Nina Simone’s creative and political community meant everything to her, and the many losses she suffered in the 60s sent her deeper into the depression of the last decades of her life. “Langston Hughes, James Baldwin, and Lorraine Hansberry [were] prominent,” writes Malik Gaines at LitHub, “among… socially engaged writers and dramatists” whom she considered not only her “political tutors” but also her heroes and closest friends. She never stopped grieving the loss of Hansberry and Hughes and frequently memorialized them in tributes like “Backlash Blues."

Written by Hughes, and one of Simone's fiercest and most timely civil rights songs, “Backlash Blues” represents the significant influence the poet had on her and her art. In a live 1967 recording, she sings, “When Langston Hughes died—He told me many months before—Nina keep working until they open up that door.” The two first met when Simone was still Eunice Waymon from Tryon, North Carolina: an aspiring classical pianist, “president of the 11th-grade class and an officer with the school’s NAACP chapter,” explains Andrew J. Fletcher, a board member of the Nina Simone Project in Asheville.

This was 1949, and Hughes had come to Asheville to address Allen High School, the private school for African American girls Simone attended through a scholarship that her music teacher and early champion collected from her hometown. The poet “could not have known,” Maria Popova writes at Brain Pickings, “that [Simone] would soon revolutionize the music canon under her stage name." But nearly ten years later, he recognized her talent immediately.

On the release of Simone's first album, Little Girl Blue, Hughes was “so stunned that he lauded it with lyrical ardor” in his column for the Chicago Defender.

She is different. So was Billie Holiday, St. Francis, and John Donne. So in Mort Sahl. She is a club member, a coloured girl, an Afro-American, a homey from Down Home. She has hit the Big Town, the big towns, the LP discs and the TV shows — and she is still from down home. She did it mostly all by herself. Her name is Nina Simone.

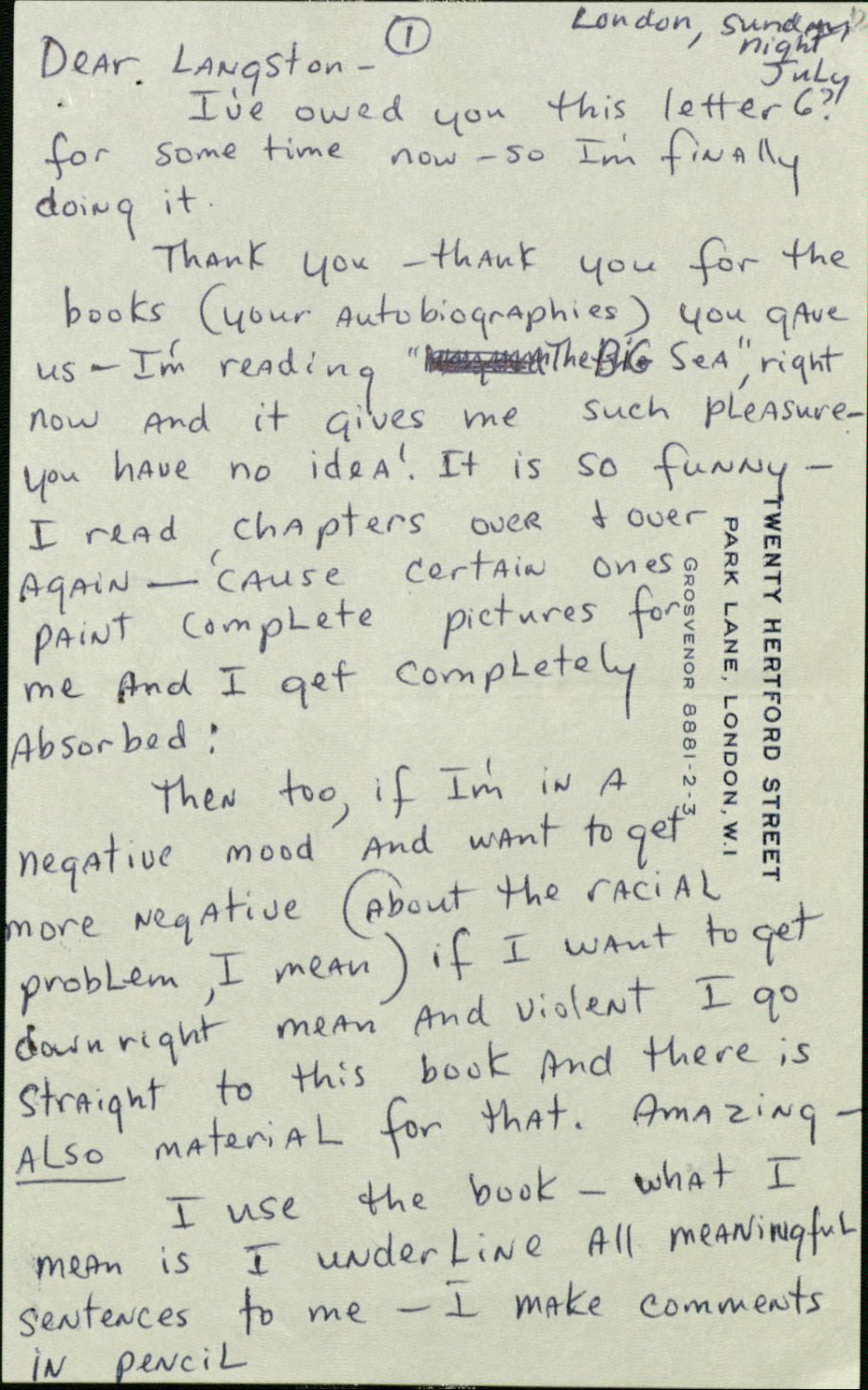

They would become close friends and mutual admirers. Hughes sent her “books he thought would inspire her,” including several of his own, and wrote "words for her to set to song.” She wrote to him with earnest expressions of appreciation, especially in the letter here, penned in 1966 just before Hughes' death.

Simone had just read Hughes' autobiography The Big Sea. The book, she says, “gives me such pleasure—you have no idea! It is so funny.” She also writes, with candor:

Then too, if I’m in a negative mood and want to get more negative (about the racial problem, I mean) if I want to get downright mean and violent I go straight to this book and there is also material for that. Amazing—

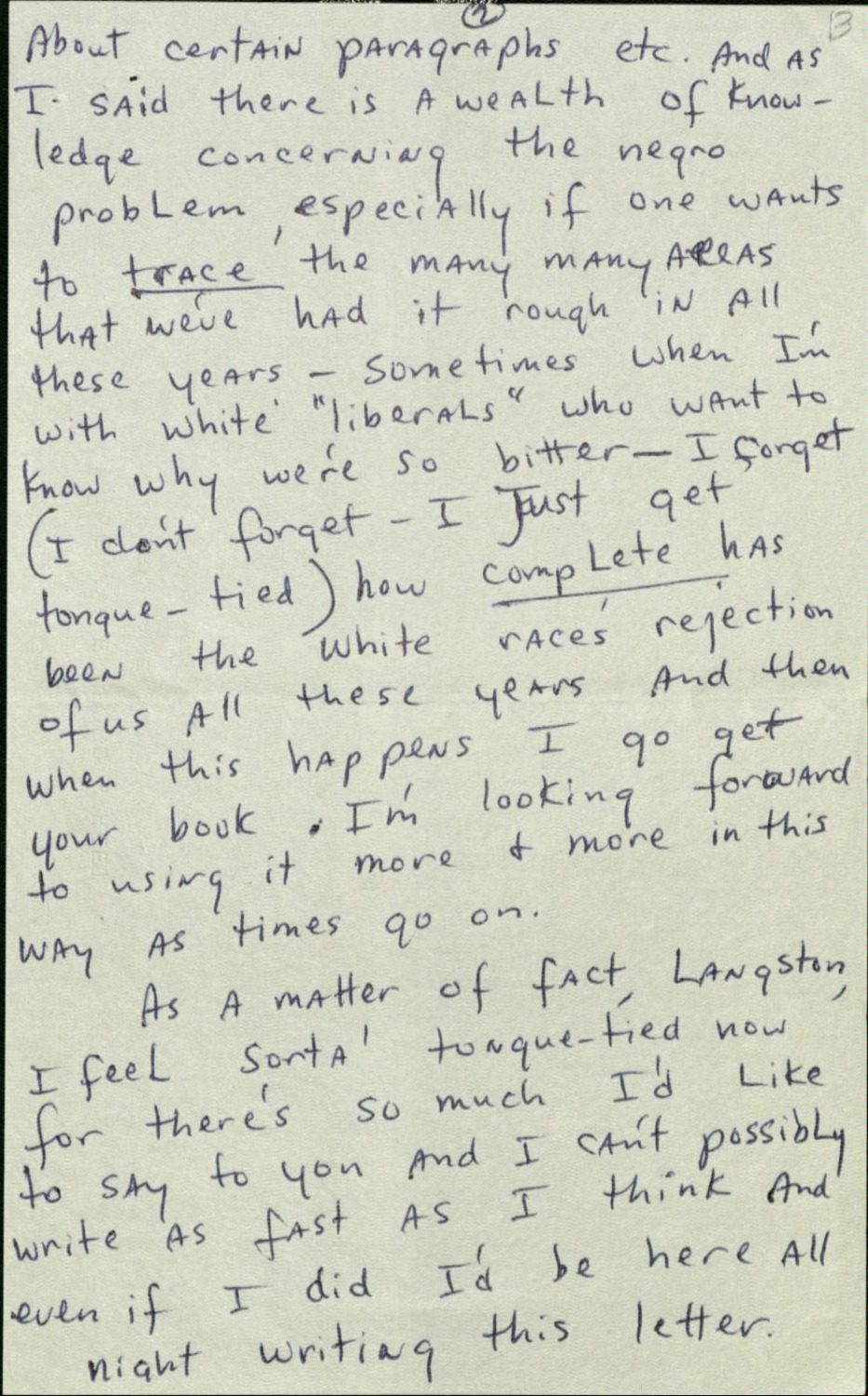

I use the book—what I mean is I underline all meaningful sentences to me…. And as I said there is a wealth of knowledge concerning the negro problem, especially if one wants to trace the many many areas that we’ve had it rough in all these years—sometimes when I’m with white “liberals” who want to know why we’re so bitter—I forget (I don’t forget—I just get tongue-tied) how complete has been the white races’ rejection of us all these years and then when this happens I go get your book.

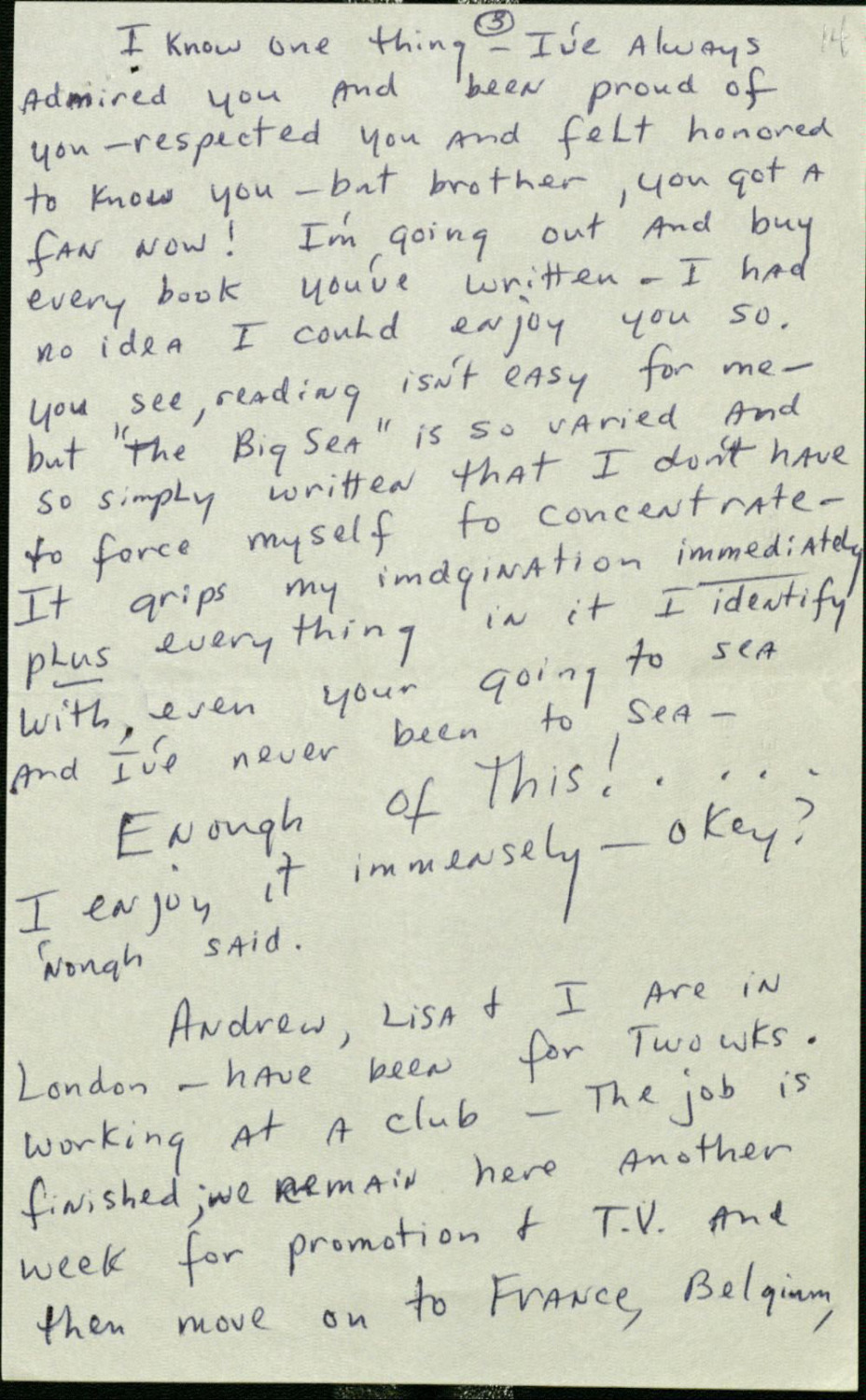

Hughes’ is rarely “mean and violent,” but Simone brought to her reading her own despair and rage and raw sense of rejection, emotions she was never afraid to explore in her work or talk about with humor and fierce ire in her life. “Brother, you’ve got a fan,” she gushes. The Big Sea “grips my imagination immediately plus everything in it I identify with, even your going to sea and I’ve never been to sea.” She had not been to sea, but she had been adrift, “depressed, alienated and low,” as she sang at Morehouse College in 1969 in a performance of her civil rights anthem and tribute to Lorraine Hansberry, “To Be Young, Gifted and Black.”

The adlib framed Simone’s feelings with the same "emotional and political dimensions,” writes Gaines, she found in Hughes’ work. Though she does not mention it in her letter, her annotated copy of The Big Sea surely marks up the passage below, in which Hughes’ describes his early unhappiness and his transformative encounter with art:

When I was in the second grade, my grandmother took me to Lawrence to raise me. And I was unhappy for a long time, and very lonesome, living with my grandmother. Then it was that books began to happen to me, and I began to believe in nothing but books and the wonderful world in books--where if people suffered, they suffered in beautiful language, not in monosyllables, as we did in Kansas.

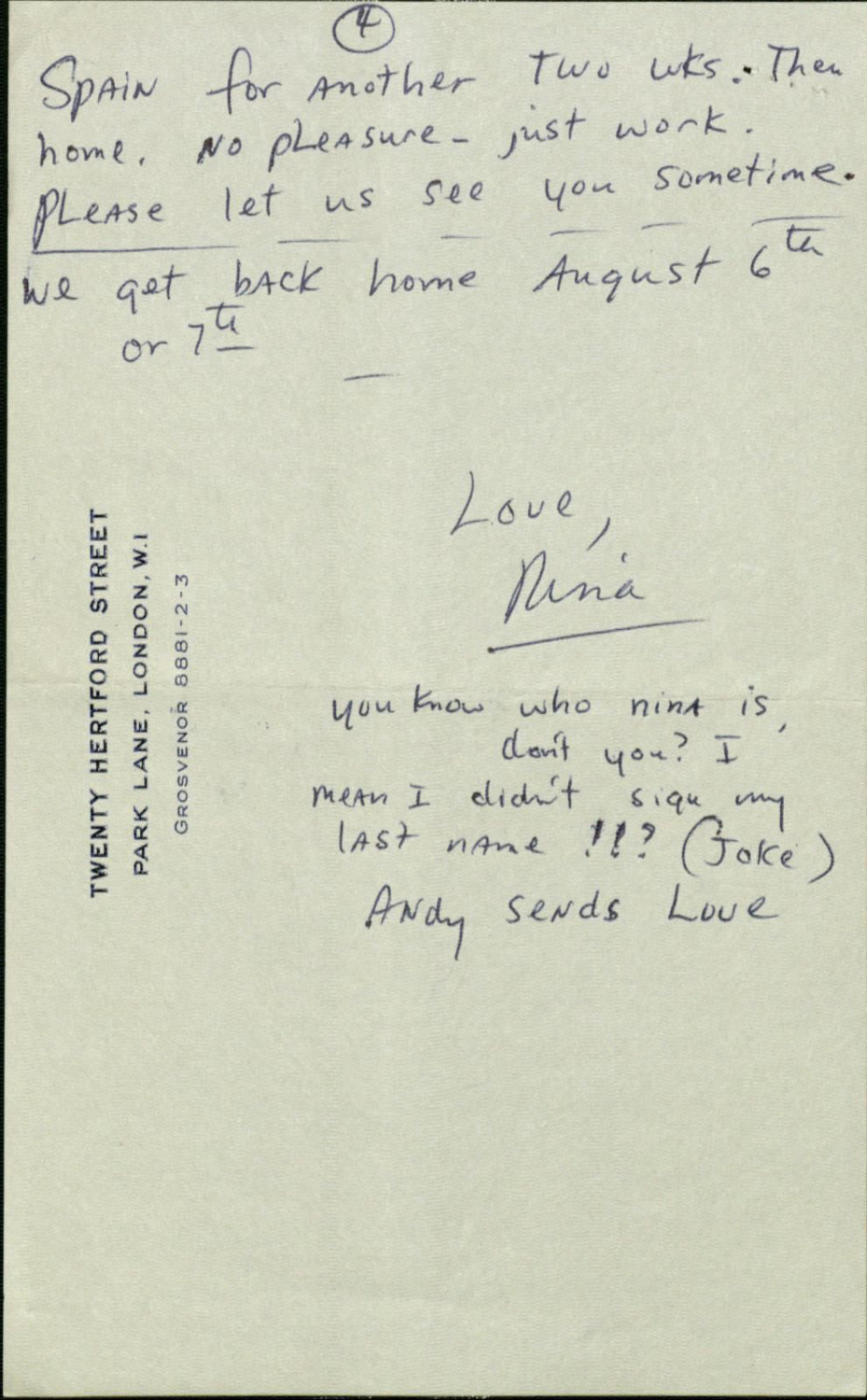

For Simone, music gave her suffering purpose, but not the music she played for audiences and on record. One of the saddest ironies of her career is that the woman dubbed “The High Priestess of Soul” had little interest in playing soul. She embarked on her popular music career to fund her classical education. However, the opportunities to play the way she wanted to did not arise. “Nina closed her letter on a strangely down note,” writes Nadine Cohodas in Princess Noire: The Tumultuous Reign of Nina Simone. “Her melancholy overwhelmed any excitement about playing for the first time in France and Belgium. ‘No pleasure,’ she told Langston, ‘just work.’”

So much of Simone’s frustration and burnout in the music industry came out of a deep sense of alienation from her work. The shy Eunice Waymon had never craved the spotlight, something Hughes must have come to know about her in the years of their acquaintance. In his first note of praise, however, he gets one thing wrong. As she was always the first to point out, Simone did not do it “mostly all by herself.”

The support of her mother, her teacher, and her small "down home" community took her as far as it could. Her relationships with Hansberry, Hughes, and other artists/activists carried her the rest of the way. Until they were gone. But when Hughes died, Popova writes, “a devastated Simone turned her coveted set at the Newport Jazz Festival into a tribute and closed it with an exhortation to the audience: ‘Keep him with you always. He was a beautiful, a beautiful man, and he’s still with us, of course.'” See much more of their correspondence at the Beinecke.

via the Beinecke

Related Content:

Nina Simone’s Live Performances of Her Poignant Civil Rights Protest Songs

Nina Simone Song “Color Is a Beautiful Thing” Animated in a Gorgeous Video

Langston Hughes Reads Langston Hughes

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Nina Simone Writes an Admiring Letter to Langston Hughes: “Brother, You’ve Got a Fan Now!” (1966) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/32fdyhg

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment