Thirty or so Christmases ago, I received my first skateboard. Alas, it was also my last skateboard: not long after I got the hang of balancing on the thing, it was run over and snapped in half by a mail truck. There went my last chance at Olympic athleticism, though I couldn’t have known it at the time: it debuted as an event at the Summer Olympics just this year, and its competitions are underway even now in Tokyo. This is, in any case, a bit late for me, given the relative… maturity of my years as against those of the average Olympic skateboarder. But then, Tony Hawk is in his fifties, and something tells me he could still show those kids a thing or two.

Hawk, the most famous skateboarder in the world, shows us 21 things in the Wired video above— specifically, 21 skateboarding moves, each one representative of a higher difficulty level than the last. At level one, we have the “flat-ground ollie,” which involves “using one foot to snap the tail of the board downward, and then you have the board sort of aiming up, and then sliding your front foot at the right time in order to bring that board up and level it out in the air.”

To the untrained eye, a well-executed ollie projects the image of skater and board are “jumping” as a whole. But it can only be mastered by those willing to keep their feet on the board, rather than obeying the instinct to put one foot off to the side. “People do that for years,” laments Hawk.

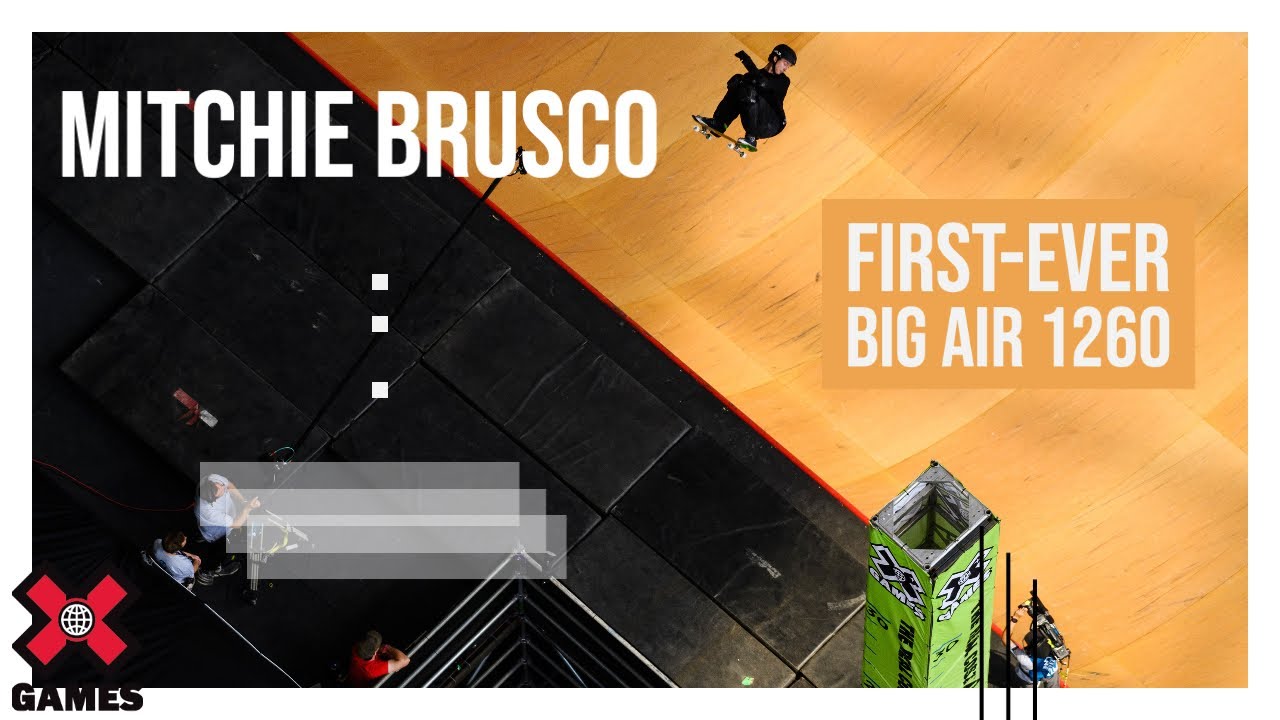

Level ten finds Hawk on the half-pipe doing a “360 aerial.” He describes the action as we watch him perform it: “I’m going up the ramp, I’m turning in the frontside direction a full 360, and I’m coming down backwards” — but not yet flipping the board while in the air, a slightly more advanced move. The final levels enter “the realm of unreality,” covering the NBD (Never Been Done) tricks that skaters nevertheless believe possible. For Level 21 he chooses the “1260 spin” — “three and a half rotations” — which he’s never even seen attempted. Or at least he hadn’t at the time of this video’s shoot in 2019; Mitchie Brusco landed one at the X Games just two days later. Even now, given the seemingly infinite potential variations of and expansions on every trick, skateboarding is unlikely to have hit its physical limits. Just imagine what the kids who successfully dodge their mailman now will be able to pull off when they grow up.

Related Content:

Werner Herzog Discovers the Ecstasy of Skateboarding: “That’s Kind of My People”

The Piano Played with 16 Increasing Levels of Complexity: From Easy to Very Complex

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Tony Hawk Breaks Down Skateboarding Into 21 Levels of Difficulty: From Easy to Complex is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2VkJRM8

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment