To be a non-believer in some parts of the world, and in much of Europe for many centuries, means to commit a crime against the state. Even where unbelief goes unpunished by the law, “atheists, agnostics, and other non-believers,” writes Scotty Hendricks at Big Think, “are among the most disliked, untrusted, and misunderstood people.” Identified with Satanists (who are equally misunderstood), non-believers are presumed to be anti-theists, hell bent on destroying, or at least maiming, religion with their know-it-all dogmatism and hatred of different beliefs.

There may be some projection going on here, and maybe it goes both ways at times, though the balance of power, at least in the U.S., decidedly tips in favor of certain dogmatic religions. But as a new whitepaper from the UK group Understanding Unbelief found, in a wide-ranging survey of non-believers in six countries around the world, “popular assumptions about ‘convinced, dogmatic atheists’ do not stand up to scrutiny.” The outlier here is the religiously inflamed U.S. “Although American atheists are typically fairly confident in their views about God, importantly, so too are Americans in general.”

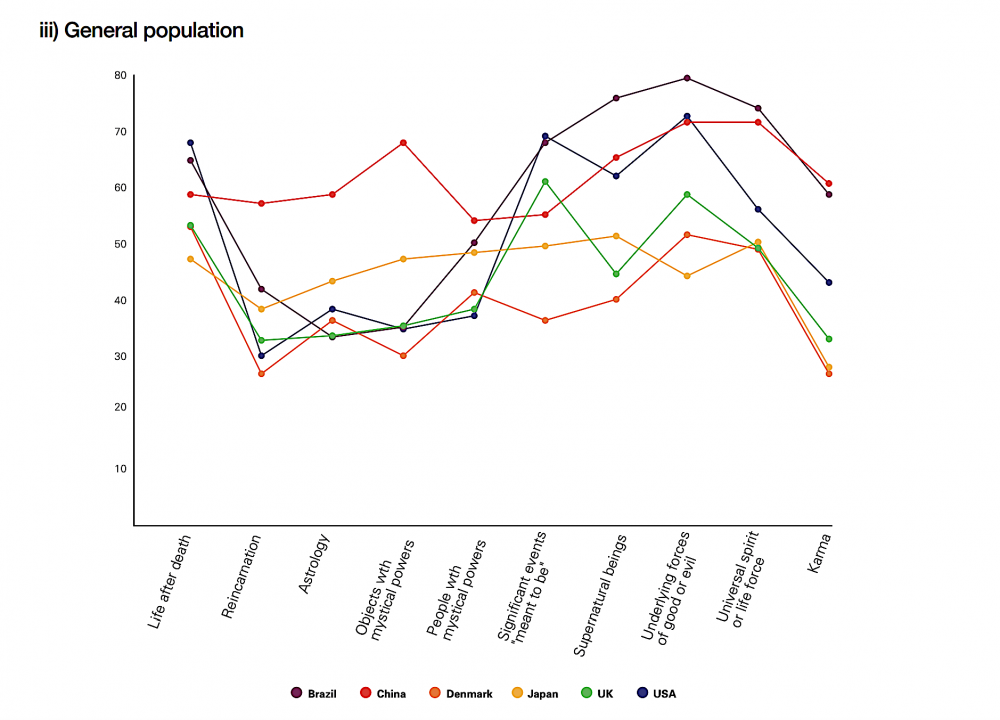

The paper’s authors are professors in theology, psychology, anthropology, and religious studies from four major U.K. Universities. They outline their eight key findings at the outset, then get into specifics about what the data says and how it was obtained, with large, full-color charts and graphs. The study shows more agreement than most of us might assume between the religious and non-religious on “the values most important for ‘finding meaning in the world and your own life.’”

“Family” and “Freedom” ranked highly. “Less unanimously so,” did “’Compassion,’ ‘Truth,’ ‘Nature,’ and ‘Science,’” which may come as little surprise. The social and political identifications of non-believers fluctuate widely between the six countries—Brazil, Denmark, Japan, China, the U.S., and the U.K.—but, “with only a few exceptions, atheists and agnostics endorse the realities of objective moral values, human dignity, and attendant rights, and the ‘deep value’ of nature.”

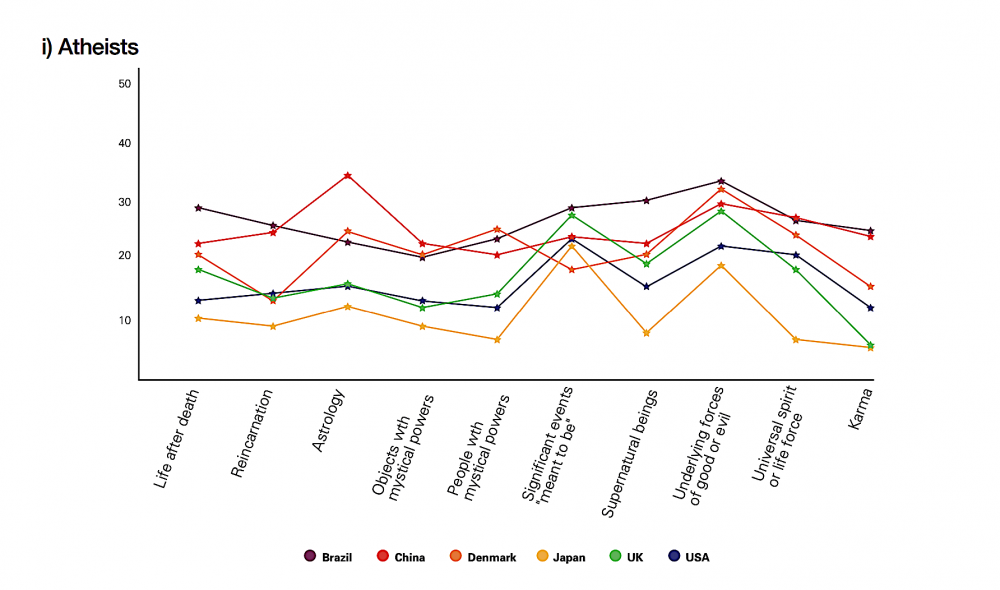

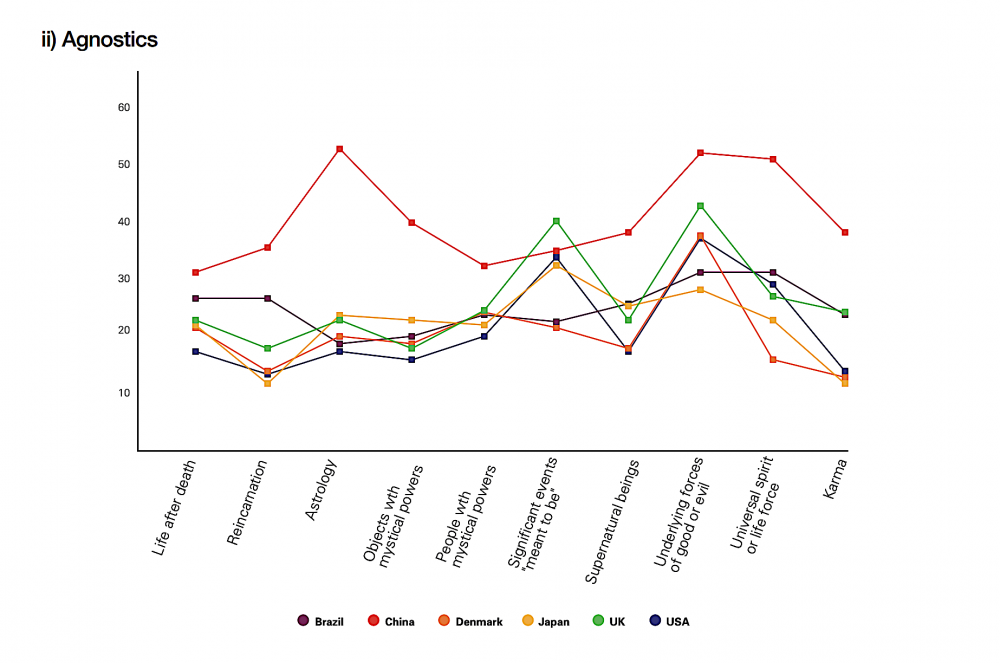

These conclusions should interest non-believers and believers alike in the six countries surveyed, but the most sensational research finding states that “despite rejecting or at least questioning the notion of gods, unbelievers aren’t wholly divorced from superstitious belief,” writes Hendricks. The study’s authors put things in a more measured way: “only minorities of atheists or agnostics in each of our countries appear to be thoroughgoing naturalists,” ruling out the supernatural entirely.

Hendricks lists some examples:

Up to third of self-declared atheists in China believe in astrology. A quarter of Brazilian atheists believe in reincarnation, and a similar number of their Danish counterparts think some people have magical powers.

These findings might be consistent with the study’s methodology, which surveyed people who agreed with either 1. I don’t believe in God [or other divinity or spirit] or 2. I don’t know whether there is a God, and I don’t believe there is any way to find out. Neither of these mutually excludes the à la carte spiritualism of astrology, reincarnation, or magic, a fact that many religious believers cannot wrap their heads around.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, for example, belief in seances, tarot, mesmerism, and other seemingly supernatural phenomena flourished, quite often independently of particular religious belief systems. One of the most rational minds of the time, or the creator of the most rational mind of the time, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, believed in fairies. Pierre Curie “was an atheist who had an enduring, somewhat scientific, interest in spiritualism.”

The study’s findings are “in line,” Hendricks points out, “with previous studies that show non-believers are just as prone to irrational thinking as their religious counterparts.” Significant percentages of atheists and agnostics express some belief in astrology, karma, "a universal spirit or life force," and other supernatural phenomena. Hendricks quotes Michio Kaku’s suggestion that there may be “a gene for superstition, a gene for hearsay, a gene for magic.” I don’t believe geneticists have found such a thing. But culture, at any rate, is not reducible to biology.

The fact that humans see, hear, feel, and believe things that may not actually exist seems to be an evolutionary trait. What may be equally, if not more, interesting is the way those supernatural things, whatever they are, both resemble and vastly differ from each other, their cultural specificities woven inextricably into the texture of language and custom. What and how we think cannot be fully separated either from our genes or from the conceptual apparatus we inherit, and that forms our picture of the world. Read the full Understanding Unbelief study here.

Related Content:

A Visual Map of the World’s Major Religions (and Non-Religions)

Christianity Through Its Scriptures: A Free Course from Harvard University

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Atheists & Agnostics Also Frequently Believe in the Supernatural, a New Study Shows is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture http://bit.ly/2RfrjXb

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment