Explore Divine Comedy Digital, a New Digital Database That Collects Seven Centuries of Art Inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy

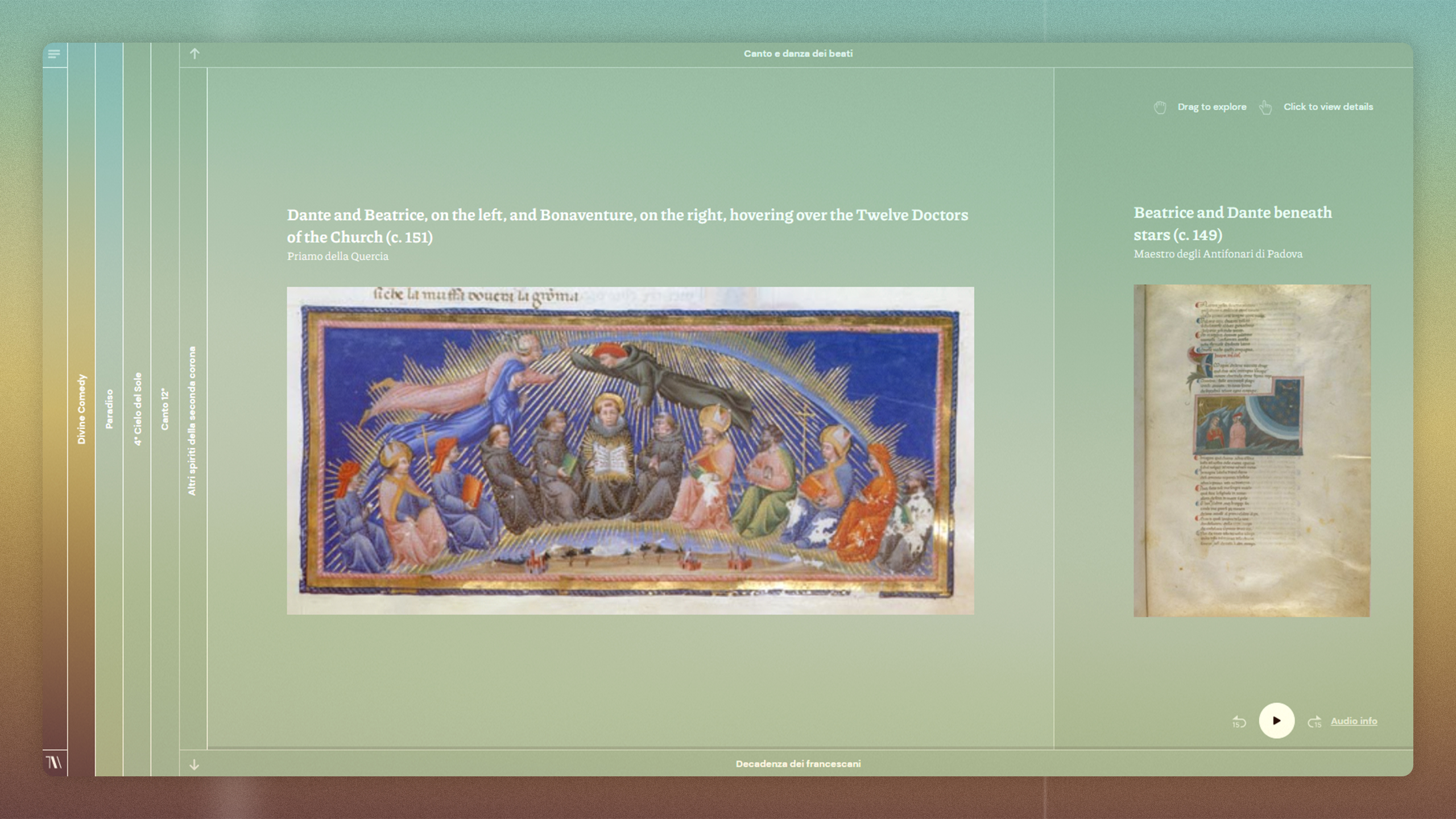

The number of artworks inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy in the seven hundred years since the poet completed his epic, vernacular masterwork is so vast that referring to the poem inevitably means referring to its illustrations. These began appearing decades after the poet’s death, and they have not stopped appearing since. Indeed, it might be fair to say that the title Divine Comedy (simply called Comedy before 1555) names not only an epic poem but also its many constellations of artworks and interpretations, which would have filled a modest-sized set of Dante encyclopedias before the internet.

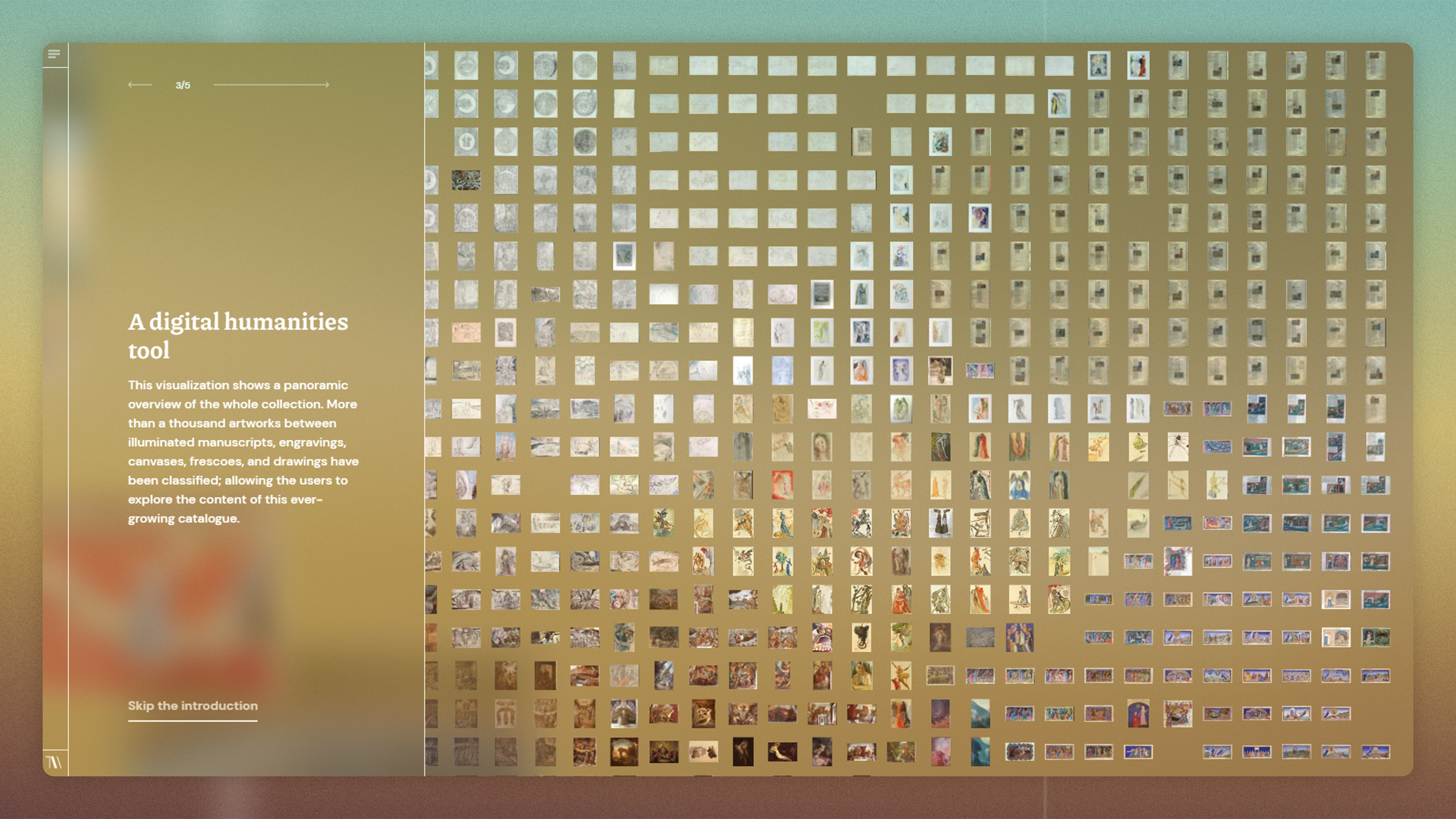

Luckily for art historians and Dante scholars and historians working today, there is now Divine Comedy Digital, a beautifully designed database which brings these artworks — spread out all over the world — together in one virtual place.

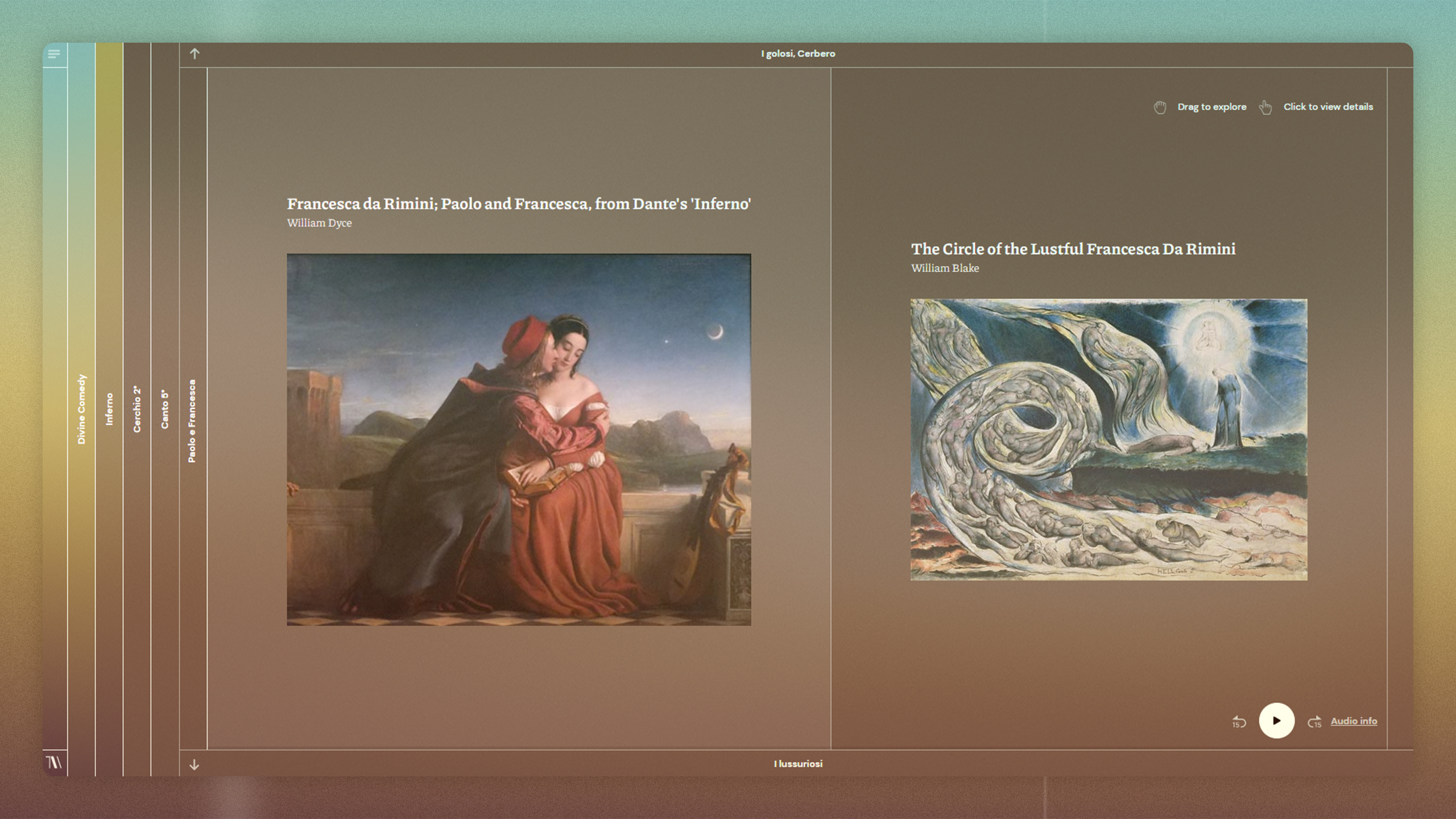

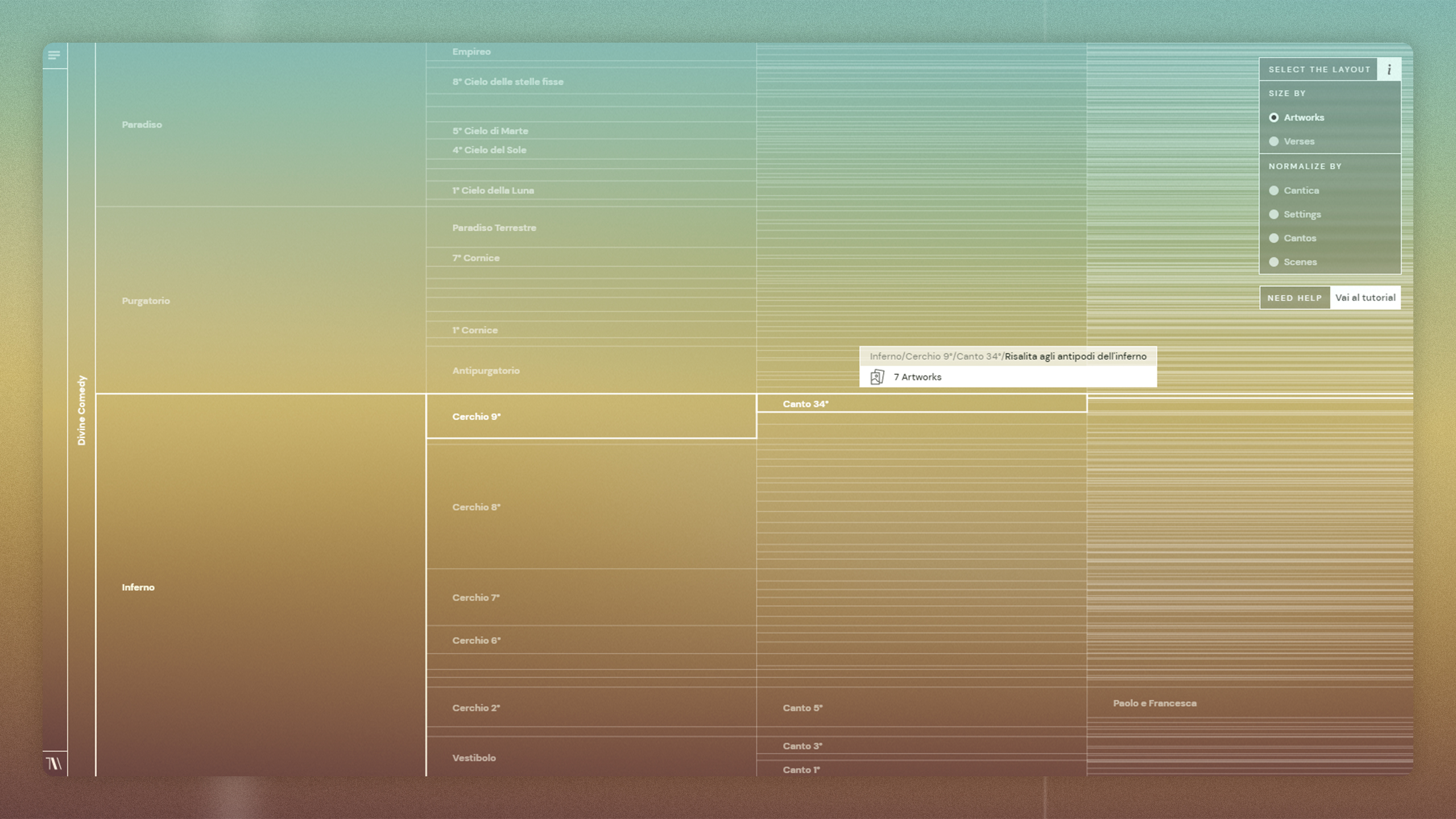

The interface requires no special Dante knowledge to navigate, though it helps to be familiar with the poem and/or have a reference copy nearby when looking through the menus. Dividing neatly into the poem’s three books (or cantiche), the menu at the left further breaks down into circles (Inferno), terraces (Purgatorio), and Cantos (all three books).

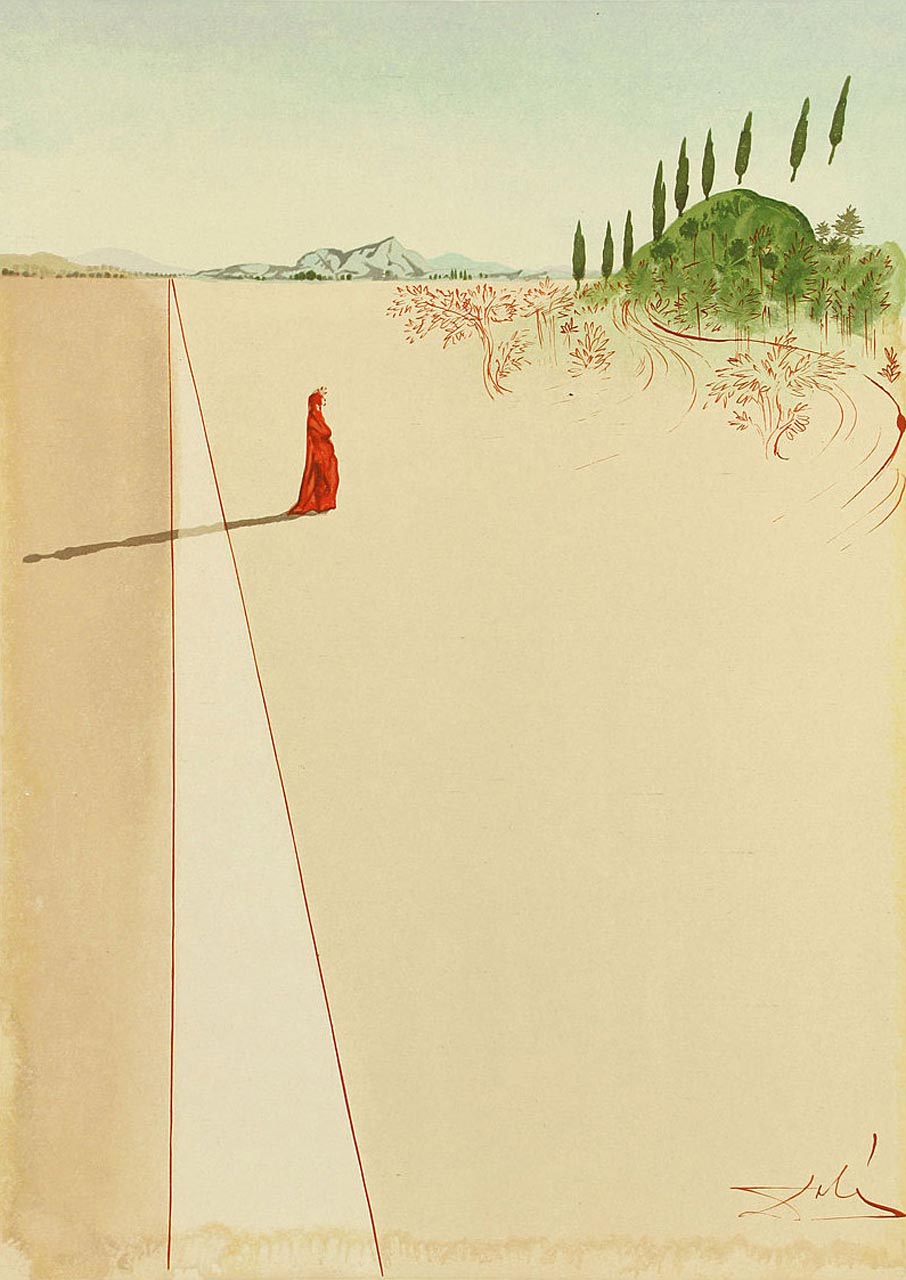

Toggling between options in a menu on the right allows visitors to see the number of illustrated verses in each Canto or the number of artworks. Within a matter of minutes, you’ll be discovering Dante illustrations you never knew existed, from Salvador Dali’s The Delightful Mount (1950, above) to Alessandro Vellutello’s Dante and St. Bernard, Mary and the Trinity (1544) and hundreds of others in the years in-between.

Calling itself a “slow surfing site,” Divine Comedy Digital contains a handy tutorial if you do get lost and allows users “not only to navigate through the collection, but also to suggest missing artworks.” So far, the 17th and 18th centuries are hugely underrepresented, though not for a lack of Dante-inspired artwork made in that two-hundred year period. The gaps mean there is much more Dante art to come.

Released in June of this year, the project is the work of The Visual Agency, “an information design agency specialized in data-visualization based in Milan and Dubai” and was created to celebrate the 700th anniversary of Dante’s death. As he continues to inspire artists for the next few hundred years, perhaps the work based on his epic poem will trend more digital than medieval, creating interpretations the poet never could have dreamt. Enter the Divine Comedy Digital project here.

You can also see some of the earliest illustrated editions of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1487-1568), courtesy of Columbia University, here.

Related Content:

A Free Course on Dante’s Divine Comedy from Yale University

Mœbius Illustrates Dante’s Paradiso

Artists Illustrate Dante’s Divine Comedy Through the Ages: Doré, Blake, Botticelli, Mœbius & More

Visualizing Dante’s Hell: See Maps & Drawings of Dante’s Inferno from the Renaissance Through Today

Hear Dante’s Inferno Read Aloud by Influential Poet & Translator John Ciardi (1954)

A Digital Archive of the Earliest Illustrated Editions of Dante’s Divine Comedy (1487-1568)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Explore Divine Comedy Digital, a New Digital Database That Collects Seven Centuries of Art Inspired by Dante’s Divine Comedy is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2Uvrq76

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment