More than 40 years after Norman Rockwell’s death, the question of whether his paintings are realistic or unrealistic remains open for debate. On one hand, critical opinion has long dismissed his Saturday Evening Post-adorning visions of American life as sheerest fantasy. “A little girl with a black eye, an elderly woman saying grace with her grandson, a boy going to war: Rockwellian scenes represent a certain sentimental America — an ideal America, or at least Rockwell’s ideal,” says a 2009 NPR story on his work.

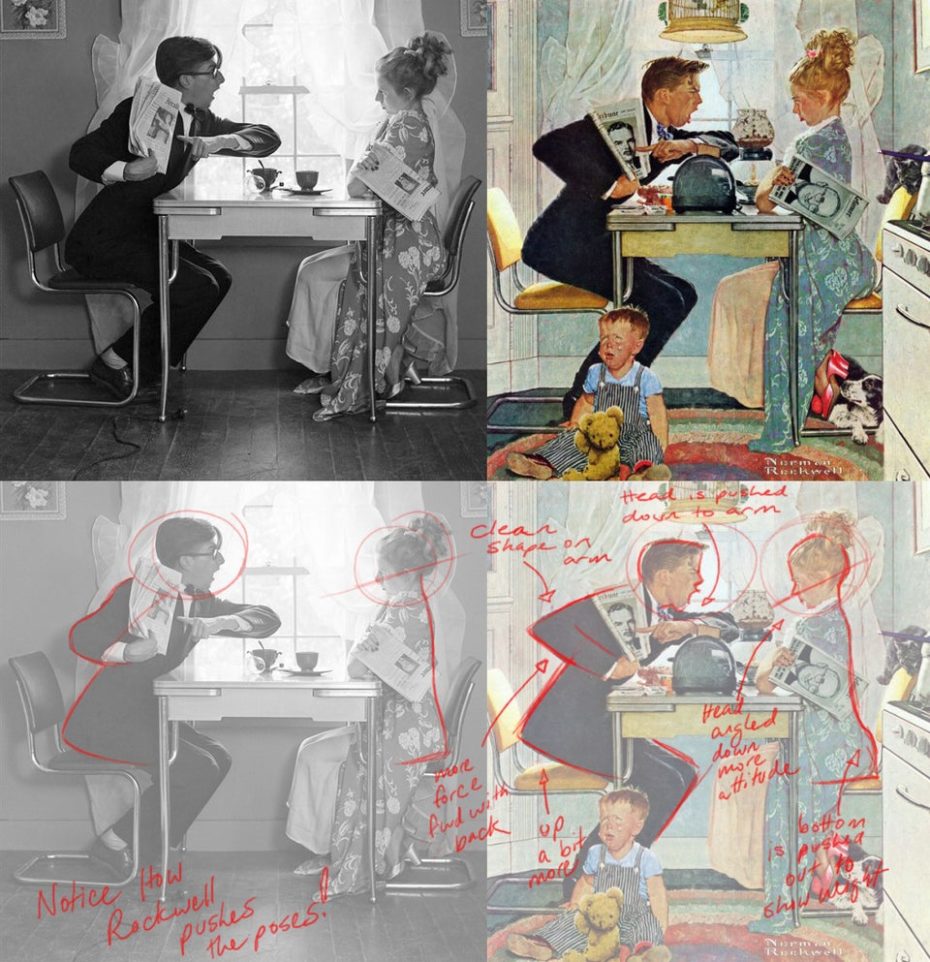

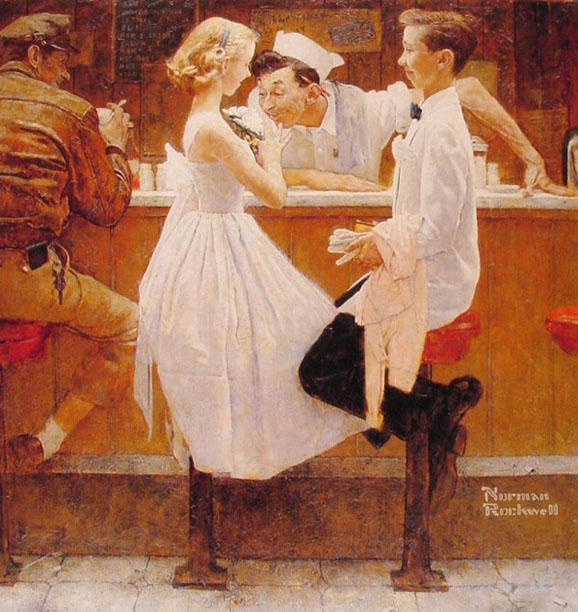

On the other hand, if Rockwell’s admirers give him a pass on this sentimentality, his detractors often turn a blind eye to his obvious technical mastery. Say what you will about his themes, the man might as well have been a camera. Indeed, his process began with an actual camera. According to that NPR piece, he “used photos, taken by a rotating cast of photographers, to make his illustrations — and all of his models were neighbors and friends,” residents of his small town of Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

The cameramen included a German immigrant named Clemens Kalischer: “An artist-photographer himself, Kalischer was at odds with the tracing techniques and saccharine subject matter in Rockwell’s work. After all, Rockwell never painted freehand, and almost all of his paintings were commissioned by magazines and advertising companies.”

But “although he may not have clicked the shutter, Rockwell directed every facet of every composition,” as you can see by examining his paintings and reference photos together, featured as they’ve been on sites like Petapixel.

At Google Arts & Culture, you can scroll through a short exhibition of Rockwell’s late work on race relations in America that reveals how he had not just one but many photographs taken as source material for each painting, which he would then combine into a single image. This quasi-cinematic “editing” process brings to mind the “storyboarding” of Edward Hopper, who stands alongside Rockwell as one of the most American painters of the 20th century.

But while Hopper gave artistic form to the country’s alienation, Rockwell — whom history hasn’t remembered as a particularly happy man — created an “American sanctuary others wished to share.” And though neither Hopper nor Rockwell’s America may ever have existed, they were crafted from the pieces of American life the artists found everywhere around them.

via Petapixel/MessyNessy

Related Content:

Norman Rockwell Illustrates Mark Twain’s Tom Sawyer & Huckleberry Finn (1936-1940)

Norman Rockwell’s Typewritten Recipe for His Favorite Oatmeal Cookies

Yale Launches an Archive of 170,000 Photographs Documenting the Great Depression

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

How Norman Rockwell Used Photographs to Create His Famous Paintings: See Side-by-Side Comparisons is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3a3ICFT

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment