Leonardo da Vinci’s Huge Notebook Collections, the Codex Forster, Now Digitized in High-Resolution: Explore Them Online

It may seem like a bizarre question, but indulge me for a moment: could it be possible that the most famous artist of the Renaissance and maybe in all of art history, Leonardo da Vinci, is an underrated figure? Consider the fact that until relatively recently, a huge amount of his work—maybe a majority of his drawings, plans, sketches, notes, concepts, theories, etc.—has been unavailable to all but specialized scholars who could access (and read) his copious notebooks, spanning the most productive period of his career.

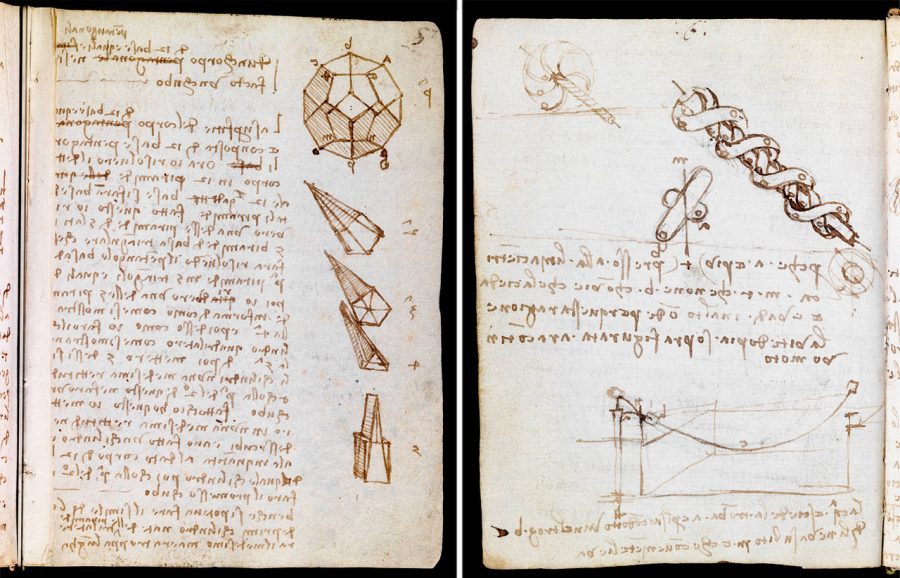

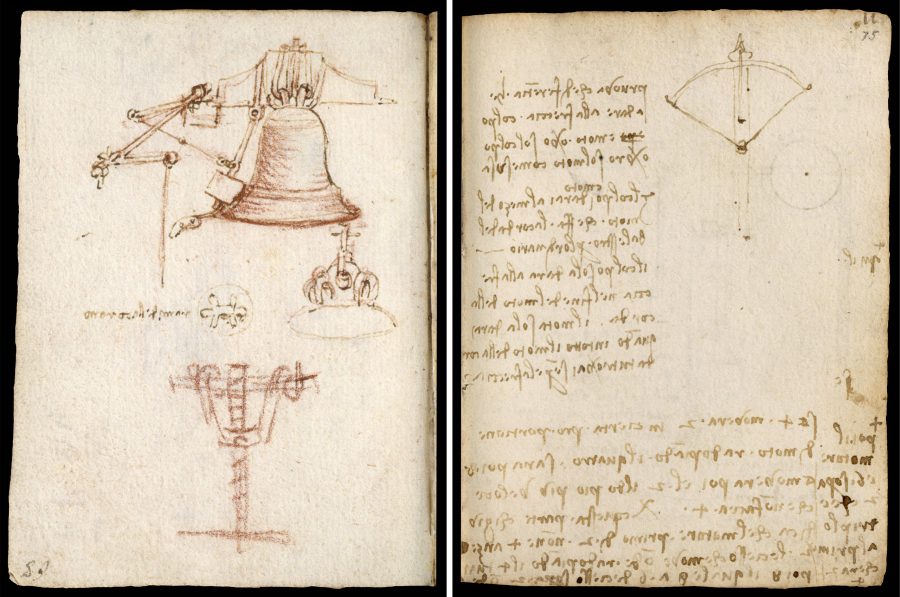

“Leonardo seems to have begun recording his thoughts in notebooks from the mid-1480s,” writes the Victoria & Albert Museum (the V&A), “when he worked as a military and naval engineer for the Duke of Milan. None of Leonardo’s predecessors, contemporaries or successors used paper quite like he did—a single sheet contains an unpredictable pattern of ideas and inventions.” He worked on loose sheets, which were later bound together in books, or codices, by the artists who inherited them. As we have been reporting, these notebook collections have been coming available online in open, high-resolution digital versions.

Now the V&A has announced that all three of its Leonardo codices, called the Forster Codices after the collector who bequeathed them to the museum, are available to view “in amazing detail.” Click here to see Codex Forster 1, Codex Forster 2, and Codex Forster 3. Here we see further evidence that Leonardo was a supreme draughtsman. As Claudio Giorgione, curator at the Leonardo da Vinci National Science and Technology Museum in Milan, points out, “Leonardo was not the only one to draw machines and to do scientific drawings, many other engineers did that,” and many artists as well. “But what Leonardo did better than others is to make a revolution of the technical drawing,” almost defining the field with his meticulous attention to detail.

What’s more, notes University of Oxford Professor Martin Kemp, “while other artists might have been probing some aspects of anatomy—muscles, bones, tendons—Leonardo took the study to a new level.” Such a level, in fact, that he "can be regarded as the father of bioengineering,” argues John B. West in the American Journal of Physiology.

Little attention has been paid to [Leonardo] as a physiologist. But he was an outstanding engineer, and he was one of the first people to apply the principles of engineering to understand the function of animals including humans.

Giorgione warns against seeing Leonardo as a prophetic visionary for his innovations. He was not a man out of time; “the artist engineer is a known figure in Renaissance Italy.” But he perfected the tools and methods of this dual profession with such restless ingenuity and skill that we still find it astonishing over 500 years later. His lengthy explanations of these exceptional technical drawings are written, naturally, in his famous mirror writing.

Of Leonardo’s odd writing system, we may learn something new as well, though we may find this part, at least, a little disappointing. As the V&A points out, his idiosyncratic method might not have been so unique after all, or have been a sophisticated device for Leonardo to hide his ideas from competitors and future curious readers. It might have come about “because he was left-handed and may have found it easier to write from right to left…. Writing masters at the time would have made demonstrations of mirror writing, and his letter-shapes are in fact quite ordinary.”

Nothing else about the man seems to warrant that description. See all three Forster Codices the Victoria & Albert Museum site here: Codex Forster 1, Codex Forster 2, and Codex Forster 3. And see one codex from the collection, as the V&A announced on Twitter, live in person at the British Library’s Leonardo da Vinci: A Mind in Motion exhibit.

Related Content:

Leonardo da Vinci’s Visionary Notebooks Now Online: Browse 570 Digitized Pages

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Leonardo da Vinci’s Huge Notebook Collections, the Codex Forster, Now Digitized in High-Resolution: Explore Them Online is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture http://bit.ly/2ZhCz8o

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment