The Acoustics of Stonehenge: Researchers Build a Model to Understand How Sound Reverberated within the Ancient Structure

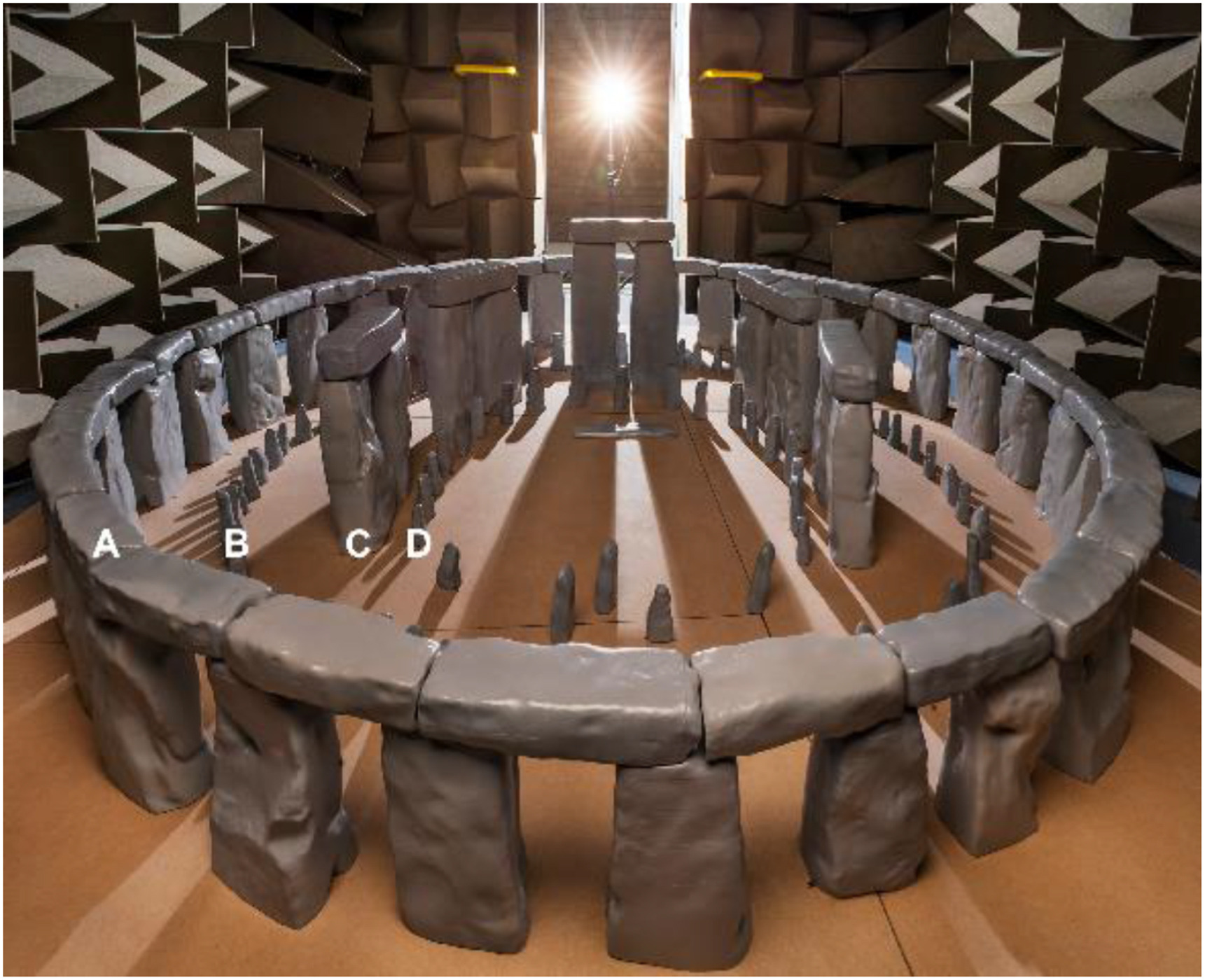

It’s impossible to resist a Spinal Tap joke, but the creators of the complete scale model of England’s ancient Druidic structure pictured above had serious intentions — to understand what those inside the circle heard when the stones all stood in their upright “henge” position. A research team led by acoustical engineer Trevor Cox constructed the model at one-twelfth the actual size of Stonehenge, the “largest possible scale replica that could fit inside an acoustic chamber at the University of Salford in England, where Cox works,” reports Bruce Bower at Science News. The tallest of the stones is only two feet high.

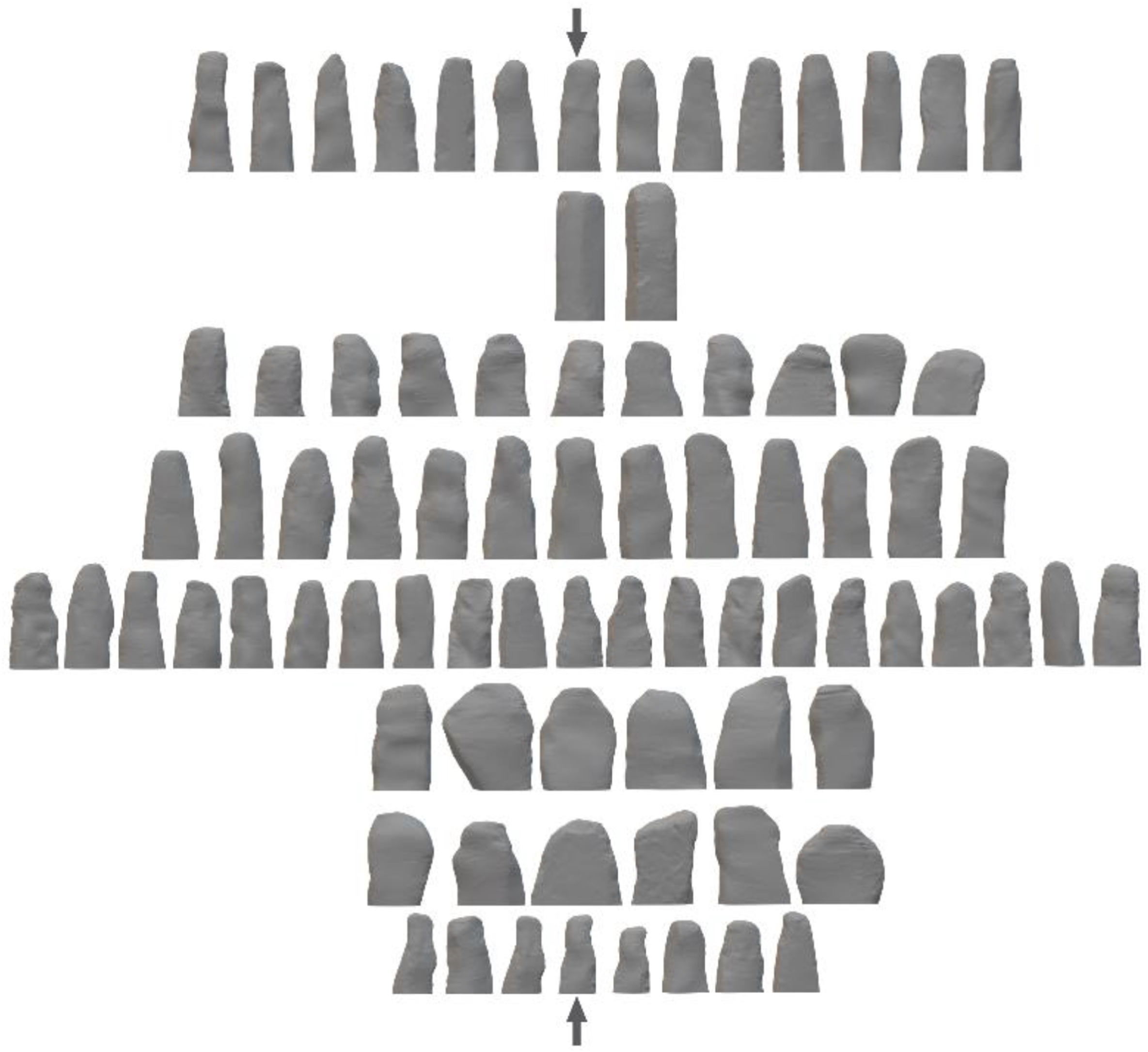

This is not the first time acoustic research has been carried out on Stonehenge, but previous projects were “all based on what’s there now,” says Cox. “I wanted to know how it sounded in 2200 B.C., when all the stones were in place.” The experiment required a lot of extrapolation from what remains. The construction of “Stonehenge Lego” or “Minihenge,” as the researchers call it, assumes that “Stonehenge’s outer circle of standing sarsen stones — a type of silcrete rock found in southern England — had originally consisted of 30 stones.” Today, there are 17 sarsen stones in the outer circle among the 63 complete stones remaining.

“Based on an estimated total 157 stones placed at the site around 4,200 years ago, the researchers 3-D printed 27 stones of all sizes and shapes,” Bower explains. “Then, the team used silicone molds of those items and plaster mixed with other materials to re-create the remaining 130 stones. Simulated stones were constructed to minimize sound absorption, much like actual stones at Stonehenge.” Once Cox and his team had the model completed and placed in the acoustic chamber, they began experimenting with sound waves and microphones, measuring impulse responses and frequency curves.

What were the results of this sonic Stonehenge recreation? “We expected to lose a lot of sound vertically, because there’s no roof,” says Cox. Instead, researchers found “thousands upon thousands of reflections as the sound waves bounced around horizontally.” Participants in ritual chants or musical celebrations inside the circle would have heard the sound amplified and clarified, like singing in a tiled bathroom. For those standing outside the monument, or even within the outer circle of stones, the sound would have been muffled or dampened. Likewise, the arrangement would have dampened sound entering the inner circle from outside.

Indeed, the effect was so pronounced that “the placement of the stones was capable of amplifying the human voice by more than four decibels, but produced no echoes,” notes Artnet. This suggests that the site’s acoustic properties were not accidental, but designed as part of its essential function for an elite group of participants, “even though the site’s construction would have required a huge amount of manpower.” This is hardly different from other monumental ancient religious structures like pyramids and ziggurats, built for royalty and an elite priesthood. But it’s only one interpretation of the structure’s purpose.

While Cox and his team do not believe acoustics were the primary motivation for Stonehenge’s design — astrological alignment seems to have been far more important — it clearly played some role. Other scholars have their own hypotheses. Research still needs to account for environmental factors — or why “Stonehenge hums when the wind blows hard,” as musicologist Rupert Till points out. Some have speculated the stones may have been instruments, played like a giant xylophone, a theory tested in a 2013 study conducted by researchers from the Royal College of Art, but this, too, remains speculative.

As the great Stonehenge enthusiast Nigel Tufnel once sang, “No one knows who they were, or what they were doing.” But whatever it sounded like, Cox and his colleagues have shown that the best seats were inside the inner circle. Read the research team’s full article here.

Related Content:

The Ancient Astronomy of Stonehenge Decoded

An Artist Visits Stonehenge in 1573 and Paints a Charming Watercolor Painting of the Ancient Ruins

The Spinal Tap Stonehenge Debacle

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The Acoustics of Stonehenge: Researchers Build a Model to Understand How Sound Reverberated within the Ancient Structure is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3A8AyOY

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment