Meet Emma Willard, the First Female Map Maker in the U.S., and Her Brilliantly Inventive Maps (Circa 1826)

Americans have never like the word “empire,” having seceded from the British Empire to ostensibly found a free nation. The founders blamed slavery on the British, naming the king as the responsible party. Three of the most distinguished Virginia slaveholders denounced the practice as a “hideous blot,” “repugnant,” and “evil.” But they made no effort to end it. Likewise, according to the Declaration of Independence, the British were responsible for exciting “domestic insurrections among us,” and endeavouring “to bring on the inhabitants of our frontiers, the merciless Indian Savages.”

These denunciations aside, the new country nonetheless began a course identical to every other European world power, waging perpetual warfare, seizing territory and vastly expanding its control over more and more land and resources in the decades after Independence.

U.S. imperial power was asserted not only by force of arms and coin but also through an ideological view that made its appearance and growth an act of both divine and secular providence. We see this view reflected especially in the making of maps and early historical infographics.

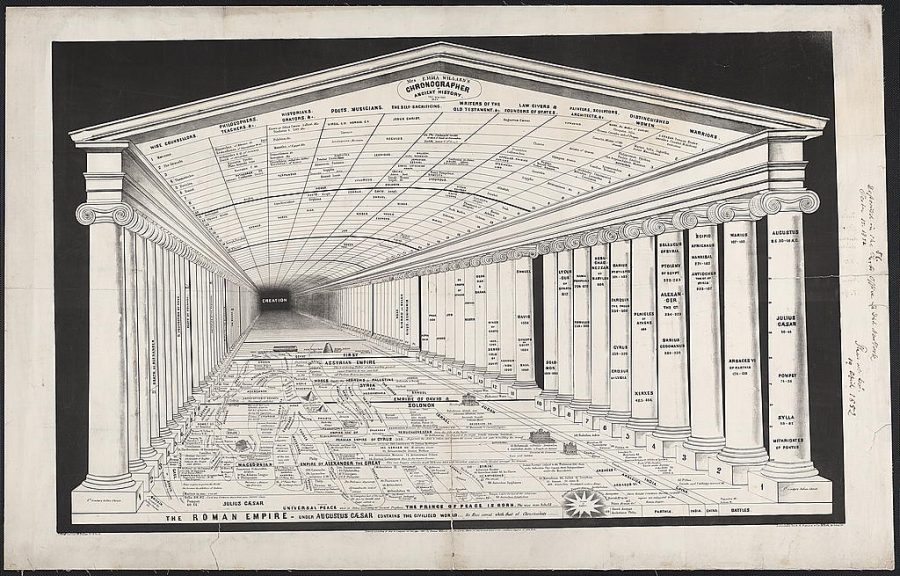

In 1851, three years after war with Mexico had halved that country and expanded U.S. territory into what would become several new states, Emma Willard, the nation’s first female mapmaker, created the “Chronographer of Ancient History” above, a visual representation to “teach students about the shape of historical time,” writes Rebecca Onion at Slate. The Chronographer is a “more specialized offshoot of Willard’s master Temple of Time, which tackled all of history”—or all six thousand years of it, anyway, since “Creation BC 4004.”

Willard made several such maps, illustrating an idea popular among 18th and 19th century historians, and illustrated in many similar ways by other artists: casting history as a succession of great empires, one taking over for another. Viewers of the map stand outside the temple’s stable framing, assured they are the inheritors of its historical largesse. Other visual metaphors told this story, too. Willard, as Ted Widmer points out at The Paris Review. Willard was an “inventive visual thinker,” if also a very conventional historical one.

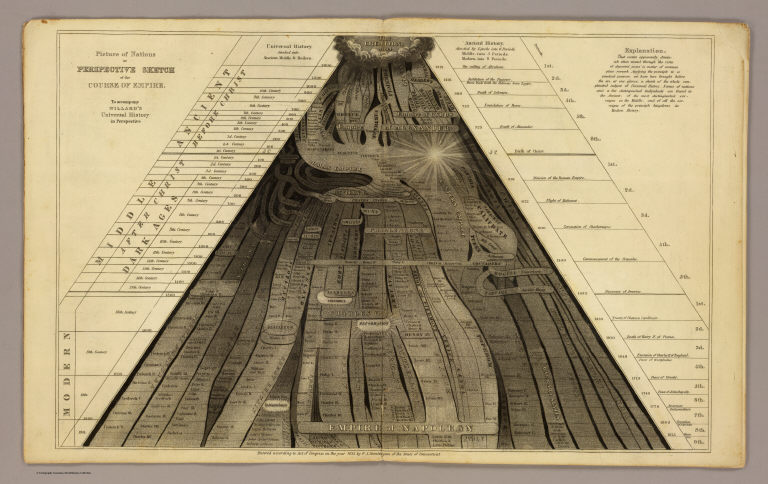

In an earlier map, from 1836, Willard visualized time as a series of branching imperial streams, flowing downward from “Creation.” Curiously, she situates American Independence on the periphery, ending with the “Empire of Napoleon” at the center. The U.S. was both something new in the world and, in other maps of hers, the fruition of a seed planted centuries earlier. Willard’s mapmaking began as an effort to supplement her materials as “a pioneering educator,” founder of the Emma Willard School in Troy, New York, and a “versatile writer, publisher and yes, mapmaker,” who “used every tool available to teach young readers (and especially young women) how to see history in creative new ways.”

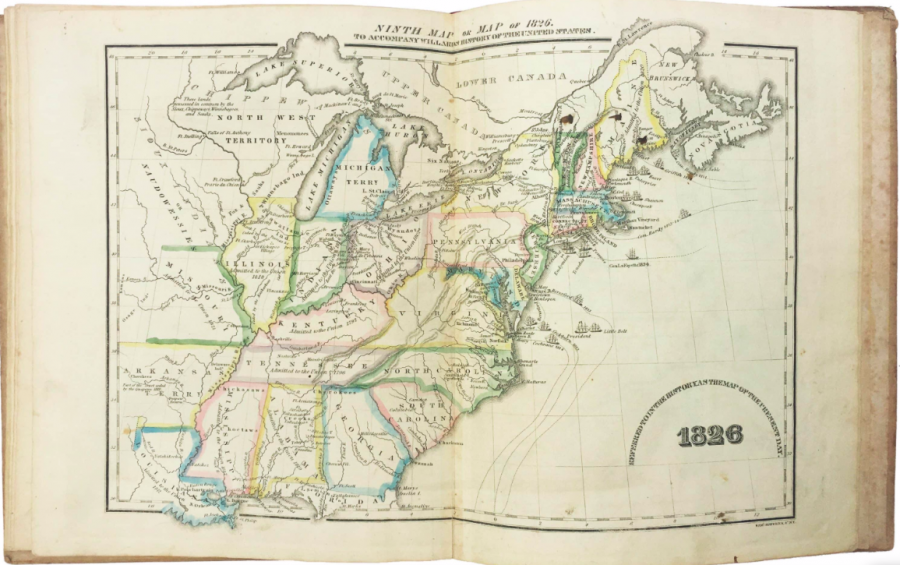

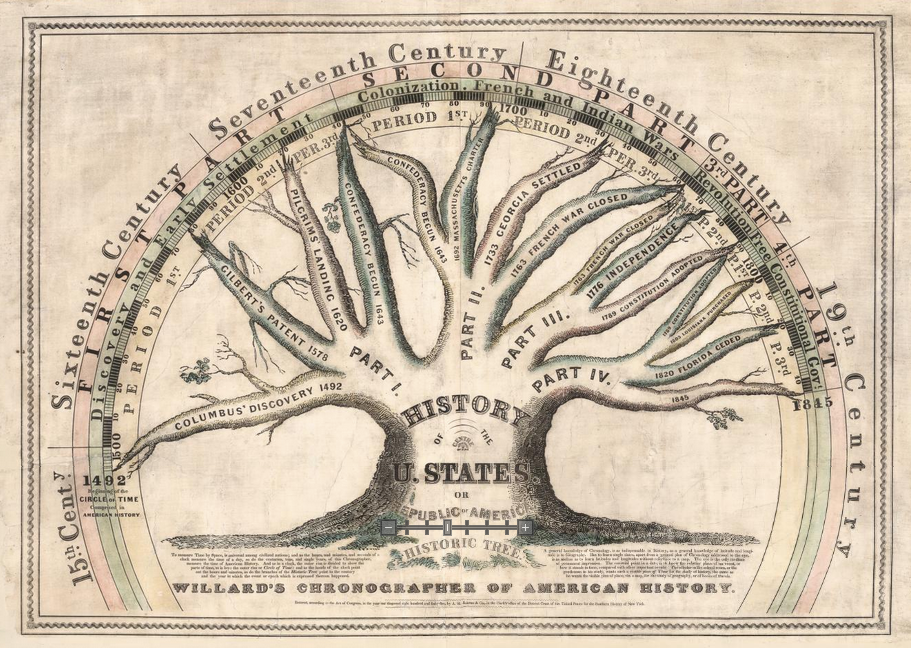

In another "chronographer" textbook illustration, she shows the “History of the U. States or Republic of America” as a tree which had been growing since 1492, though no such place as the United States existed for most of this history. Maps, writes Sarah Laskow at Atlas Obscura, “have the power to shape history” as well as to record it. Willard’s maps told grand, universal stories—imperial stories—about how the U.S. came to be. In 1828, when she was 41, “only slightly older than the United States of America itself," Willard published a series of maps in her History of the United States, or Republic of America.

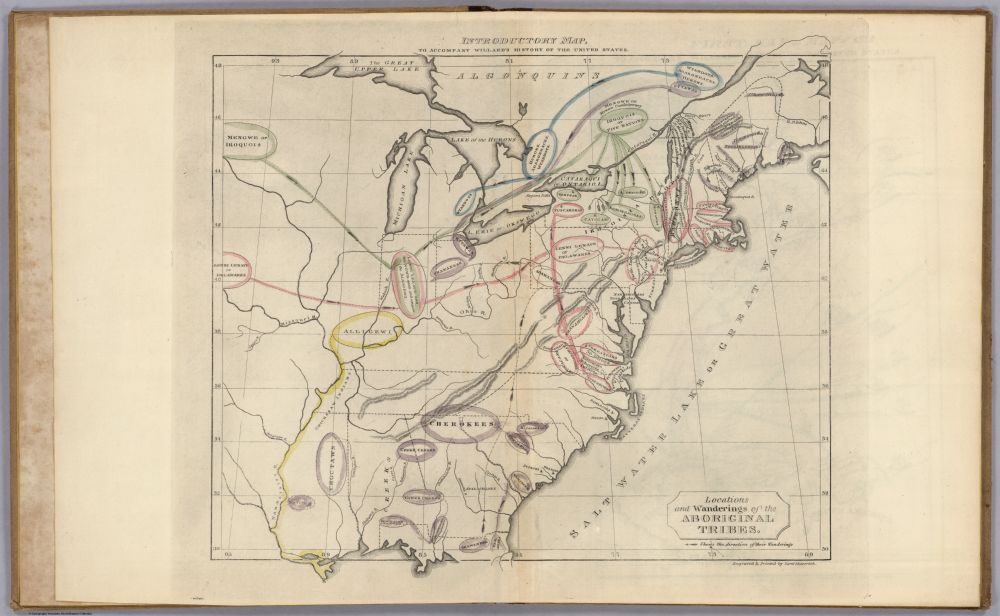

This was “the first book of its kind—the first atlas to present the evolution of America.” Willard’s maps show the movement of Indigenous nations in plates like “Locations and Wanderings of The Aboriginal Tribes… The Direction of their Wanderings,” below—these were part of “a story about the triumph of Anglo settlers in this part of the world. She helped solidify, for both her peers and her students, a narrative of American destiny and inevitability, writes University of Denver historian Susan Schulten. Willard was “an exuberant nationalist,” who generally “accepted the removal of these tribes to the west as inevitable.”

Willard was a pioneer in many respects, including, perhaps, in her adaptation of European neoclassical ideas about history and time in the justification of a new American empire. Her snapshots of time collapse “centuries into a single image,” Schulten explains, as a way of mapping time “in a different way as a prelude to what comes to next.” See many more of Willard’s maps from The History of the United States, or Republic of America, the first historical atlas of the United States, at Boston Rare Maps.

Related Content:

The Atlantic Slave Trade Visualized in Two Minutes: 10 Million Lives, 20,000 Voyages, Over 315 Years

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Meet Emma Willard, the First Female Map Maker in the U.S., and Her Brilliantly Inventive Maps (Circa 1826) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2JgHS1I

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment