Only the violence and duration of your hardened dream can resist the hideous mechanical civilization that is your enemy, that is also the enemy of the ‘..pleasure-..principle’ of all men. It is man’s right to love women with the ecstatic heads of fish. — Salvador Dalí, “Declaration of the Independence of the Imagination and the Rights of Man to His Own Madness”

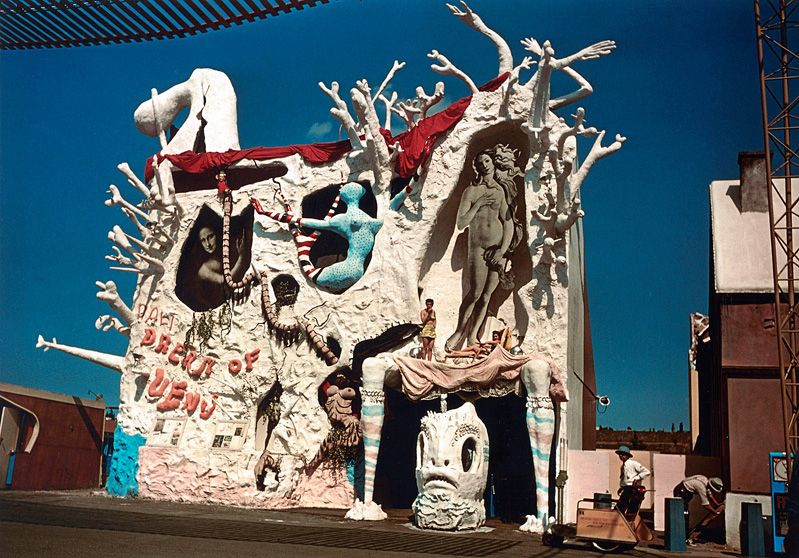

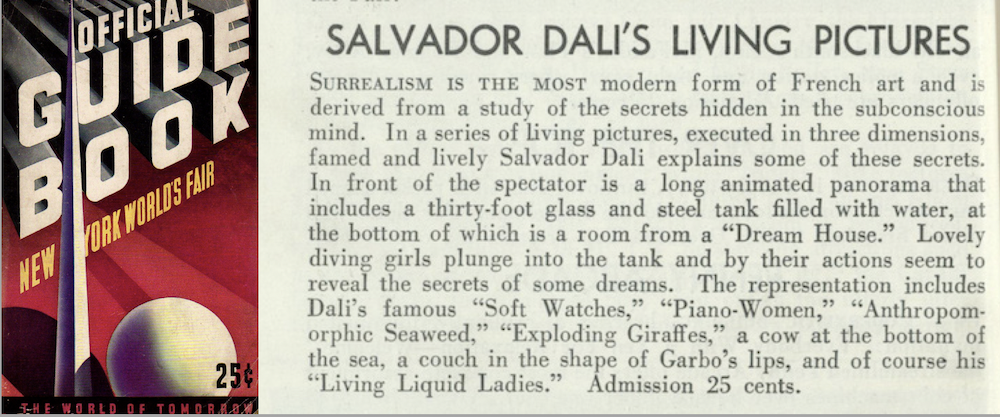

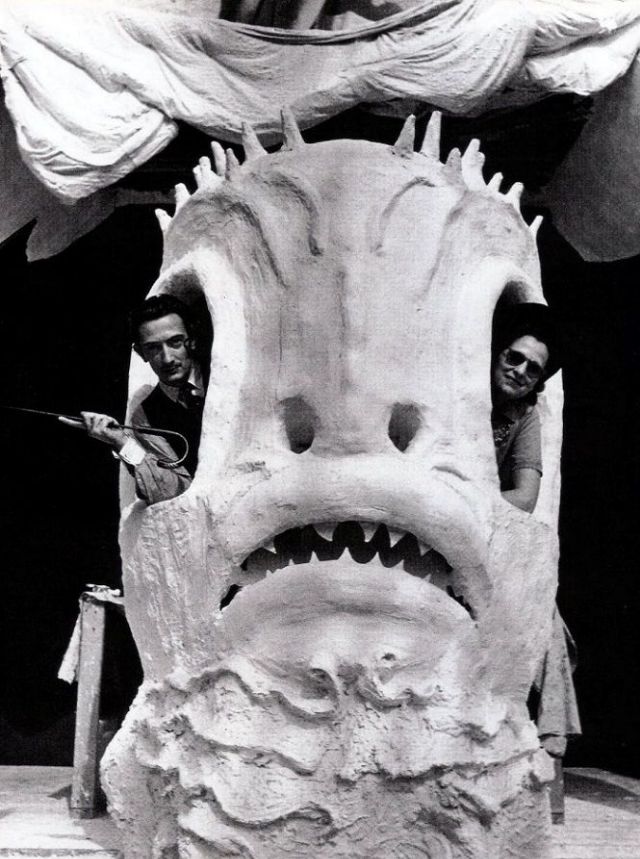

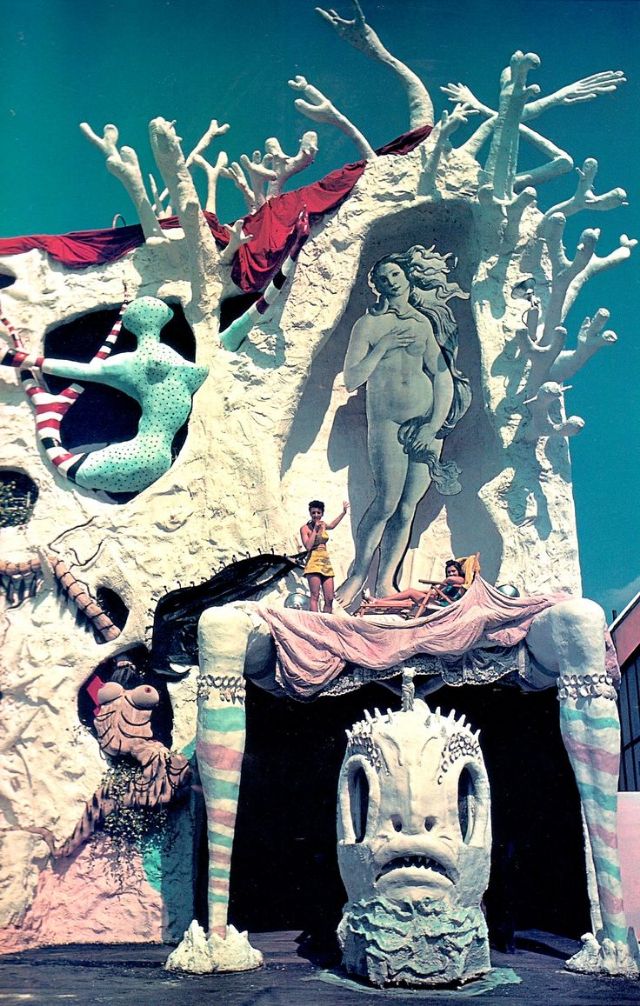

Whatever organizers of the 1939 New York World’s Fair thought they might get when Salvador Dalí was chosen to design a pavilion, they got a Coney Island of the Surrealist mind. The vision was so initially upsetting, the committee felt compelled to censor Dalí’s plans. They nixed the idea, for example, of reproducing a gigantic reproduction of Boticelli’s Venus with a fish head — as well as fish heads for the many partially nude models in Dalí’s exhibit. These and other changes enraged the artist, and he hired a pilot to drop a manifesto over the city in which he declared “the Independence of the Imagination and the Rights of Man to His Own Madness.”

It was all part of the theater of the “Dream of Venus,” Dalí’s so-called “funhouse” and public experiment playing with “the old polarity between the elite and popular cultures,” says Montse Aguer, Director of the Dalí Museums.

This conflict had “changed into a tense confrontation between true art and mass culture, with all that the second ambiguous concept brought with it consumed by the masses, but not produced by them.” While Dalí rained down a “screw you” letter to the establishment, he also seduced the public away from “the streamline style that dominated the Expo in 1939″ — the “modern architecture, which with time had turned against modern life.”

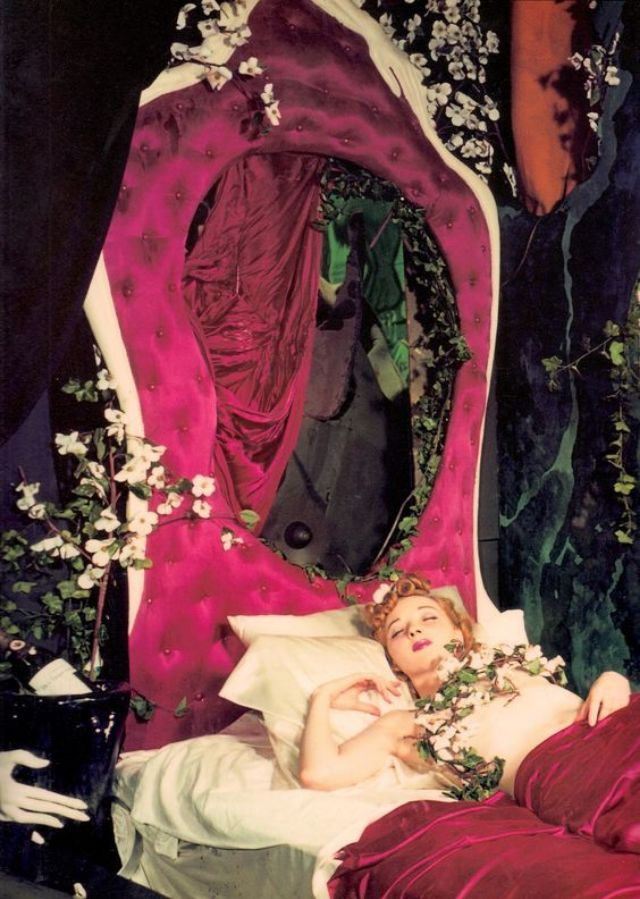

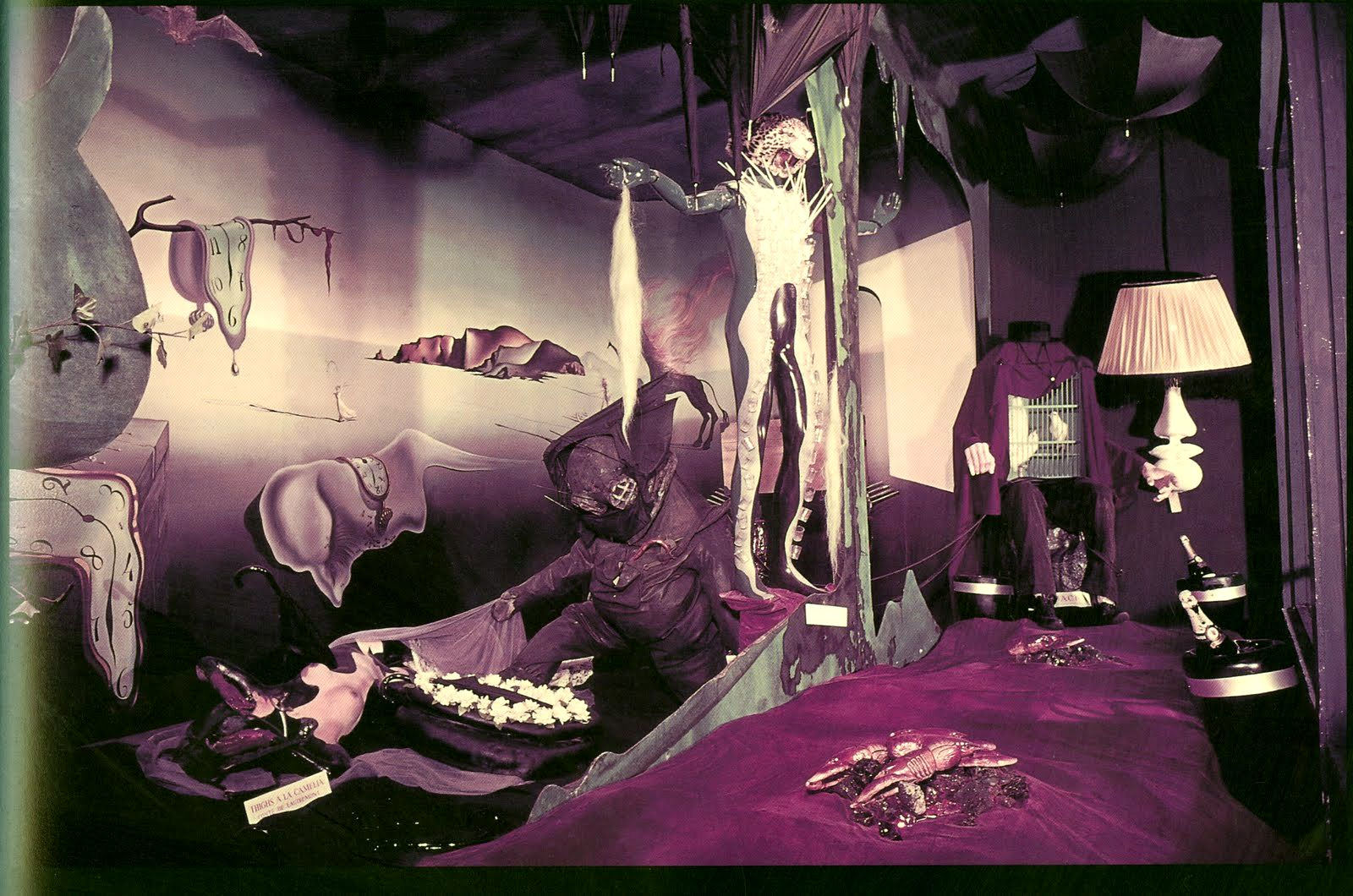

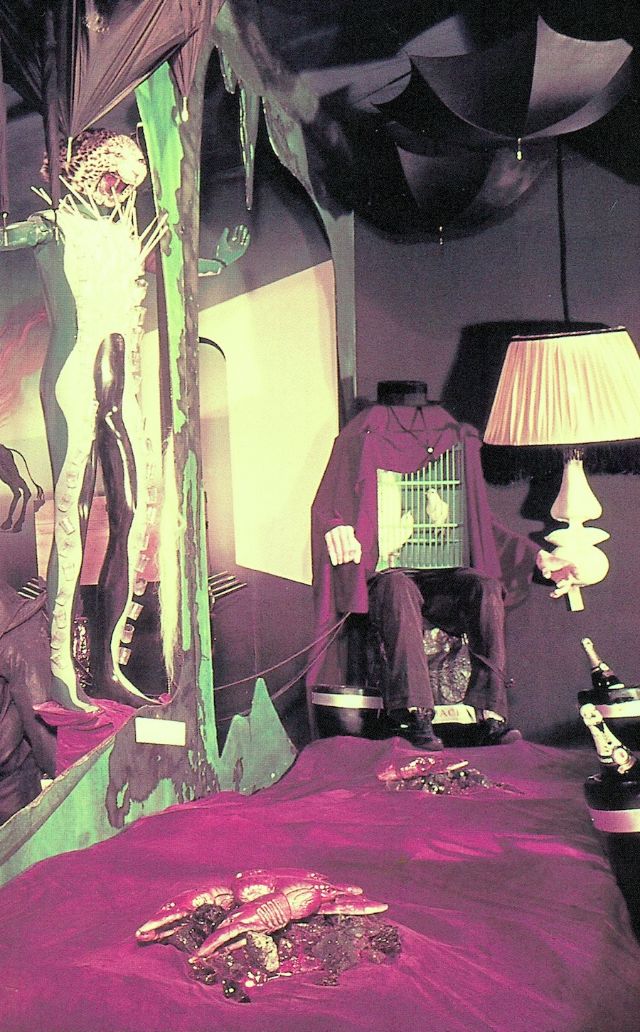

Rather than a sleek “World of Tomorrow,” visitors to Dalí’s pavilion encountered “a kind of shapeless mountain from which sprouts out, like the body of a sticky hedgehog, a series of soft appendages, some in the shape of arms and hand; others of cactus or tips and others of crutches…. The world of machines, cars and robots had been replaced — or should one say challenged — by a universe of dreams.” Inside the weird structure, a goddess stretched out on bed, dreaming two dreams, “wet,” and “dry.” As Dangerous Minds describes it, once visitors entered the exhibit, through a giant pair of legs, they encountered:

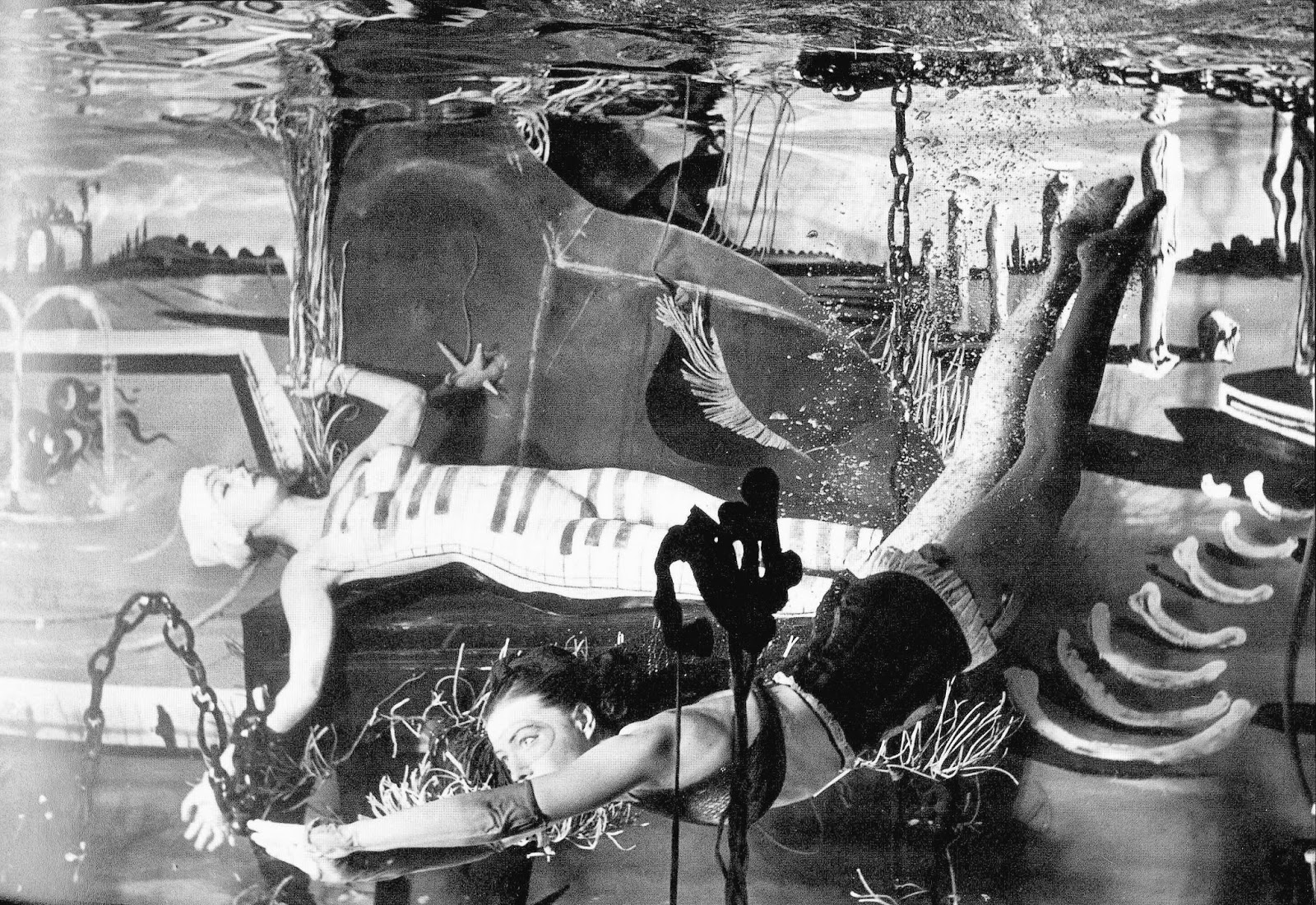

Two huge swimming pools featured partially nude models floating around in the water. In one of the pools, a woman dressed in a head-to-toe rubber suit that had been painted with piano keys cavorted around with other “mermaids” who “played” her imaginary piano. In fact, the place was filled with scantly-clad women lying in beds or perched on top of a taxi being driven by a female looking S&M batwoman. There were functional telephones made of rubber as well as an offputting life-size version of a cow’s udder that you could touch—if you wanted to, that is.

The exhibition had been coordinated by architect, artist, and collector Ian Woodner and New York art dealer Julien Levy. It was so popular “it reopened for a second season,” notes Messy Nessy, “but once torn down it faded from memory and its outlandishness became the stuff of urban myth.” In 2002, the photographs here by German-born photographer Eric Schaal were rediscovered and collected in a book titled Salvador Dalí’s Dream of Venus: The Surrealist Funhouse from the 1939 World’s Fair. See rare footage from the pavilion in the short documentary at the top and read Dalí’s manifesto here.

Related Content:

Salvador Dalí Explains Why He Was a “Bad Painter” and Contributed “Nothing” to Art (1986)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

When Salvador Dalí Created a Surrealist Funhouse at New York World’s Fair (1939) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3g7uldf

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment