Behold All 42 Maps from Jules Verne’s Extraordinary Voyages, the Author’s 54-Volume Collection of “Geographical Fictions”

Jules Verne’s tales of adventure take his characters around the world, through the deepest seas, even into the center of the Earth—on journeys, that is, difficult or impossible in the 19th century. Verne himself, however, spent most his life in France, writing of places he had not seen. In one apocryphal story, the young Jules Verne is caught trying to sneak aboard a ship bound for the Indies and promises his father he will henceforth travel “only in his imagination.” Whether or not he made such a vow, he seemed to keep it, though the idea that he never traveled at all is a “tiresome canard,” writes Terry Harpold in an essay titled “Verne’s Cartographies.”

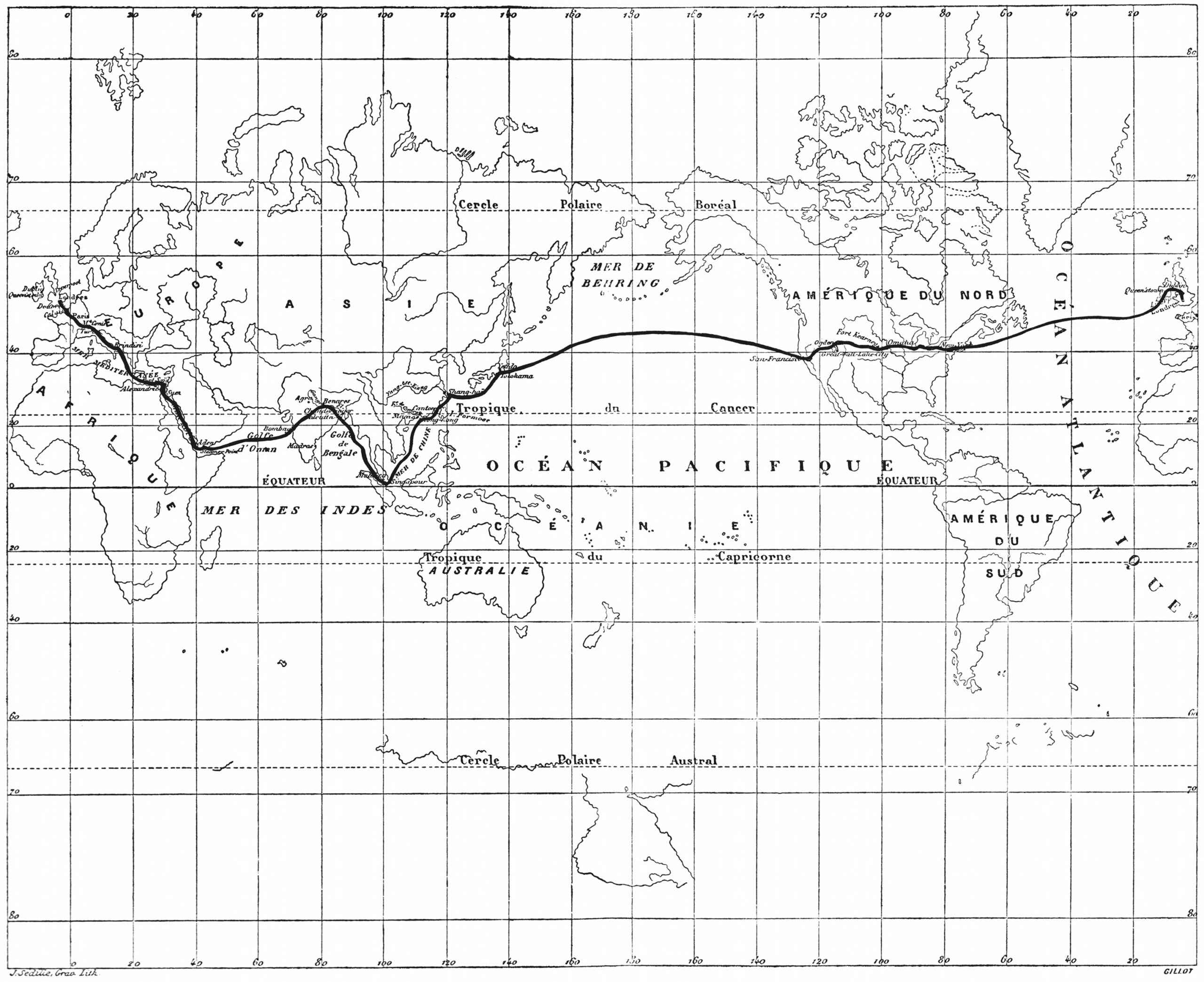

Verne’s famed novels Twenty Leagues Under the Sea, Journey to the Center of the Earth, and Around the World in Eighty Days constitute only a fraction of the 54-volume Voyages Extraordinaires, a collection of fiction conceived on the basis of a science we might not think of as a rich field for material.

“Of the 80 novels and other short stories he published,” geographer Lionel Dupuy writes, “62 make up the corpus of Extraordinary Voyages (Voyages Extraordinaires). These books, in which imagination played a vital role, were termed ‘geographical novels,’ a category the author himself used for them.”

Verne would also use the term “scientific novel,” but he made it clear which science he meant:

I always had a passion for studying geography, as others did for history or historical research. I really believe that it is my passion for maps and great explorers around the world that led me to write the first of my long series of geographical novels.

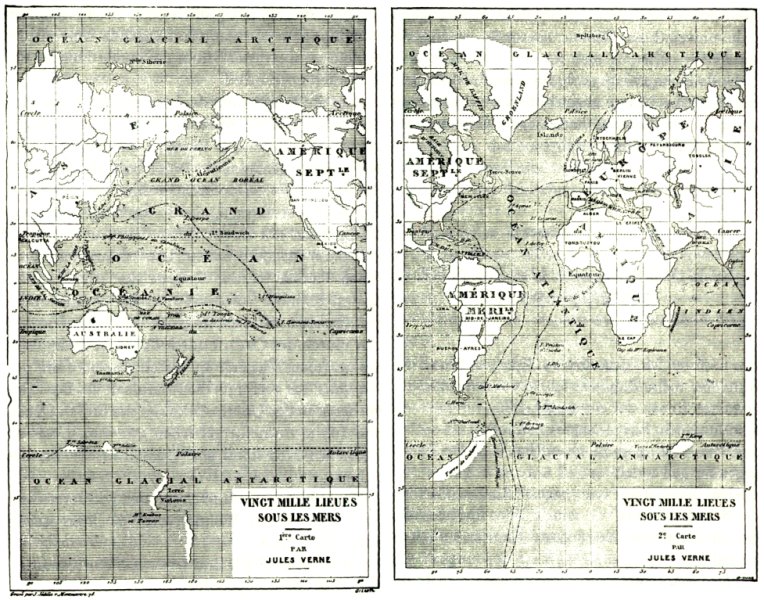

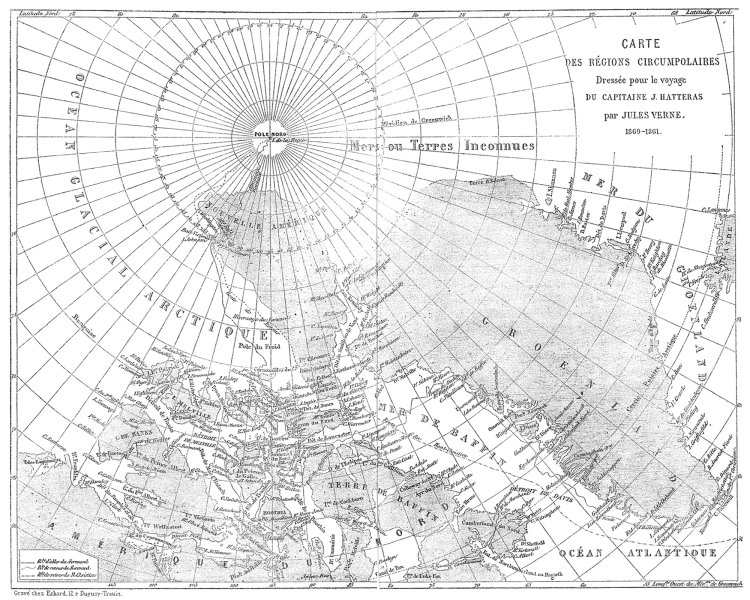

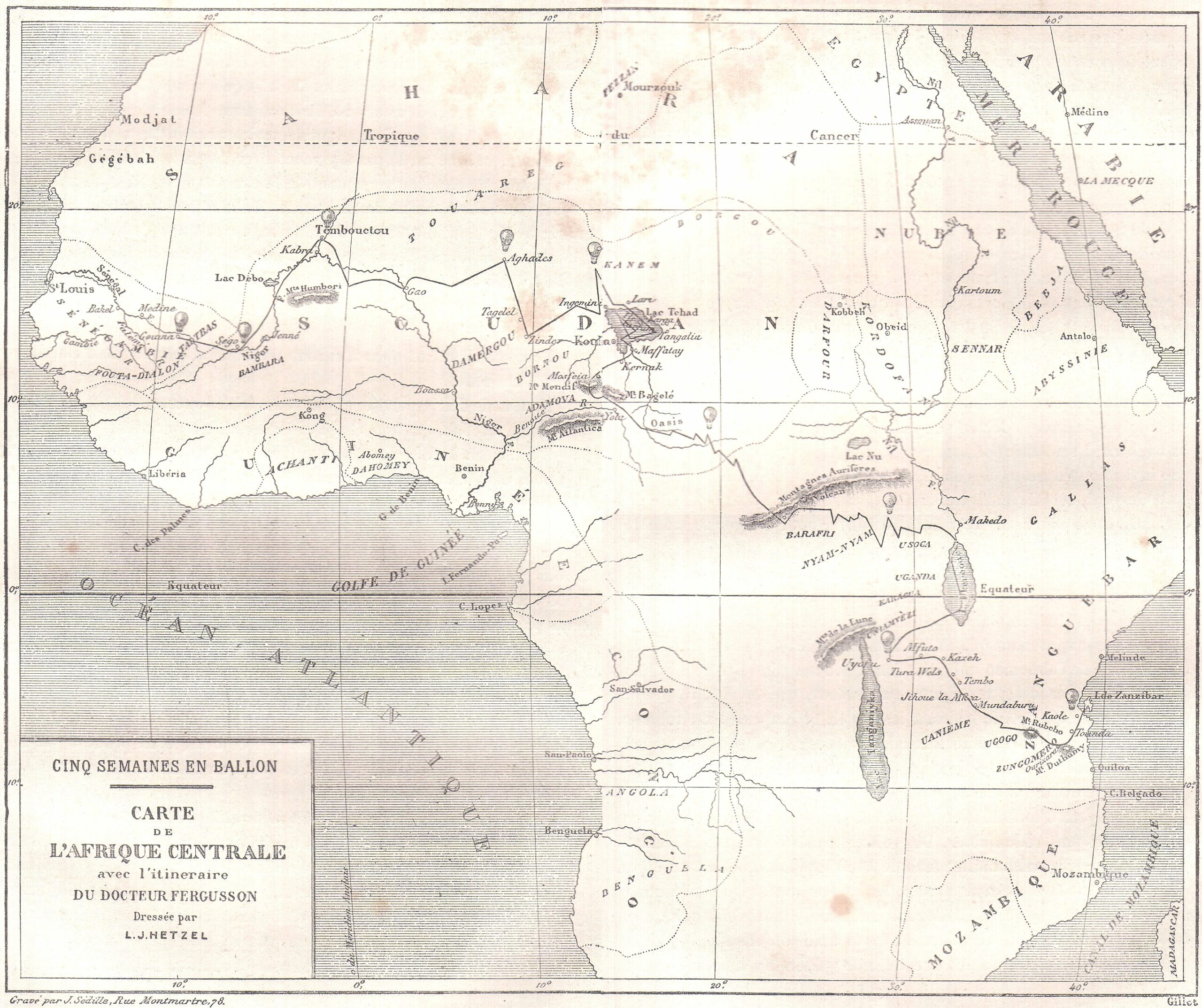

As a geographical novelist, and member of the Geographical Society from 1865 to 1898, it was only fitting that Verne include as many maps as he could in his quest, as he put it, “to depict the Earth, and not just the Earth, but the universe, for I have sometimes carried my readers far away from the Earth in my novels.” To that end, “thirty of the novels” in the first edition of Voyages Extraordinaires” published by Pierre-Jules Hetzel, “include one or more engraved maps,” Harpold points out. “There are forty-two such engravings in all.” View them here.

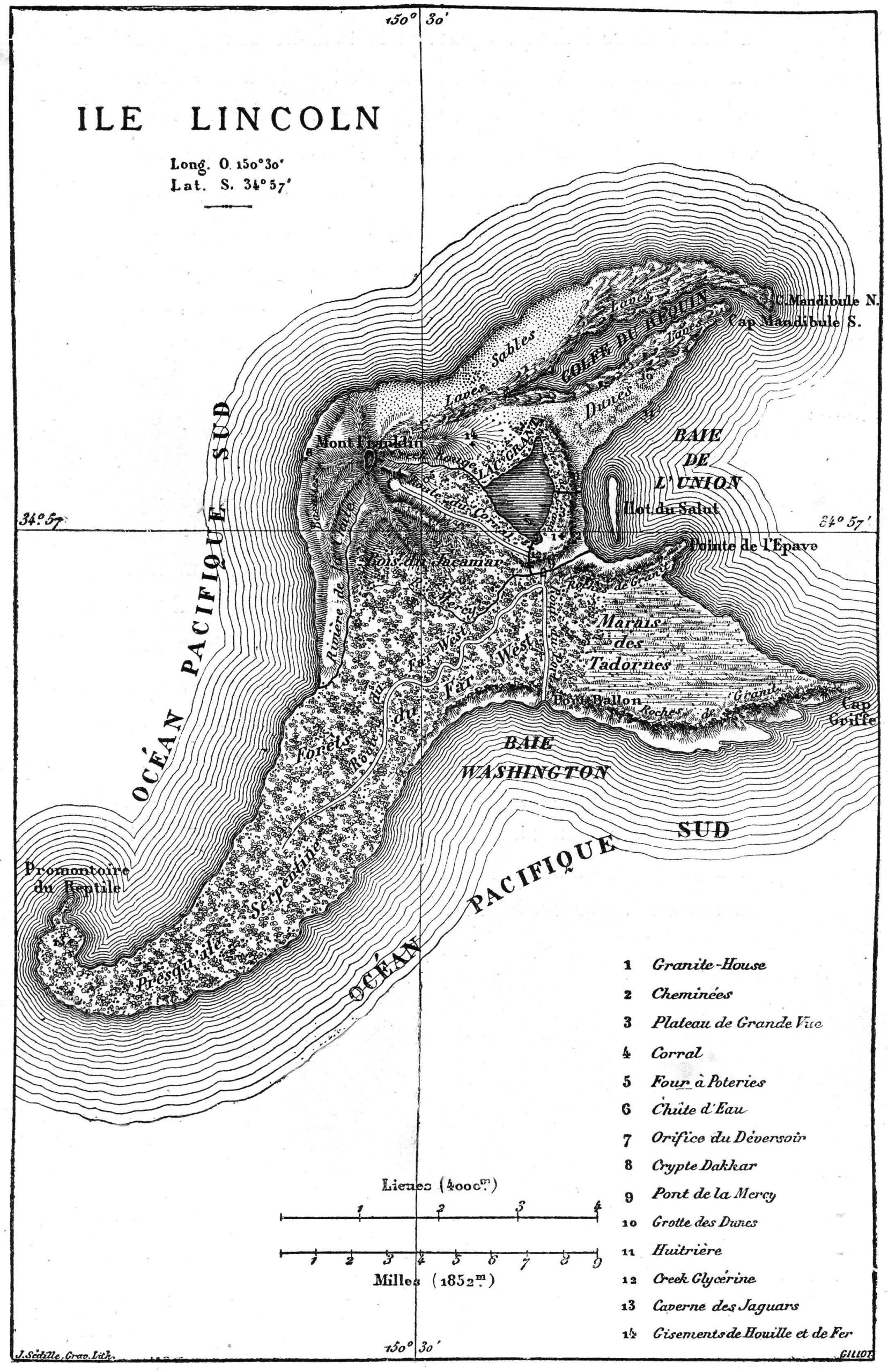

“These images and design elements are nuanced, graceful, and evocative; drafted and engraved by some of the finest artists of the time,” Harpold writes. “They represent the pinnacle of late nineteenth-century popular-scientific cartography.” They also represent the author of geographical fictions who, as both a scientist and artist, refused to let either form of thinking take over the text, combining myth and poetry with observation and measurement. As Dupuy puts it, “in Extraordinary Voyages, the passage from reality to imagination and back is encouraged by the emergence of a ‘marvelous’ that we can call ‘geographical.’”

In one sense, we might think of most kinds of fiction as geographical, in that they describe places we have never seen. This is particularly so in fictions that include maps of their imagined territories, such as those of William Faulkner, J.R.R. Tolkien, Robert Louis Stevenson, and so on. We might look to Jules Verne as their towering forbear. “Several of the maps appearing in the Hetzel Voyages were drafted under Verne’s close supervision or were based on his sketches or designs. Maps in three of the novels (20,000 Leagues [top], Hatteras [further up], Three Russians) were drafted by Verne himself, whose talents in this regard were appreciable,” writes Harpold.

Verne’s maps mix real and fictional place names and are “always ambiguous and semiotically unstable objects.” They appear almost as admissions of the mythmaking that goes into the science of geography and the act of exploration. Near the end of his life, maps became more real to Verne than the world outside. As he grew too weary even to leave the neighborhood, he wrote to Alexandre Dumas fils, “If I have maintained a taste for work… , nothing remains of my youth. I live in the heart of my province and never budge from it, even to go to Paris. I travel only by maps.” See all of Verne’s maps from the Hetzel edition of Extraordinary Voyages, such as those for Around the World in Eighty Days (above) and Five Weeks in a Balloon (below), here.

Related Content:

William Faulkner Draws Maps of Yoknapatawpha County, the Fictional Home of His Great Novels

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Behold All 42 Maps from Jules Verne’s Extraordinary Voyages, the Author’s 54-Volume Collection of “Geographical Fictions” is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3tMSn37

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment