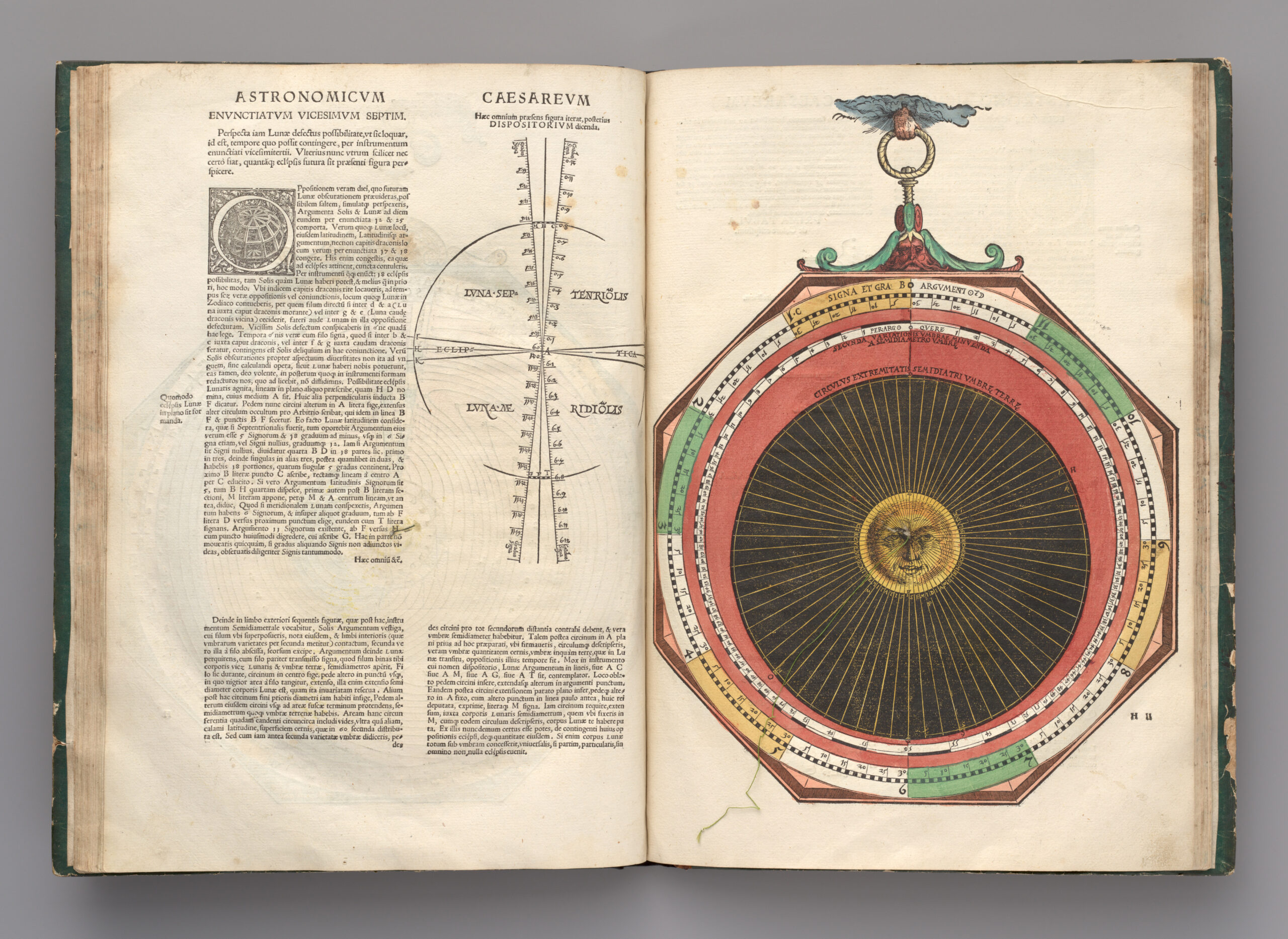

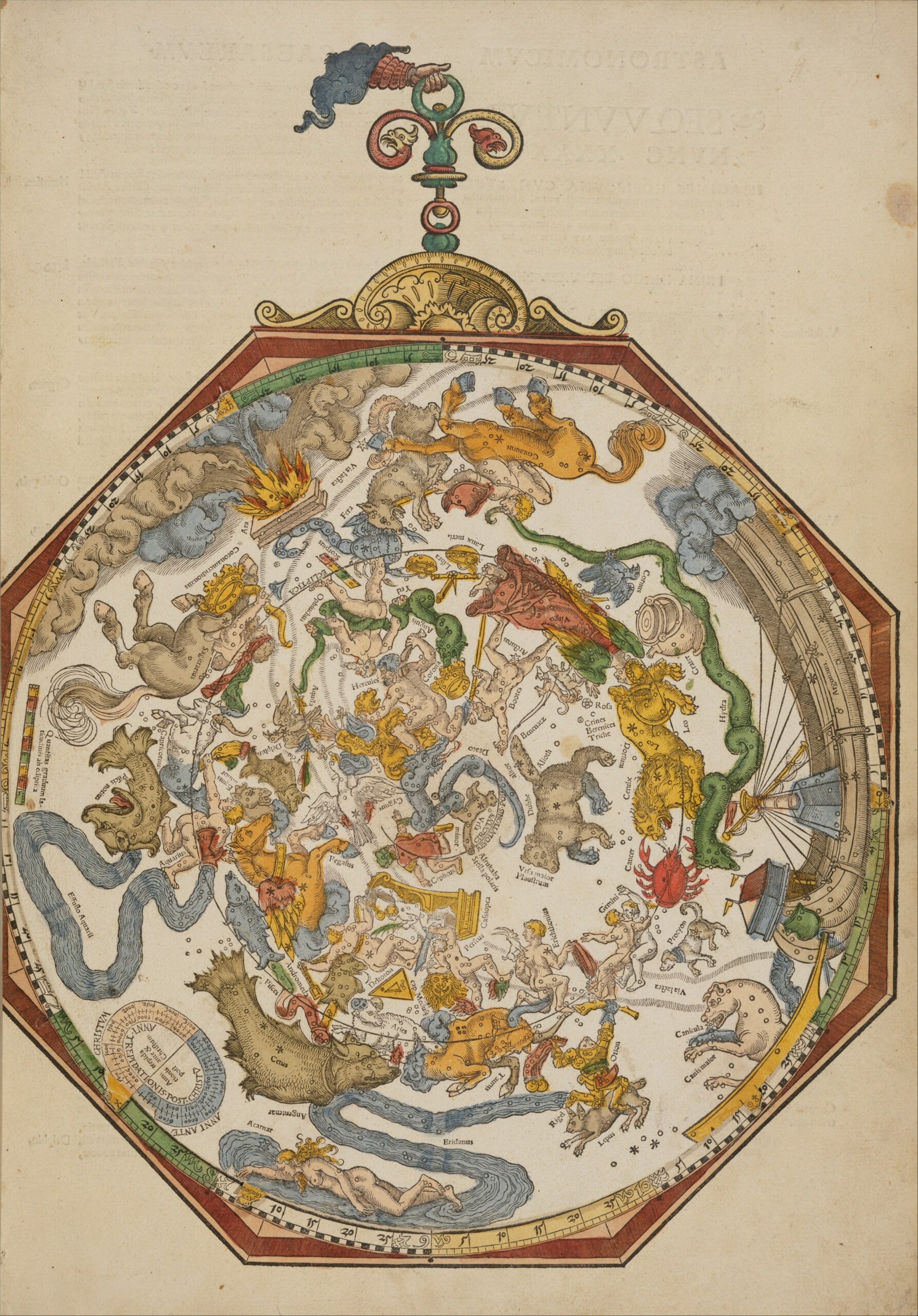

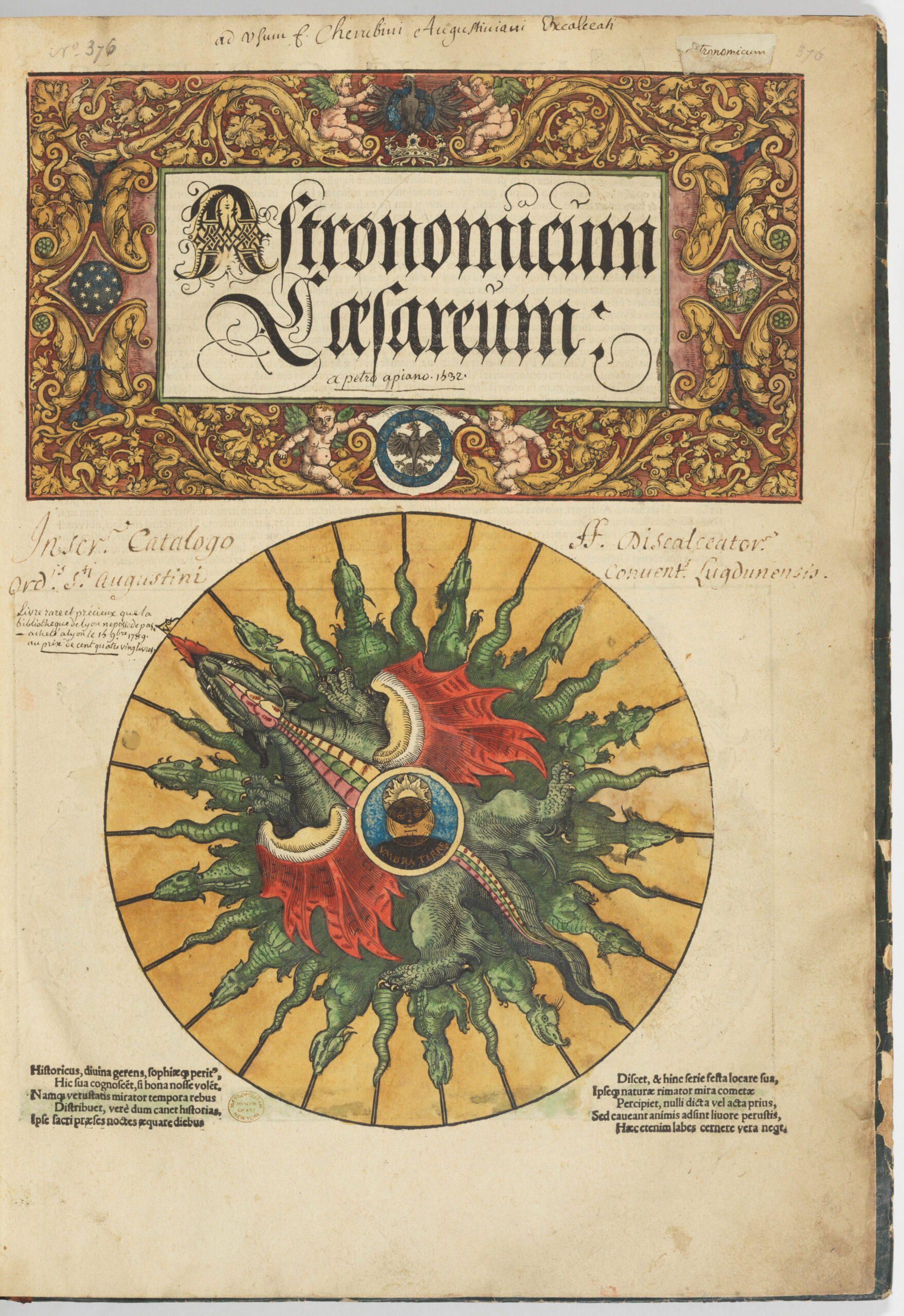

Art, science, and magic seem to have been rarely far apart during the Renaissance, as evidenced by the elaborate 1540 Astronomicum Caesareum — or “Emperor’s Astronomy” — seen here. “The most sumptuous of all Renaissance instructive manuals, ” the Metropolitan Museum of Art notes, the book was created over a period of 8 years by Petrus Apianus, also known as Apian, an astronomy professor at the University of Ingolstadt. Modern-day astronomer Owen Gingerich, professor emeritus at Harvard University, calls it “the most spectacular contribution of the book-maker’s art to sixteenth-century science.”

Apian’s book was mainly designed for what is now considered pseudoscience. “The main contemporary use of the book would have been to cast horoscopes,” Robert Batteridge writes at the National Library of Scotland. Apian used as examples the birthdays of his patrons: Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and his brother Ferdinand I. But the Astronomicum Caesareum did more than calculate the future.

Despite the fact that the geocentric model on which Apian based his system “would begin to be overtaken just 3 years after the book’s publication,” he accurately described five comets, including what would come to be called Halley’s Comet.

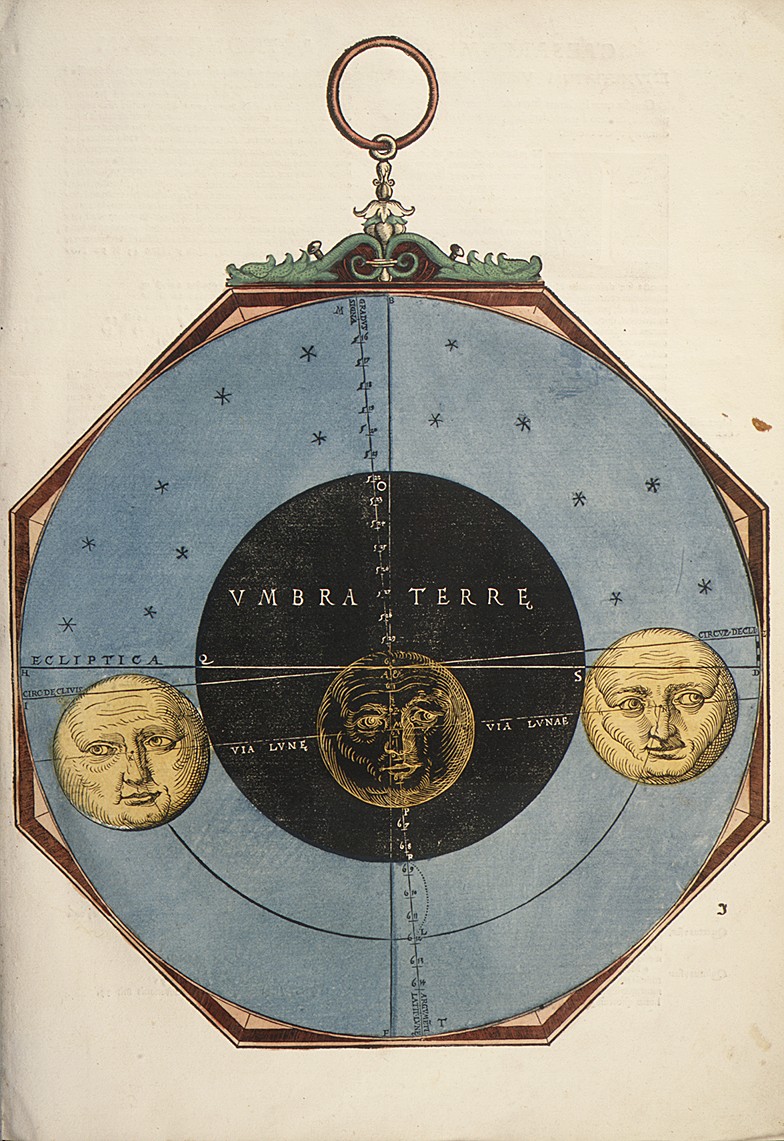

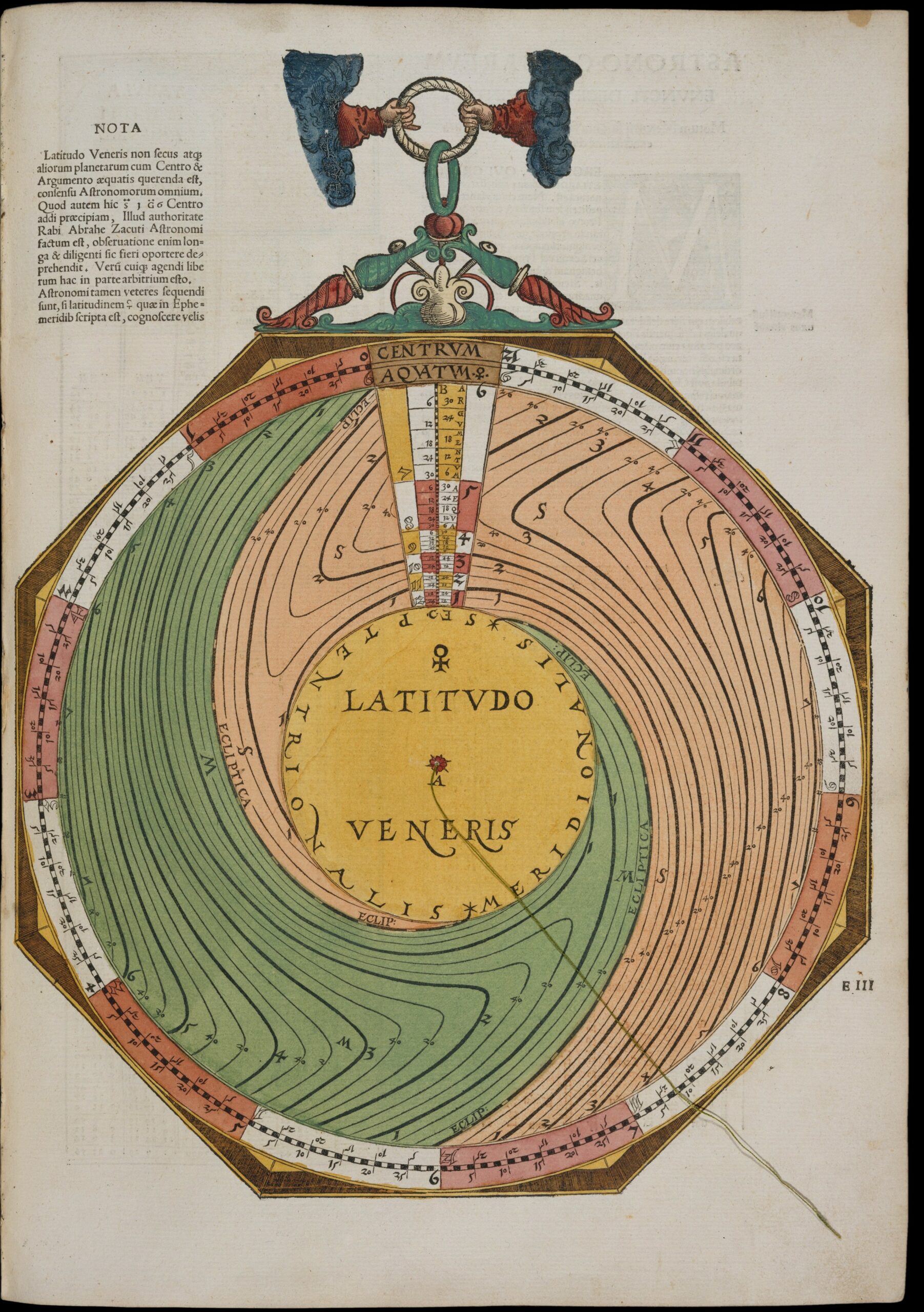

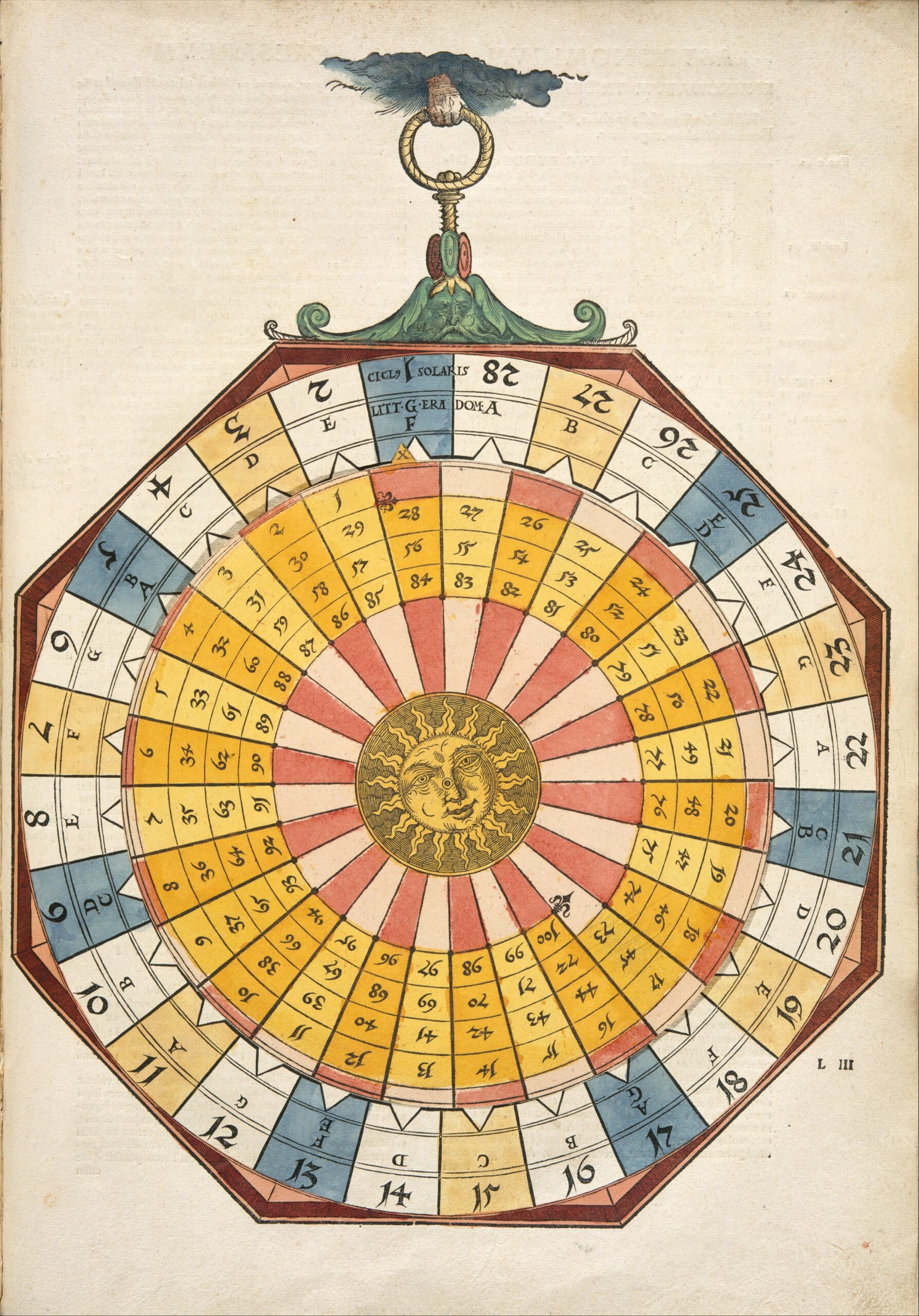

Apian also “observed that a comet’s tail always points away from the sun,” Fine Books and Collections writes, “a discovery for which he is credited.” He used his book “to calculate eclipses,” notes Gingerich in an introduction, including a partial lunar eclipse in the year of Charles’ birth. And, “in a pioneering use of astronomical chronology, he takes up the circumstances of several historical eclipses.” These discussions are accompanied by “several movable devices” called volvelles, designed “for an assortment of chronological and astrological inquiries.”

Medieval volvelles were first introduced by artist and writer Ramón Llull in 1274. A “cousin of the astrolabe,” Getty writes, the devices consist of “layered circles of parchment… held together at the center by a tie.” They were considered “a form of ‘artificial memory,’” called by Lund University’s Lars Gislén “a kind of paper computer.” Apian was a specialist of the form, publishing several books containing volvelles from his own Ingolstadt printing press. The Astronomicum Caesareum became the pinnacle of such scientific art, using its hand-colored paper devices to simulate the movements of the astrolabe. “The great volume grew and changed in the course of the printing,” Gingerich writes, “eventually comprising fifty-five leaves, of which twenty-one contain moving parts.”

Apian was rewarded handsomely for his work. “Emperor Charles V granted the professor a new coat of arms,” and “the right to appoint poets laureate and to pronounce as legitimate children born out of wedlock.” He was also appointed court mathematician, and copies of his extraordinary book lived on in the collections of European aristocrats for centuries, “a triumph of the printer’s art,” writes Gingerich, and an astronomy, and astrology, “fit for an emperor.”

Related Content:

A Medieval Book That Opens Six Different Ways, Revealing Six Different Books in One

160,000+ Medieval Manuscripts Online: Where to Find Them

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Behold the Astronomicum Caesareum, “Perhaps the Most Beautiful Scientific Book Ever Printed” (1540) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/34jHI4u

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment