How many architectural careers have been kindled by Lincoln Logs? Since their invention in the mid-1910s, these deceptively simple wooden building blocks have entertained generations of children, whichever profession they entered upon growing up. I myself have fond memories of playing with Lincoln Logs, which, with about 70 years of history already behind them, were a venerable playtime institution, not that I knew it at the time. I certainly had no idea that they’d been invented by the son of Frank Lloyd Wright — nor, indeed, did I have any idea who Frank Lloyd Wright was. I just knew, as many kids did before me and many do still today, that they were fun to stack up into cabins, or at least cabin-like shapes.

This enduring toy’s full origin story is told in the Decades TV video above. When Wright designed his own family home in Oak Park, Illinois, he included a custom playroom for his six children. Its stock of innovative toys included “geometric building blocks developed by Friedrich Froebel, the German educator who came up with the concept of kindergarten.”

The special fascination for these blocks exhibited by Wright’s second son John Lloyd Wright hinted at a conflict of interests to come: though John “began to feel that spirit of being an architect” in the playroom, says toy historian Steven Sommers, “there was always a tension between his father, who was an architect, and his [own] love for building toys that he’d begun to learn in that Froebel system of early childhood education.” The two intersected when Wright fils assisted Wright père on one of the latter’s most famous works, the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo.

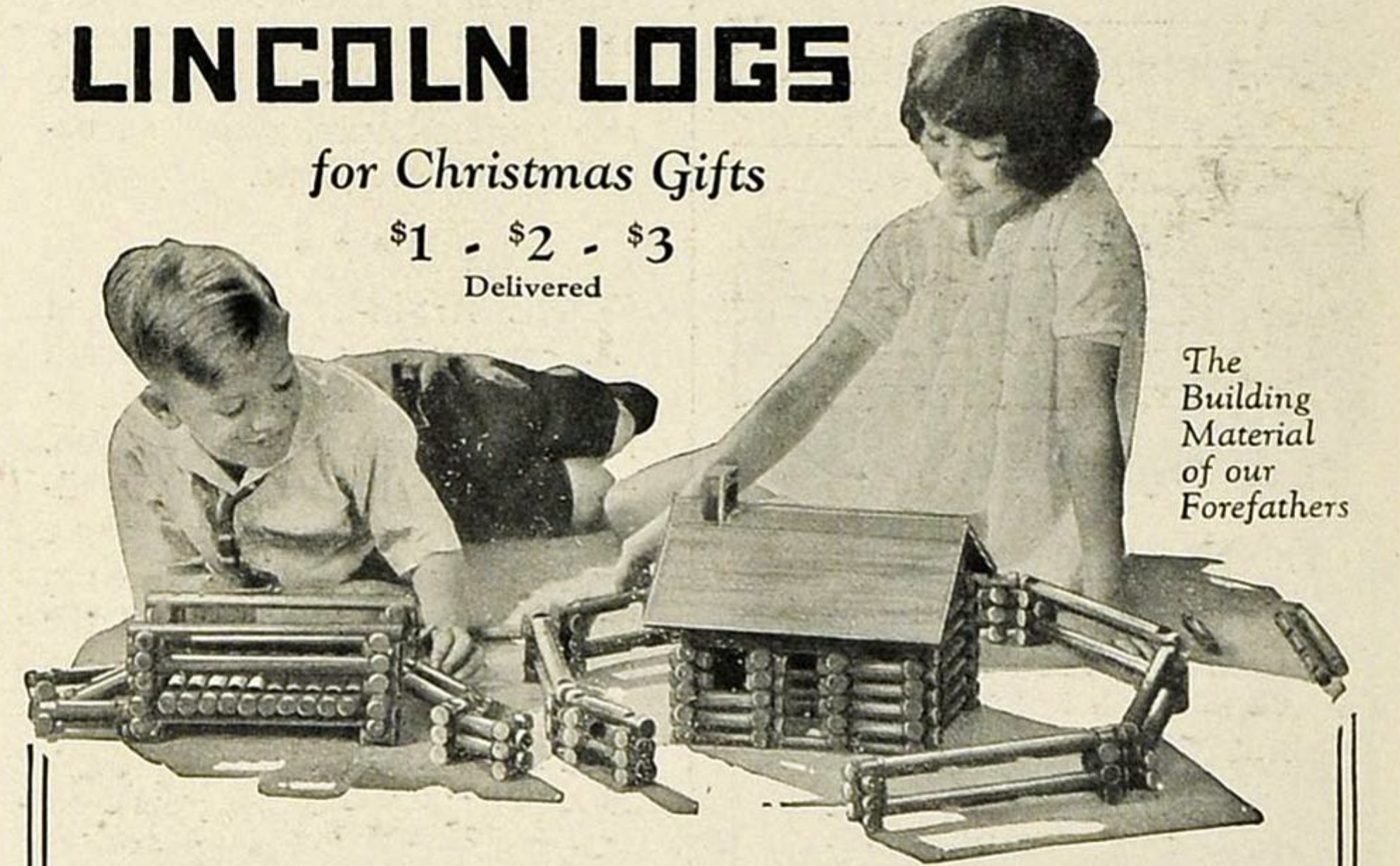

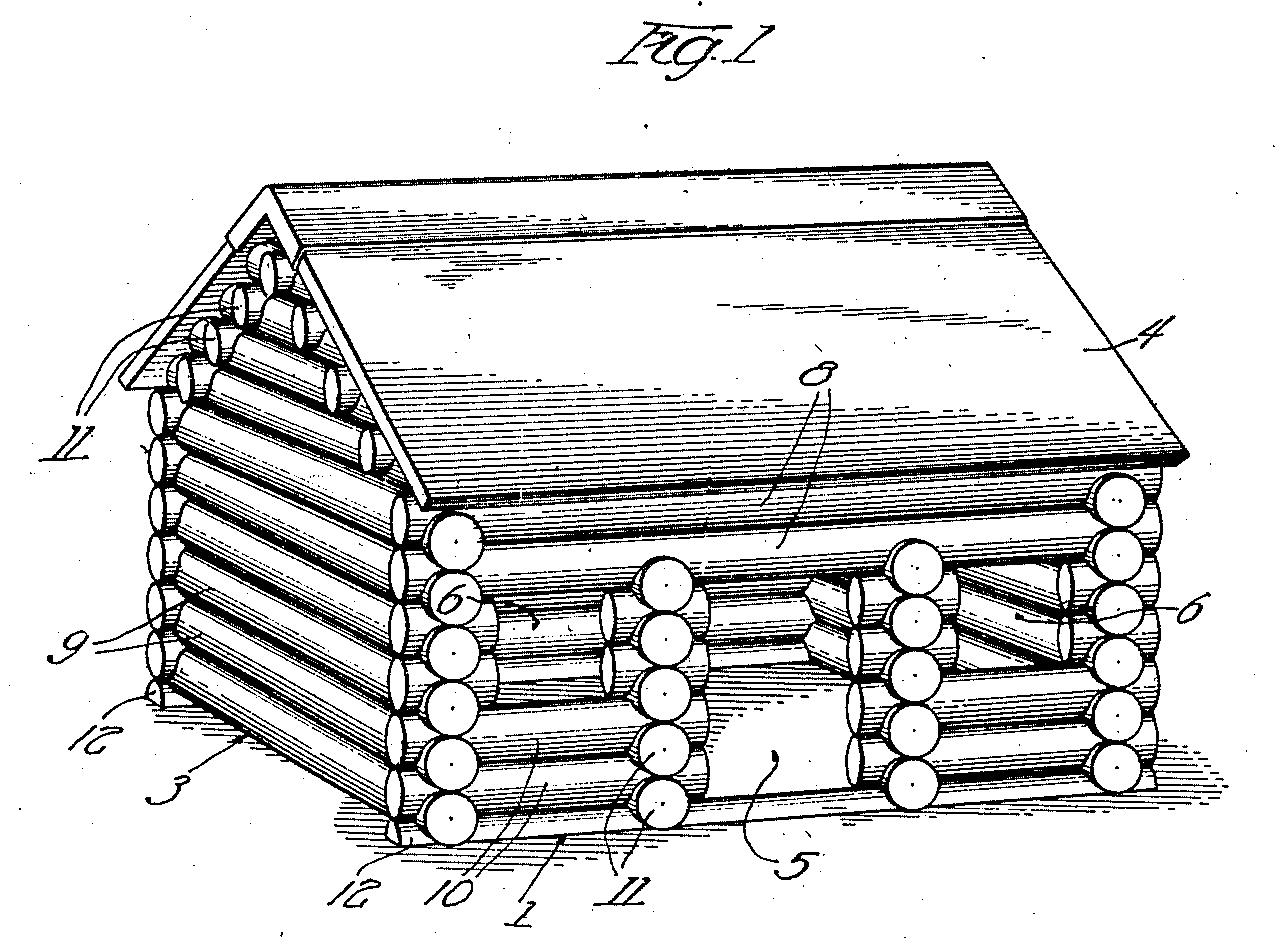

John Lloyd Wright took note of the interlocking timber beams used to make the structure “earthquake-proof” — a design later tested by 1923’s Great Kanto Earthquake, which left most of the city destroyed but the Imperial Hotel standing. By that time, the younger Wright had already acted on his inspiration to invent the similarly interlocking Lincoln Logs (see patent drawing above), which quickly proved a hit on the market. Named after the sixteenth president of the United States and the log cabin in which he’d grown up, the product tapped into American frontier nostalgia even at its debut. In the century since, Lincoln Logs have survived wartime material rationing, the rise and fall of countless toy trends, the buying and selling of parent companies, a brief and unappealing late-60s attempt to make them out of plastic, and even the Imperial Hotel itself. For “America’s national toy,” structural endurance and cultural endurance have gone together.

Related Content:

Frank Lloyd Wright Creates a List of the 10 Traits Every Aspiring Artist Needs

Frank Lloyd Wright Reflects on Creativity, Nature and Religion in Rare 1957 Audio

The Modernist Gas Stations of Frank Lloyd Wright and Mies van der Rohe

The Frank Lloyd Wright Lego Set

A is for Architecture: 1960 Documentary on Why We Build, from the Ancient Greeks to Modern Times

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

How Frank Lloyd Wright’s Son Invented Lincoln Logs, “America’s National Toy” (1916) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3eqoO0y

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment