When People Gave Anti-Valentine’s Day Cards: Revisit the “Vinegar Valentines” That Spread Ridicule and Contempt

Krampus—the Christmas “half goat, half demon” of Germanic folklore—has become a figure of some fascination in popular culture recently. We might call the appetite for this “anti-St. Nicholas… who literally beats people into being nice and not naughty,” National Geographic writes, a testament to a widespread sentiment: Hang the forced cheer, Christmas can be dreadful.

How much more so can Valentine’s Day feel like a big con, cooked up by marketers and chocolatiers? Though established 200 years after the saint’s 3rd century A.D. martyrdom, and linked with romantic love by Geoffrey Chaucer in the 14th century, its status as a day to overspend has more modern origins. Even some of us who dutifully buy jewelry, flowers, and cards each year may wish for a Valentine’s Day Krampus.

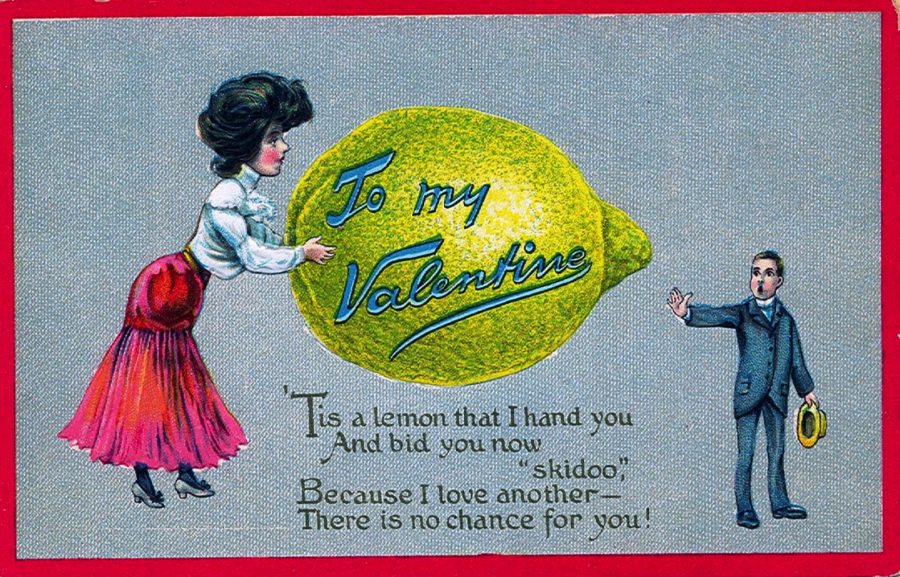

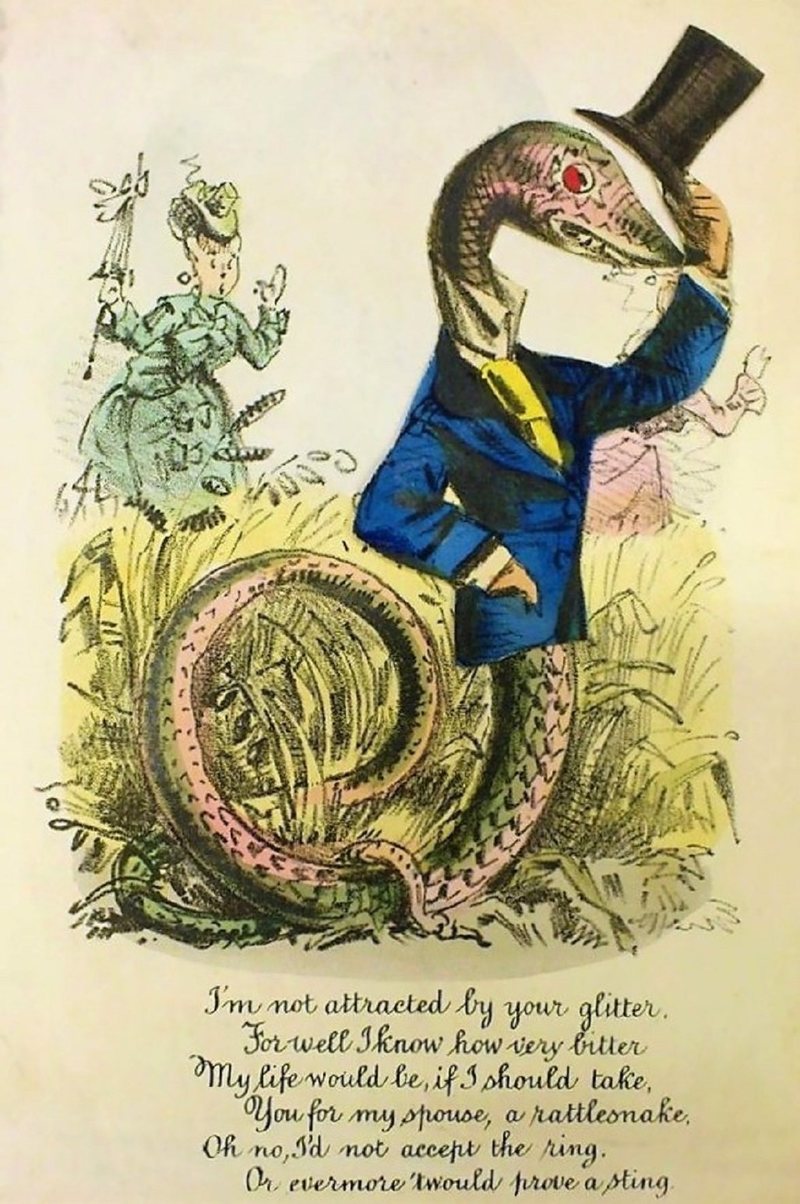

If you count yourself among those humbugs, you’ll be happy to learn about a once-rich anti-Valentine’s Day tradition “during the Victorian era and the early 20th century,” as Becky Little writes at Smithsonian, “February 14 was also a day in which unlucky victims could receive ‘vinegar valentines’ from their secret haters.” Like the choices of Santa or Krampus, tricks or treats, one could make the holiday about love or hate.

One scholar, Annebella Pollen, who has written on the subject “says that people often ask her whether these cards were an early form of ‘trolling.’” Perhaps that’s not an entirely accurate comparison. Trolls like hoaxes, and mostly like to witness the reactions to their provocations. But Valentines cynics proceeded with the same cruel glee. As Atlas Obscura notes, anti-Valentines were meant to wound and shame, Krampus-like. Their appeal proved profitable:

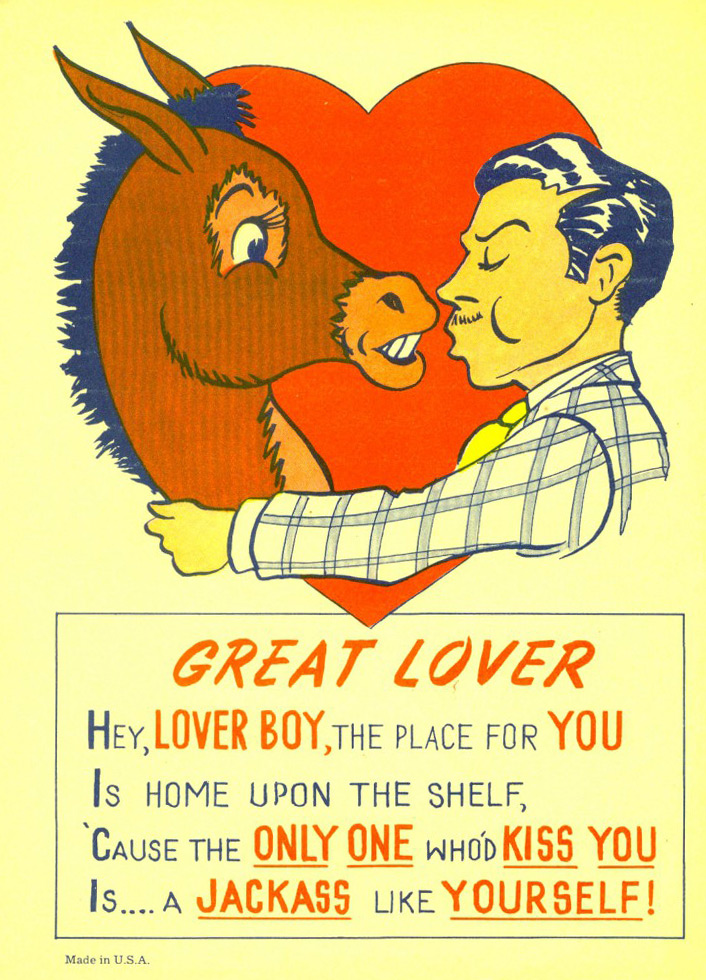

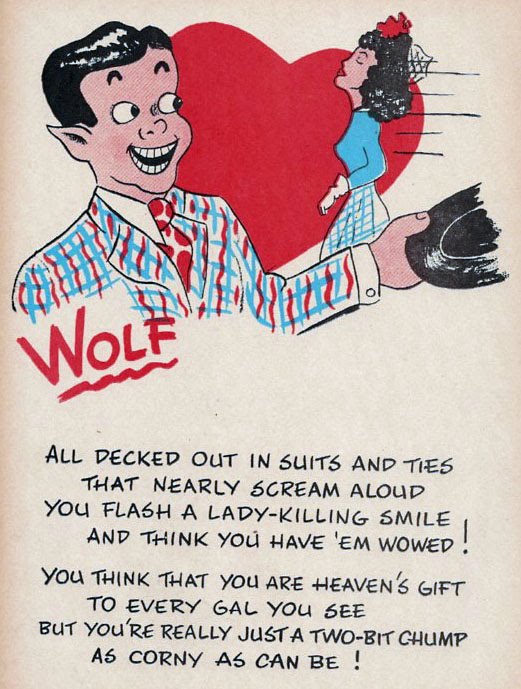

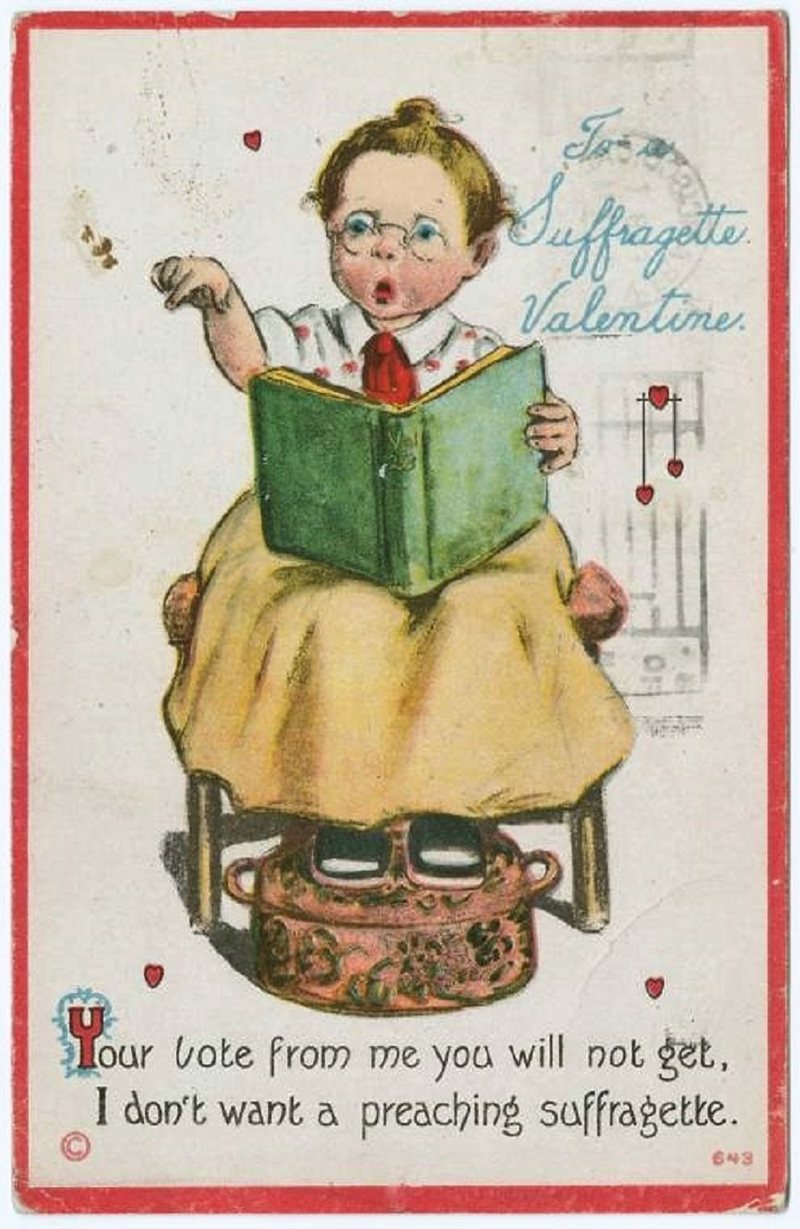

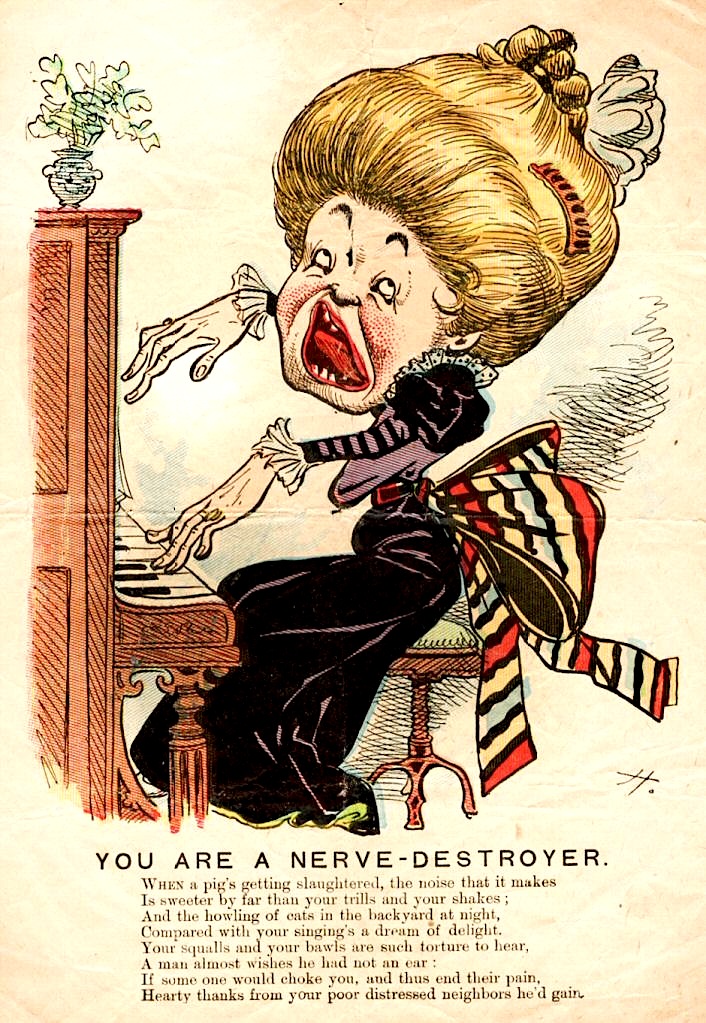

Vinegar valentines were commercially bought postcards that were less beautiful than their love-filled counterparts, and contained an insulting poem and illustration. They were sent anonymously, so the receiver had to guess who hated him or her; as if this weren’t bruising enough, the recipient paid the postage on delivery. In Civil War Humor, Cameron C. Nickels wrote that vinegar valentines were “tasteless, even vulgar,” and were sent to “drunks, shrews, bachelors, old maids, dandies, flirts, and penny pinchers, and the like.” He added that in 1847, sales between love-minded valentines and these sour notes were split at a major New York valentine publisher.

Some vinegar valentines publishers had another thing in common with modern-day trolls: they capitalized on a hatred of feminism. “The women’s suffrage movement of the late 19th and early 20th century brought another class of vinegar valentines, targeting women who fought for the right to vote.” These portrayed suffragists as ugly, abusive, and undesirable, a stereotype found in the world of sincere valentines as well. One such card “depicted a pretty woman surrounded by hearts, with a plain appeal: 'In these wild days of suffragette drays, I’m sure you’d ne’er overlook a girl who can’t be militant, but simply loves to cook.'”

Vinegar valentines (a later name—they were called “comic valentines” at the time) prompted all the sorts of concerns we’re used to seeing. Teachers worried about the effect of such commercialized emotional cruelty on their students. One magazine enjoined teachers to make Valentine’s Day “a day for kind remembrance than a day for wrecking revenge.” But where’s the fun in that? Vinegar valentines, says Pollen, “were designed to expand this holiday into something that could include a whole range of different people and a whole range of different emotions,” including some very un-Valentine's Day-like contempt.

Find a big collection of Vinegar Valentines at Collector's Weekly.

via 41 Strange

Related Content:

Celebrate Valentine’s Day with a Charming Stop Motion Animation of an E.E. Cummings’ Love Poem

Tom Waits Shows Us How Not to Get a Date on Valentine’s Day

Franz Kafka’s Kafkaesque Love Letters

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

When People Gave Anti-Valentine’s Day Cards: Revisit the “Vinegar Valentines” That Spread Ridicule and Contempt is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2u3bkUU

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment