Cicadas of Brood X. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

The Story of Elizebeth Friedman, the Pioneering Cryptologist Who Thwarted the Nazis & Got Burned by J. Edgar Hoover is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3wpdito

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment