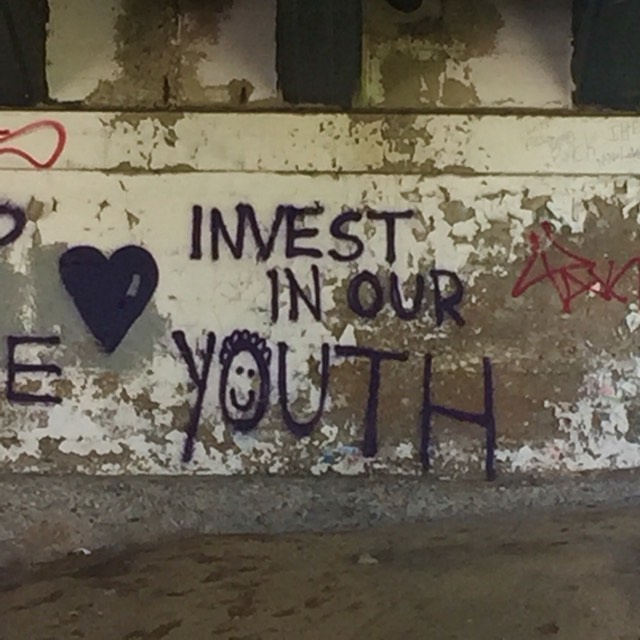

What happens when anti-racist protesters gather in the streets and are not met with tear gas, rubber bullets, and batons? For one thing, they make art and graffiti. Lots of it, on walls, streets, sidewalks, courthouse doors, the plywood of boarded-up windows, wherever. Public activist art serves not only as a memorial for victims of state oppression, but as a way to imagine what the future needs and visually occupy the space to make it happen. In the intertwining “mutual relations of the political and the aesthetic,” symbols can begin to call real conditions into existence.

The streets of cities around the country have become temporary galleries of artworks that remember victims of systemically racist police violence and call for justice, even as they imagine what a more just world might look like: one where people are not trapped in cycles of poverty by austerity and state violence.

Such displays have proliferated especially in Minneapolis, where George Floyd was killed. There, the “memorial… is constantly changing. In the days following Floyd’s murder by the police, street art, flowers, handwritten notes, and more” appeared.

Now the site “has become a living space,” Todd Lawrence, a professor at the University of St. Thomas, tells Leah Feiger at Hyperallergic. “The state of flux characterizes much of Minneapolis’s street art scene in the wake of recent protests,” Feiger writes. “The ownership of the physical art is contentious,” and temporary installations become sites of long-term debate. The University of St. Thomas has decided to preserve these ephemeral statements in a database called Urban Art Mapping: George Floyd & Anti-Racist Street Art. The project began with a focus on Minneapolis and has “steadily expanded with every new submission.”

The project includes in its wider scope a database of COVID-19 street art, with many an acknowledgement of how government failures in response to the pandemic connect to the willful disregard for human life the Black Lives Matter movement calls out. “Artists and writers producing work in the streets—including tags, graffiti, murals, stickers, and other installations on walls, pavement, and signs—are in a unique position to respond quickly and effectively in a moment of crisis,” notes the COVID-19 Street Art site. As we limit our movement through public space, that space itself transforms, responding in direct ways to a multitude of intersecting crises none of us can afford to ignore.

Make submissions to the COVID-19 Street Art archive here and to the George Floyd & Anti-Racist Street Art archive here.

Related Content:

Public Enemy Releases a Fiery Anti-Trump Protest Song (NSFW)

How Jazz Helped Fuel the 1960s Civil Rights Movement

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

A New Digital Archive Preserves Black Lives Matter & COVID-19 Street Art is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/34wkvNy

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment