A Billion Years of Tectonic-Plate Movement in 40 Seconds: A Quick Glimpse of How Our World Took Shape

We all remember learning about tectonic plates in our school science classes. Or at least we do if we went to school in the 1960s or later, that being when the theory of plate tectonics — which holds, broadly speaking, that the Earth’s surface comprises slowly moving slabs of rock — gained wide acceptance. But most everyone alive today will have been taught about Pangea. An implication of Alfred Wegener’s theory of “continental drift,” first proposed in the 1910s, that the single gigantic landmass once dominated the planet.

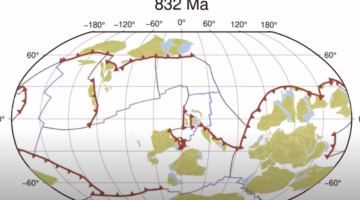

Despite its renown, however, Pangea makes only a brief appearance in the animation of Earth’s history above. Geological scientists now categorize it as just one of several “supercontinents” that plate tectonics has gathered together and broken up over hundreds and hundreds of millennia. Others include Kenorland, in existence about 2.6 billion years ago, and Rodinia, 900 million years ago; Pangea, the most recent of the bunch, came apart around 175 million years ago. You can see the process in action in the video, which compresses a billion years of geological history into a mere 40 seconds.

At the speed of 25 million years per second, and with outlines drawn in, the movement of Earth’s tectonic plates becomes clearly understandable — more so, perhaps, than you found it back in school. “On a human timescale, things move in centimeters per year, but as we can see from the animation, the continents have been everywhere in time,” as Michael Tetley, co-author of the paper “Extending full-plate tectonic models into deep time,” put it to Euronews. Antarctica, which “we see as a cold, icy inhospitable place today, actually was once quite a nice holiday destination at the equator.”

Climate-change trends suggest that we could be vacationing in Antarctica again before long — a troubling development in other ways, of course, not least because it underscores the impermanence of Earth’s current arrangement, the one we know so well. “Our planet is unique in the way that it hosts life,” says Dietmar Müller, another of the paper’s authors. “But this is only possible because geological processes, like plate tectonics, provide a planetary life-support system.” Earth won’t always look like it does today, in other words, but it’s thanks to the fact that it doesn’t look like it did a billion years ago that we happen to be here, able to study it at all.

Related Content:

A Map Shows Where Today’s Countries Would Be Located on Pangea

What Earth Will Look Like 100 Million Years from Now

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

A Billion Years of Tectonic-Plate Movement in 40 Seconds: A Quick Glimpse of How Our World Took Shape is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3yPhHae

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment