His dark, dramatic works incorporate the kind of lighting we associate with horror films. Figures, twisted and contorted in tortuous poses, emerge from deep, black shadows. Instead of beatific smiles, his saints wear grimaces and furrowed frowns, as in The Denial of St. Peter, one of the few Caravaggios in the U.S., and a canvas depicting the weakest moment in the life of the Gospel character whose name means “the rock.” Caravaggio’s work came to be called tenebrism after the Latin for “dark or obscure,” for both its style and its substance.

There’s little evidence that Caravaggio (1571-1610) was a practitioner of the occult arts, but he was unafraid to look into the darkest realms of the human psyche, and to depict them on canvas. He was also drawn to artist’s models who looked weathered and worn down by life, and his hyper-realistic Biblical scenes scandalized many people and thrilled more, and made him the most famous painter in Rome, for a time.

Caravaggio himself was a scandalous character who brawled and fornicated his way through Rome, then in exile in Naples, where he died an early death at age 38, from either an unspecified fever or lead poisoning. (A new film by Italian actor and director Michele Placido imagines Caravaggio in 1600, “a brilliant and subversive artist who lives with the burden of a death sentence. The shadow of a merciless, occult power is about to loom over him.”)

He left no writing behind, the details of his life are sketchy at best, and he fell into obscurity for many years after his death, but not before his paintings showed the way forward for Baroque painters who followed him as Caravaggisti or tenebrosi (“shadowists”), including such great masters as Peter Paul Rubins and Rembrandt. So, how did he do it? How did Caravaggio invent modern painting, as some critics have claimed?

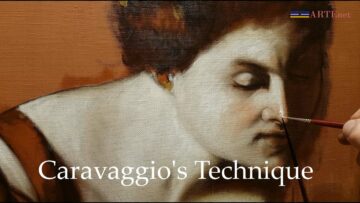

“The testimonies of his contemporaries are scarce and imprecise regarding the procedure he adopted to complete his work,” notes the Artenet video above, an exploration of Caravaggio’s technique. We do know a few details: he worked from models, who held the acrobatic poses in his paintings while he worked; he had a studio in which light streamed in from above; and he worked quickly — “He could paint up to three heads in a single day.”

The lack of unfinished work by Caravaggio has made it difficult to trace his process backward, but some evidence remains. See Caravaggio’s “entire pictorial process” recreated, and learn how a painter called “the master of light” made his luminous figures by surrounding them with darkness.

Related Content:

A Short Introduction to Caravaggio, the Master Of Light

Living Paintings: 13 Caravaggio Works of Art Performed by Real-Life Actors

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

How Caravaggio Painted: A Re-Creation of the Great Master’s Process is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3xrzwMg

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment