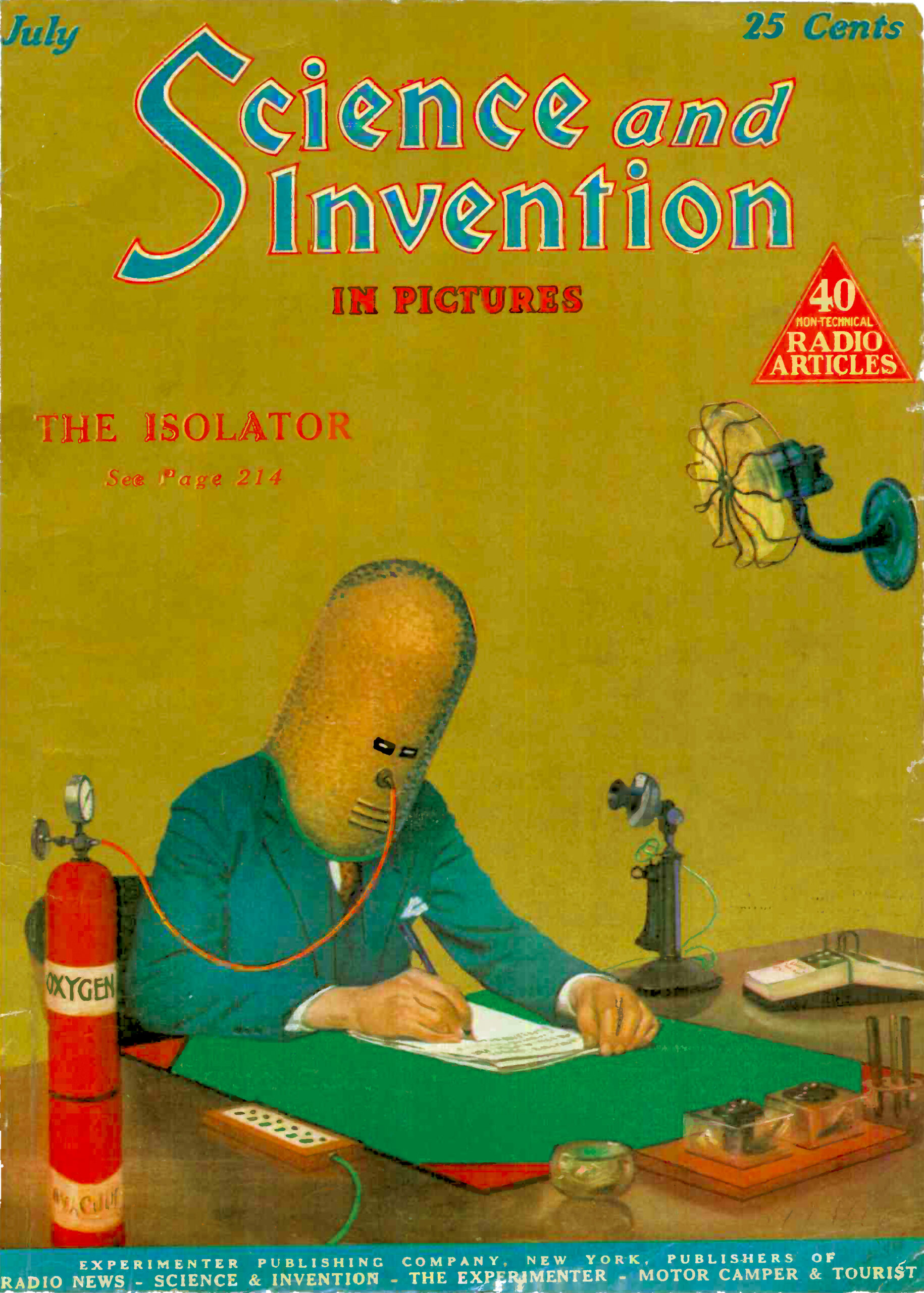

The Isolator: A 1925 Helmet Designed to Eliminate Distractions & Increase Productivity (Created by SciFi Pioneer Hugo Gernsback)

The anti-distraction device is the modern mousetrap: build a better one, and the world will beat a path to your door. Or so, at least, will the part of the world engaged in the pursuits we’ve broadly labeled “knowledge work.” Even among the knowledge workers who’ve spent most of the past year in pandemic-prompted isolation, many still feel besieged by unending claims on their attention. Laments at having been rendered unproductive by constant distraction go back at least to medieval times, but the proposed solutions to this long-standing problem change with — and reflect — the times. Take the “Isolator,” the formidable-looking wearable machine above that debuted on the cover of July 1925’s Science and Invention magazine.

“Perhaps the most difficult thing that a human being is called upon to face is long, concentrated thinking,” writes inventor Hugo Gernsback in the accompanying article. “Most people who desire thus to concentrate find it necessary to shut themselves up in an almost soundproof room in order to go ahead with their work, but even here there are many things that distract their attention.”

Even absent such nuisances as “street noises” and the “telephone bell,” the mind seeks out its own distractions as if naturally compelled: “You will lean back in your chair and begin to study the pattern of the wallpaper, or you will see a fly crawl along the wall, or a window curtain will be moving back and forth, all of which is often sufficient to turn your mind away from the immediate task to be performed.”

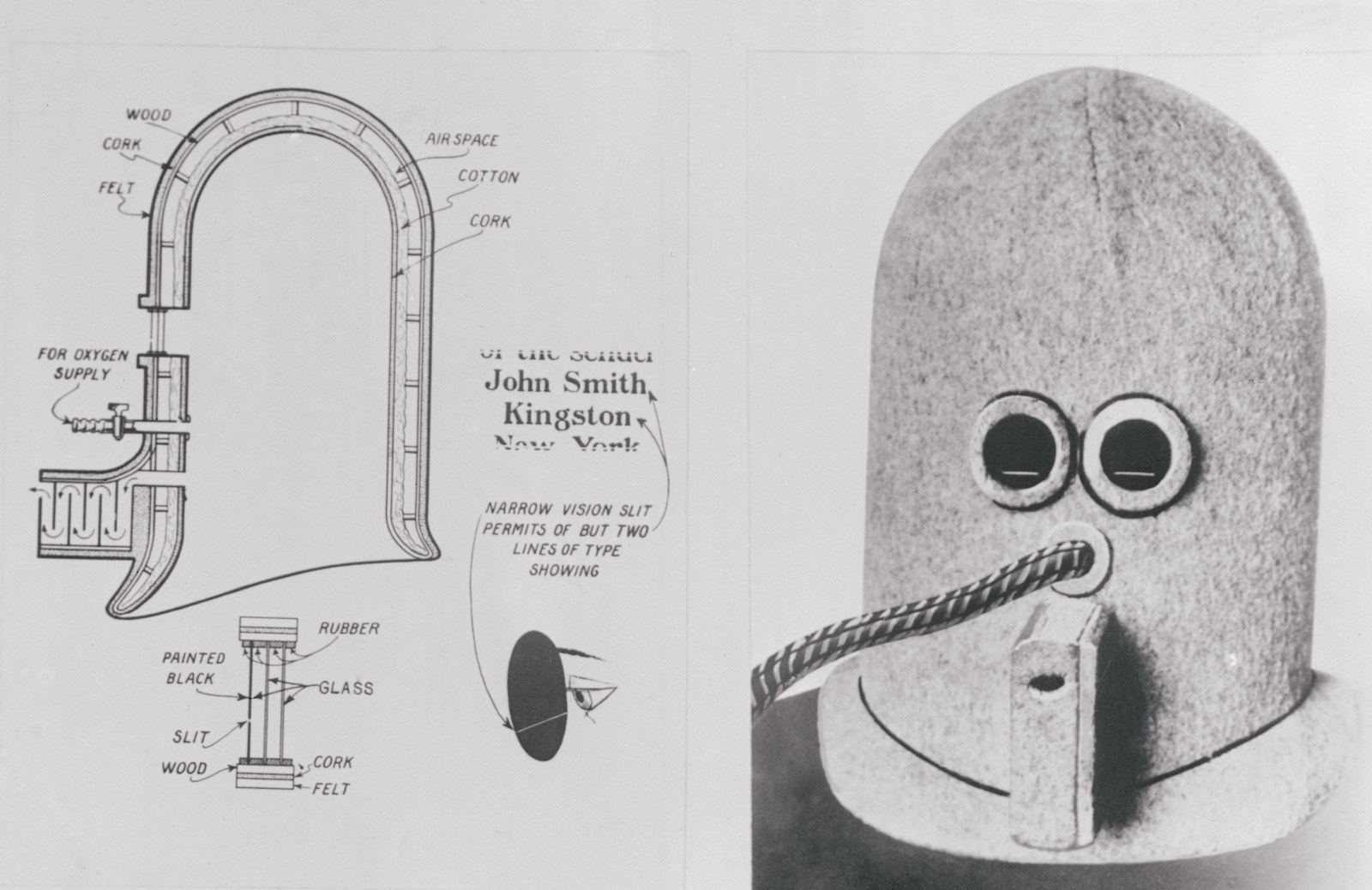

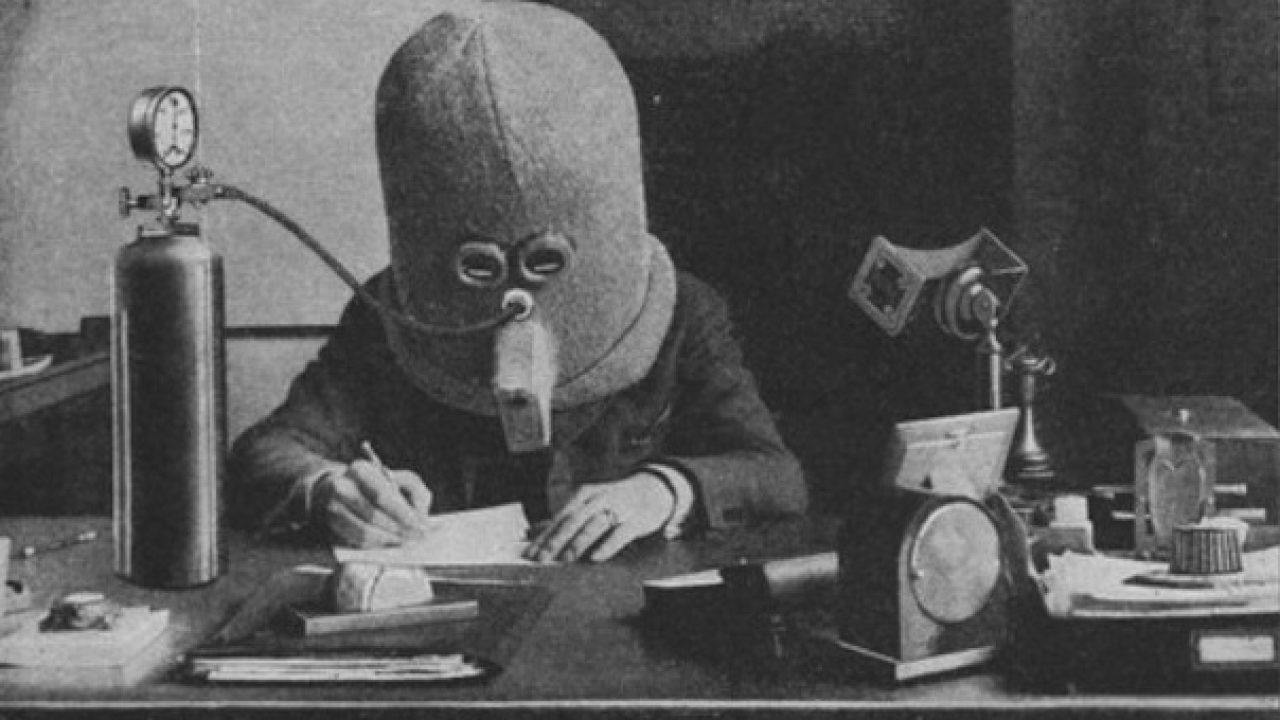

Gernsback’s solution involves a large helmet, lined with cork and covered in felt, with a baffle for breathing and glass eyeholes to see through. Painted black but for two thin bands, the eyeholes make it “almost impossible to see anything except a sheet of paper in front of the wearer. There is, therefore, no optical distraction here.” To prevent drowsiness, “the writer introduced a small oxygen tank, attached to the helmet. This increases the respiration and livens the subject considerably.” And so we arrive at the setup pictured below, originally captioned, “The author at work in his private study aided by the Isolator. Outside noises being eliminated, the worker can concentrate with ease upon the subject at hand.” The Isolator’s patent appears just above, one of 80 for various inventions that Gernsback held in his lifetime.

Whatever the device contributed to Gernsback’s productivity, there can be no question that the man got a lot done. Not just a contributor to Science and Invention but also its publisher, he oversaw a small media empire whose other periodicals included Everyday Science and Mechanics, Scientific Detective Monthly, the sinister-sounding Technocracy Review, and Amazing Stories, which launched in 1926 as the first magazine devoted entirely to science fiction (or “scientifiction,” as Gernsback called it). For his advancement of the genre he was honored by the World Science Fiction Society’s Annual Achievement Awards, better known as the “Hugos.” Pulp-fictional though the Isolator may have looked in 1925 (as indeed it looks now), it represents a genuine effort to alleviate with technology a bothersome aspect of the human condition — and a precedent for the new-and-improved isolation helmets engineered for the even more distracting world in which we live a century on.

Related Content:

How to Focus: Five Talks Reveal the Secrets of Concentration

The Benefits of Boredom: How to Stop Distracting Yourself and Get Creative Ideas Again

Medieval Monks Complained About Constant Distractions: Learn How They Worked to Overcome Them

What Happens When You Spend Weeks, Months, or Years in Solitary Confinement

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

The Isolator: A 1925 Helmet Designed to Eliminate Distractions & Increase Productivity (Created by SciFi Pioneer Hugo Gernsback) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3efMGoK

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment