“The first great [economic] experiment was a ‘bad idea’ for the subjects, but not for the designers and local elites associated with them. This pattern continues until the present: placing profit over people.” — Noam Chomsky, Profit Over People

“A global decomposition is taking place. We call it the Fourth World War: neoliberalism’s globalization attempt to eliminate that multitude of people who are not useful to the powerful — the groups called ‘minorities’ in the mathematics of power, but who happen to be the majority population in the world.” — Subcomandante Marcos

Whether we think of global neoliberalism — to the extent that we think about it — as the inertia of centuries-old economic theory or as deliberate genocide, the effects are the same. The majority of the world’s population suffers under massive inequality, including, now, vaccine inequality, leading to raging COVID epidemics in some parts of the world as other places emerge from lockdowns and resume “normal” operations. The “Capitalist Hydra,” as Zapatista leader Subcomandante Marcos once called it, always seems to grow more heads.

Indeed, most plans to alleviate global poverty and disease seem to further enrich the architects and immiserate the targets of their purported care. Noam Chomsky has pointed out repeatedly that neoliberal economic rules are only applied to subject populations, since the wealthy ignore the strict conditions they impose by force and coercion on others, calling the outcomes a natural sorting of “winners and losers.” Ongoing global economic practices have accelerated a climate crisis that impacts the majority of the world’s (poor) population, sending millions on a collision course with brutality at the borders as they flee to other parts of the world for bare survival.

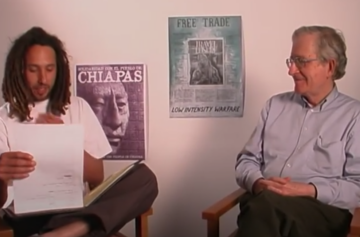

The multiple crises we now face were clearly evident at the turn of the millennium, when Rage Against the Machine played Mexico City for the first time in 1999. They released the concert footage in a video titled The Battle of Mexico City in 2001, the same year the indigenous guerrilla force EZLN — popularly known as the Zapatistas — marched on Mexico City. (Concert audio was released on vinyl this past June.) The video release included interviews with Chomsky and then-EZLN military leader Marcos, and you can see them both here.

At the top, Chomsky responds to a question about NAFTA, a “free-trade” agreement that proved his point about how such policies do the opposite of what they propose, benefitting the very few instead of the many. Chomsky, who analyzed the ways that the government and corporate media manufactured consent for their policies during the Vietnam War, wasn’t taken in by the hype. The agreement never had anything to do with free trade, he says, but with locking Mexico into programs of “structural adjustment” that kept people in poverty and the country dependent on economic terms dictated from outside its borders.

From the perspective of the indigenous people in Mexico fighting for an autonomous region in Chiapas, the struggle is not only against the Mexican government, but also an international economic order that imposes its will on the country and its citizens, who then turn on the poorest and most dispossessed among them in conditions of manufactured scarcity. Indigenous Mexicans, like other internally subjected people around the world, are deemed expendable, figured as a “problem” to be solved or eliminated. What is so striking about these perspectives, twenty years after the release of The Battle of Mexico City, is just how prescient, even prophetic, they sound today.

Related Content:

An Animated Introduction to Noam Chomsky’s Groundbreaking Linguistic Theories

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

When Rage Against the Machine Interviewed Noam Chomsky (1999) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3ilqie8

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment