“We will sell no wine before its time”: some Americans respond to this phrase with a chuckle of recognition, others by asking who’ll sell what wine before when. The difference must be generational, since those alive to watch television in the late 1970s and early 80s can’t have avoided hearing those words intoned on a regular basis — and in no less powerful a voice than Orson Welles’. Coming up on forty years after Citizen Kane, the former boy-wonder auteur had fallen on hard times. Struggling to complete his feature The Other Side of the Wind (little knowing that Netflix would eventually do it for him), he relied on acting work to raise professional and personal funds. He’d done it before, but now the productions offering him the most lucrative roles happened to be commercials for cheap wine.

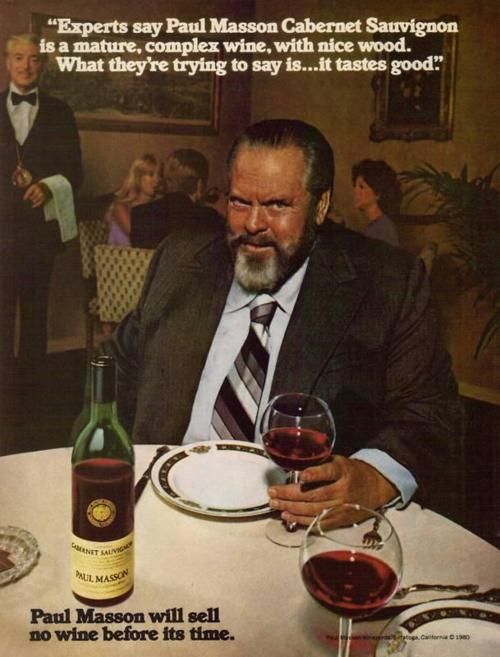

Despite having been cast into the wilderness by Hollywood, if to some degree willingly, Welles still had cultural cachet — exactly what the higher-ups at the mass-market California wine producer Paul Masson thought their brand needed. Making use of Welles’ late-period public image as a Falstaffian gourmand, Paul Masson commissioned a series of television commercials and print advertisements in which he personally endorses a range of their varietals.

In comparing Paul Masson’s “Emerald Dry” to Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony and Gone With the Wind, two works of art known for their prolonged gestation periods, Welles also implicitly acknowledged his own artistic reputation for making films of genius, if films of genius few and far between.

Though Welles balked at the effrontery of a script comparing Paul Masson wine to a Stradivarius violin, he wasn’t without genuine appreciation for the product. “Orson liked Paul Masson’s cabernet,” said John Annarino, the adman at DDB Needham who handled the Paul Masson account. “He often called the ad agency and instructed, ‘Send more red.'” He also happened to be a highly experienced booze salesman: “As early as 1945 he had done a radio spot for Cresta Blanca Wines,” writes Inside Hook’s Aaron Goldfarb. “By 1972 he was doing print work with Jim Beam bourbon. By 1975 he was hawking Carlsberg Lager. That same year, he pitched Domecq Sherry, Sandeman port (in which he portrayed their ‘Sandeman Don’ character) and Nikka Japanese Whiskey, which were a huge hit overseas.”

The campaign got Paul Masson a substantial bump in sales, but it stuck DDB Needham with a somewhat difficult star. This is evidenced not just by anecdotes from the set but surviving footage that shows Welles, far from disdainful of the wine at hand, seemingly too satisfied by it to deliver his lines properly. Much like the string of increasingly bitter complaints captured during the voiceover recording of a Findus frozen peas commercial, Welles’ seemingly drunken takes for Paul Masson — and even the finished spots — have gone viral in the internet age. Racking up millions upon millions of views on Youtube, these videos have begun to bring “We will sell no wine before its time,” a catchphrase much-referenced in the 80s, back into the zeitgeist. But then, don’t some things only improve with age?

Related Content:

An Animation of Orson Welles’ Famous Frozen Peas Rant

Orson Welles Teaches Baccarat, Craps, Blackjack, Roulette, and Keno at Caesars Palace (1978)

The Improbable Time When Orson Welles Interviewed Andy Kaufman (1982)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Watch Orson Welles’ Intoxicating Wine Commercials That Became an 80s Cultural Phenomenon is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2ZNG4pk

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment