John Steinbeck Wrote a Werewolf Novel, and His Estate Won’t Let the World Read It: The Story of Murder at Full Moon

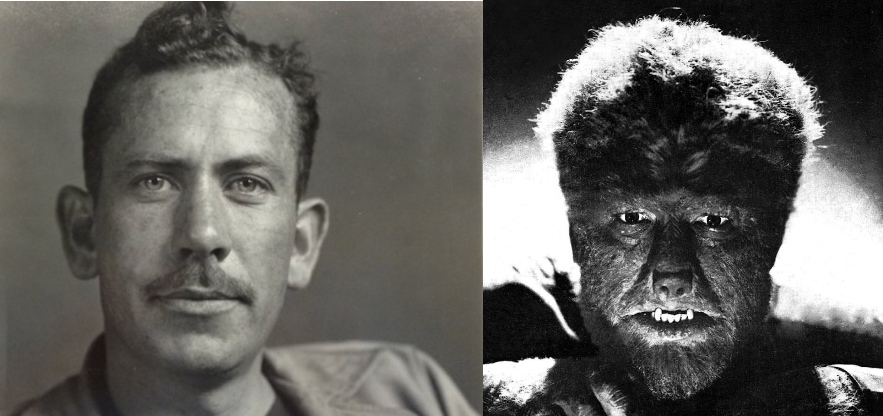

Photo of Steinbeck by Sonya Noskowiak, via Wikimedia Commons

John Steinbeck wrote Of Mice and Men, The Grapes of Wrath, and East of Eden, but not before he’d put a few less-acclaimed novels under his belt. He didn’t even break through to success of any kind until 1935’s Tortilla Flat, which later became a popular romantic-comedy film with Spencer Tracy and Hedy Lamarr. That was already Steinbeck’s fourth published novel, and he’d written nearly as many unpublished ones. Two of those three manuscripts he destroyed, but a fourth survives at the University of Texas in Austin’s Harry Ransom Center, which specialized in hoarding literary ephemera, especially from Nobel laureates. The unpublished novel deals not with laborers, farmers, or wastrels, but a werewolf.

“Set in a fictional Californian coastal town, Murder at Full Moon tells the story of a community gripped by fear after a series of gruesome murders takes place under a full moon,” writes The Guardian‘s Dalya Alberge. “Investigators fear that a supernatural monster has emerged from the nearby marshes. Its characters include a cub reporter, a mysterious man who runs a local gun club and an eccentric amateur sleuth who sets out to solve the crime using techniques based on his obsession with pulp detective fiction.”

Alberge quotes Stanford literary scholar Gavin Jones describing the book as related to Steinbeck’s “interest in violent human transformation – the kind of human-animal connection that you find all over his work; his interest in mob violence and how humans are capable of other states of being, including particularly violent murderers.”

Then still in his twenties, Steinbeck wrote Murder at Full Moon under the pseudonym Peter Pym. After receiving only rejections from publishers, he shelved the manuscript and seems not to have given it another thought, even in order to dispose of it. Though Steinbeck’s estate has declared its lack of interest in its posthumous publication, Jones believes it would find a receptive readership today: “It’s a horror potboiler, which is why I think readers would find it more interesting than a more typical Steinbeck.” It also “predicts Californian noir detective fiction. It is an unsettling story whose atmosphere is one of fog-bound, malicious, malignant secrecy.” It could at least have made quite a noir film, ideally one starring Lon Chaney, Jr., whose performance in Of Mice and Men proved he could play a Steinbeck character — to say nothing of his subsequent turn in The Wolf Man.

Related Content:

John Steinbeck’s Six Tips for the Aspiring Writer and His Nobel Prize Speech

John Steinbeck Reads Two Short Stories, “The Snake” and “Johnny Bear” in 1953

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

John Steinbeck Wrote a Werewolf Novel, and His Estate Won’t Let the World Read It: The Story of Murder at Full Moon is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2T8MAH7

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment