A Map of the Disney Entertainment Empire Reveals the Deep Connections Between Its Movies, Its Merchandise, Disneyland & More (1967)

We all remember the first Disney movie we ever saw. In most of our childhoods, one Disney movie led to another, which stoked in us the desire for Disney toys, Disney games, Disney comics, Disney music, and so on. If we were lucky, we might also take a trip to Disneyland or one of its descendants elsewhere in the world. Many of us spent the bulk of our youngest years as happy residents of the Disney entertainment empire; some of us, into adulthood or even old age, remain there still.

Die-hard Disney fans appreciate that the world of Disney — comprising not just films and theme parks but television shows, printed matter, attractions on the internet, and merchandise of nearly every kind — is too vast ever to comprehend, let alone fully explore.

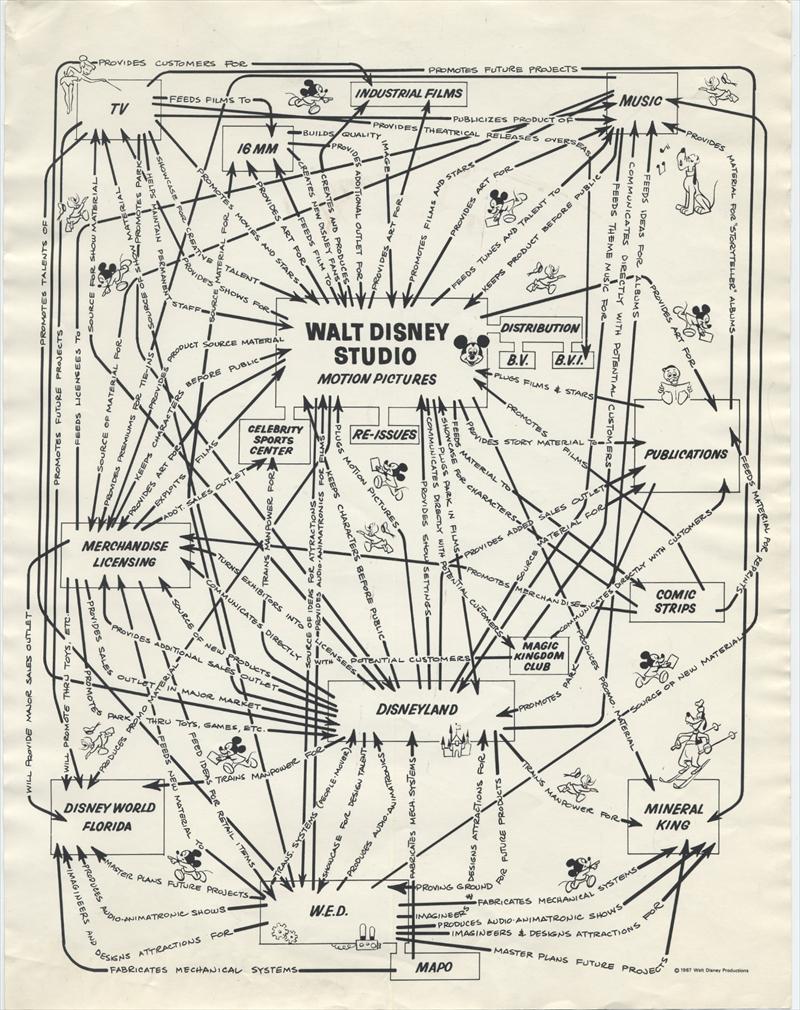

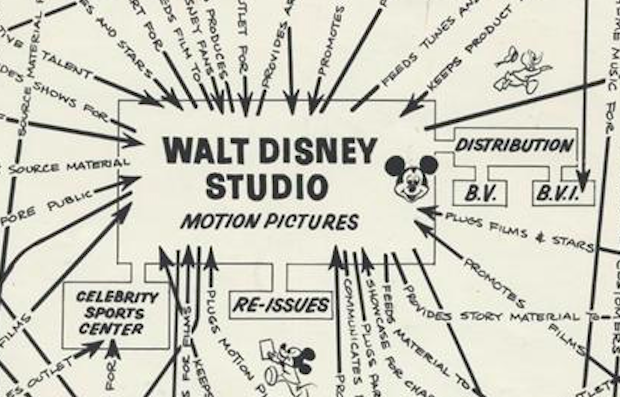

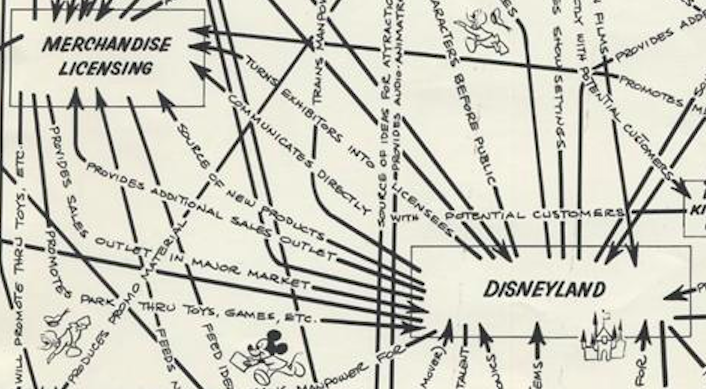

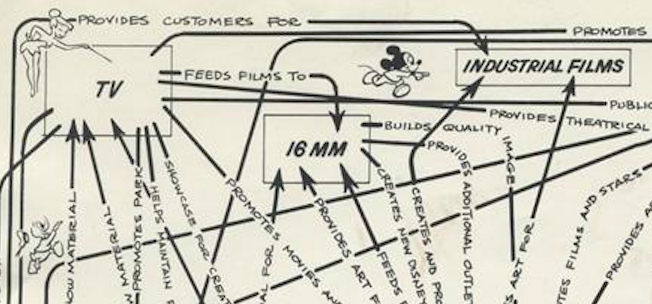

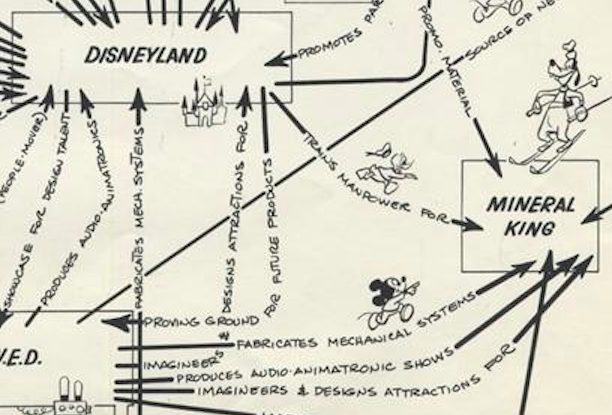

It was already big half a century ago, but not too big to grasp. You can see the whole of the operation laid out in this organizational synergy diagram created by Walt Disney Productions in 1967. Depicting "the many and varied synergistic relationships between the divisions of Walt Disney Productions," the information graphic reveals the links between each division.

Along the arrowheaded lines indicating the flows of manpower, material, and intellectual property, "short textual descriptions show what each division supplies and contributes to the others." The motion picture division "feeds tunes and talent" to the music division, for example, which "promotes premiums for tie-ins" to the merchandise licensing department, which "feeds ideas for retail items" to WED Enterprises (the holding company founded by Walt Disney in 1950), which produces "audio-animatronics" for Disneyland.

Some of the nexuses on the diagram will be as familiar as Mickey Mouse, Goofy, Tinkerbell, and the characters cavorting here and there around it. Others will be less so: the 16-millimeter films division, for instance, which would eventually be replaced by a colossal home-video division (itself surely being eaten into, now, by streaming). The Celebrity Sports Center, an indoor entertainment complex outside Denver, closed in 1994. MAPO refers to a theme-park animatronics unit formed in the 1960s with the profits of Mary Poppins (hence its name) and dissolved in 2012. And as for Mineral King, a proposed ski resort in California's Sequoia National Park, it was never even built.

"The ski resort was one of several ambitious projects that Walt Disney spearheaded in the years before his death in 1966," writes Nathan Masters at Gizmodo. But as the size of the Mineral King plans grew, wilderness-activist opposition intensified. After years of opposition by the Sierra Club, as well as the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act 1970 and the National Parks and Recreation Act of 1978, corporate interest in the project finally fizzled out. Though that would no doubt have come as a disappointment to Walt Disney himself, he might also have known to keep the failure in perspective. As he once said of the empire bearing his name, "I only hope that we never lose sight of one thing — that it was all started by a mouse."

h/t Eli and via Howard Lowery

Related Content:

Disneyland 1957: A Little Stroll Down Memory Lane

How Walt Disney Cartoons Are Made: 1939 Documentary Gives an Inside Look

Walt Disney Presents the Super Cartoon Camera

Disney’s 12 Timeless Principles of Animation

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

A Map of the Disney Entertainment Empire Reveals the Deep Connections Between Its Movies, Its Merchandise, Disneyland & More (1967) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2QzkWzy

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment