Learning to play chess first necessitates learning how each piece moves. This is hardly the labor of Hercules, to be sure, though it does come down to pure memorization, unaided by any verbal or visual cues. Does the name “pawn,” after all, sound particularly like something that can only step forward? And what about the shape of the knight suggests the shape of the knight’s move? The form of a chess piece, in other words, doesn’t follow its function — and under certain sets of aesthetic principles, there could be few greater crimes. Leave it to a member of the Bauhaus, the art school and movement that aimed to unify not just form and function but art, craft, and design — to bring them all into line.

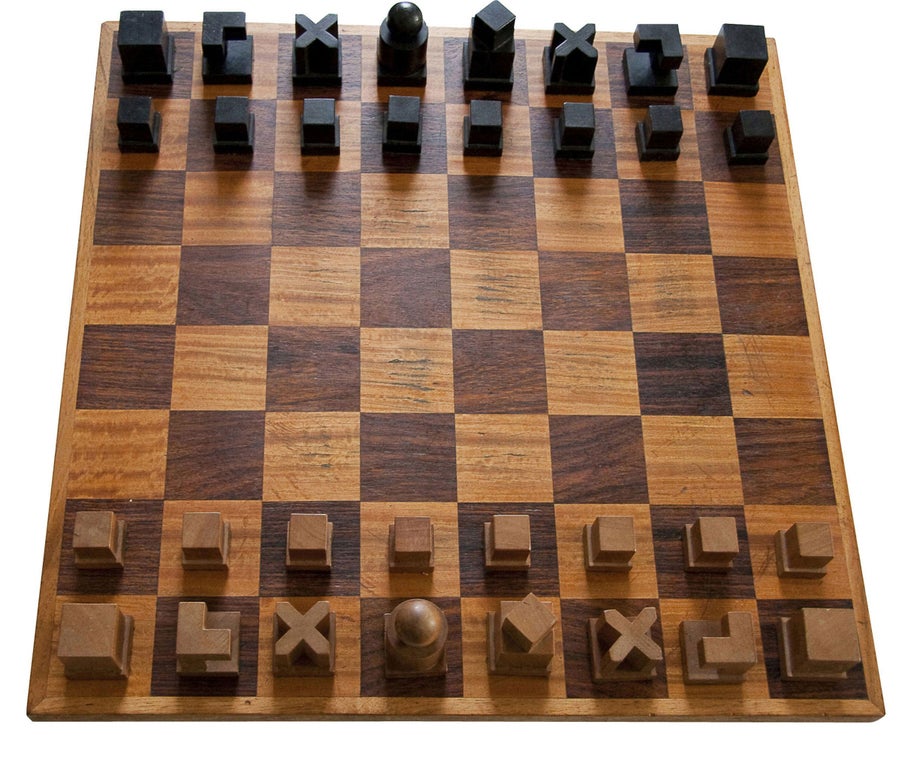

Brought into the Bauhaus in 1921 by its founder Walter Gropius, the sculptor Josef Hartwig began work on his redesigned chess set the following year. In all its iterations, the pieces takes on forms made of simple shapes: “The sphere, double cube, and three sizes of block, singly or combined, yield pieces that, despite their highly geometric stylization, are strongly suggestive of their rank or power,” says the Metropolitan Museum of Art, owner of one of one of Hartwig’s original sets.

“The bishops are clearly implied by the cross outline, and the rooks by the simple stability of a cube. Most ingenious of all are the knights, formed of three double cubes joined in such a fashion that each face of the resulting form shows two cubes one above the other and a third on the side, an embodiment of the knight’s move.”

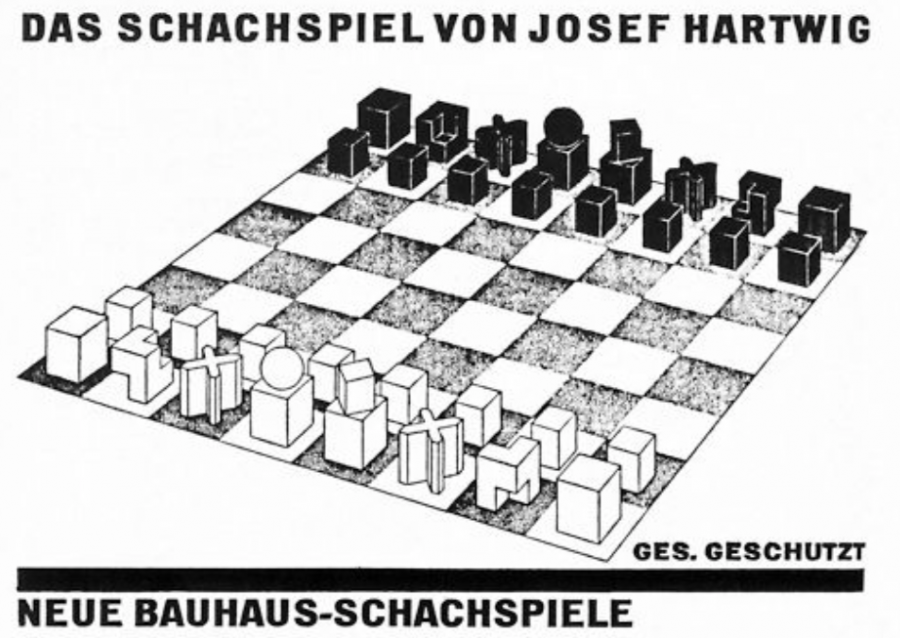

Like many Bauhaus works, Hartwig’s chess set found a dual existence as both a piece of art and a consumer good. The artist himself also “made a poster to talk about his product” and “a box to package it,” says cuator Anne Monier in the video above, “so we really are in a total creation around a game of chess.” In addition to making the game’s movements easier to learn, it also constitutes a visual demonstration of what it means for form to follow function. The idea, says Monier, is “to spread the ideas of the Bauhaus in people’s everyday life, to be able in fact to change the living environment, to take part in creating a new society.” The video comes from Bauhaus Movement, an online shop where you can invite the spread into your home by ordering a replica Hartwig chess set. It’ll set you back €495, but ideals, now as in the heyday of the Bauhaus, don’t come cheap.

Related Content:

Harvard Puts Online a Huge Collection of Bauhaus Art Objects

The Politics & Philosophy of the Bauhaus Design Movement: A Short Introduction

Marcel Duchamp, Chess Enthusiast, Created an Art Deco Chess Set That’s Now Available via 3D Printer

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

The Bauhaus Chess Set Where the Form of the Pieces Artfully Show Their Function (1922) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2YBXIfk

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment