The Animations That Changed Cinema: The Groundbreaking Legacies of Prince Achmed, Akira, The Iron Giant & More

Animation is childish. So believe those who never watch animated films — but also, on another, deeper level, those who hold up animated films as the most complete form of cinema. Whatever our generation, most of us alive today grew up watching cartoons meant in every sense for children, and often artistically flimsy ones at that. But even on such a low-nutrition viewing regimen, we could now and again glimpse the vast possibilities of the form. Or perhaps it was just our imagination — but then, as Stephen King once pointed out, nothing is “just” our imagination in childhood, a time when we occupy “a secret world that exists by its own rules and lives in its own culture.”

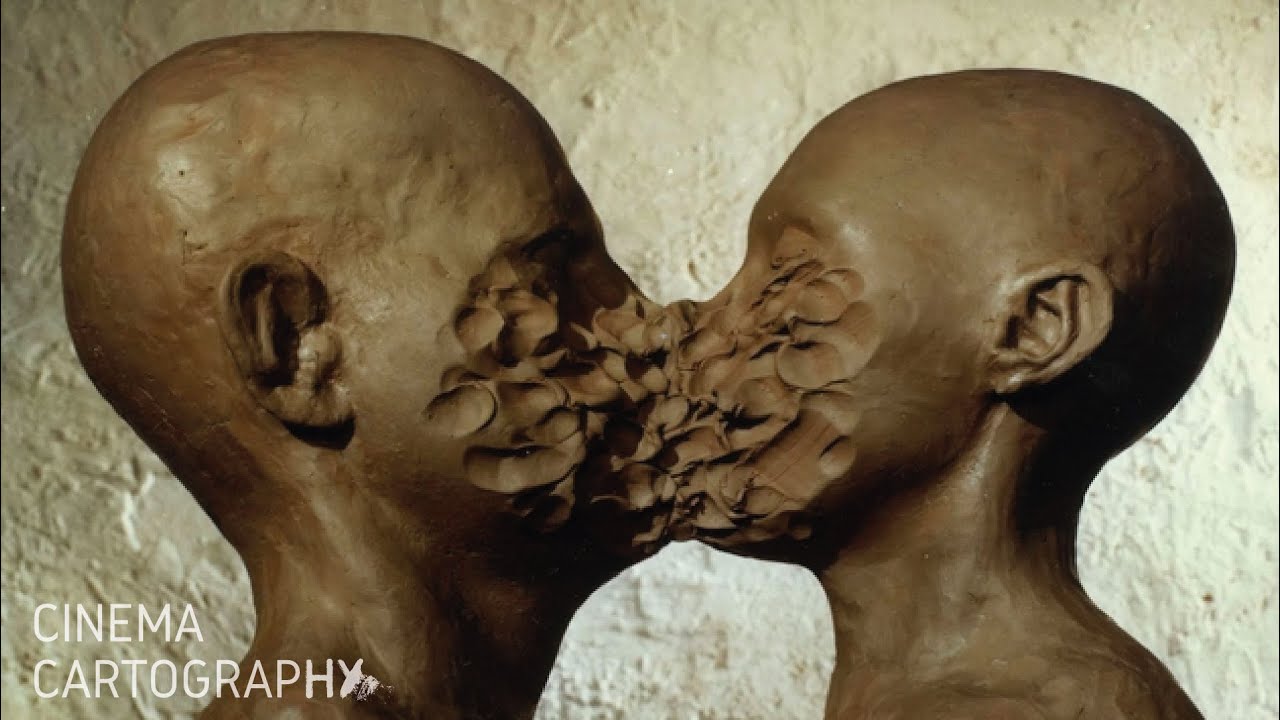

In order to navigate this reality apart, where nothing is entirely for real and nothing entirely pretend, children “think around corners instead of in straight lines.” The best animators retain this ability into adulthood, harnessing it to create a purer kind of cinema that reflects and engages the imagination in a way even the freest live-action films never can. The work of such animators constitutes the subject matter of “The Animation that Changed Cinema,” a new essay from The Cinema Cartography. In just over half an hour, the series’ creators Lewis Bond and Luiza Liz Bond explore animation produced all over the world over nearly the past century in search of the films that have widened the boundaries of the medium.

Though most video essays from The Cinema Cartography and its predecessor Channel Criswell have focused on conventional film, Bond has already demonstrated his profound understanding of animation in video essays on Studio Ghibli co-founder Hayao Miyazaki and the acclaimed cult anime series Cowboy Bebop. “The Animation that Changed Cinema” spends a great deal of time on other works from Japan, the one country that has done more than any other to elevate the animated film, including that of Miyazaki’s Ghibli partner Isao Takahata, Perfect Blue auteur Satoshi Kon, and Katsuhiro Otomo, whose Akira permanently changed much of the world’s understanding of “cartoons” as cinematic art. But as with The Cinema Cartography’s previous “The Cinematography that Changed Cinema,” the cultural-geographical mandate ranges widely.

Among these visionary animators are several previously featured here on Open Culture: the German Lotte Reiniger, creator of the all-silhouette The Adventures of Prince Achmed; Europeans from farther east (and possessed of wilder sensibilities) like Jan Švankmajer; Americans like Don Hertzfeldt, the Brothers Quay, and Wes Anderson (whose filmography includes the stop-motion The Fantastic Mr. Fox and Isle of Dogs). That last group includes even Hollywood director Brad Bird, now best known for Pixar movies like The Incredibles and Ratatouille, but here celebrated for The Iron Giant, a picture that sank upon its release, but in the two decades since has come to be appreciated as just the kind of work of art that, as Bond puts it, “makes us forget that we’re watching moving drawings” — whatever age we happen to be.

Related Content:

Free Animated Films: From Classic to Modern

How the Films of Hayao Miyazaki Work Their Animated Magic, Explained in 4 Video Essays

What Made Studio Ghibli Animator Isao Takahata (RIP) a Master: Two Video Essays

How Master Japanese Animator Satoshi Kon Pushed the Boundaries of Making Anime: A Video Essay

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

The Animations That Changed Cinema: The Groundbreaking Legacies of Prince Achmed, Akira, The Iron Giant & More is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2Og3H7u

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment