How Cinemas Taught Early Movie-Goers the Rules & Etiquette for Watching Films (1912): No Whistling, Standing or Wearing Big Hats

I admit, I sometimes pay a premium at a certain dinner theater chain with a lobby-slash-bar designed to look like classic indie video stores of yore. It’s not only the padded recliners and half-decent grub that keeps me coming back. Nope, it’s the rules. Printed on the menu are a list of disruptive behaviors that will get you unceremoniously tossed out—no refunds and no backsies.

I’ve never seen it happen. Given what people put down for tickets, dinner, drinks, and/or a babysitter, it’s unlikely many risk blowing the evening. But knowing that the theater takes silence seriously brings serious moviegoers peace of mind. What is a movie, after all, without the all-important dialogue, music, and sound cues?

Well, it’s silent film. And even then, when movies were sound-tracked with live accompaniment and dialogue appeared on title cards, people worried very much about distractions. It just so happens that talking and texting (obviously) were the least of early audience’s concerns.

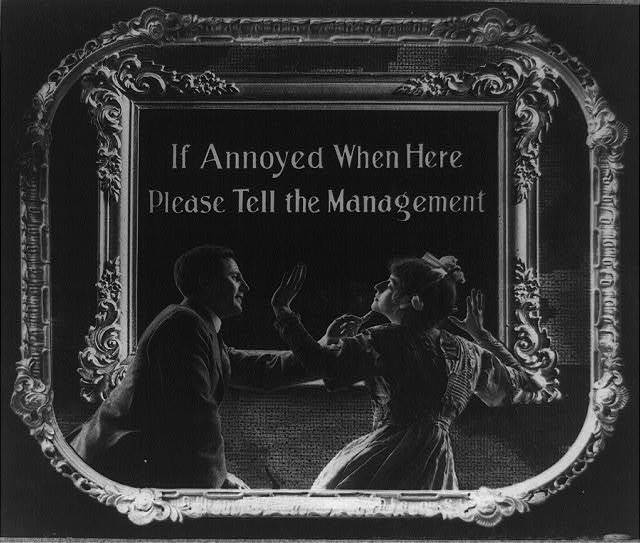

For one thing, the cinema was a place where classes, races, sexes, and ages “mixed much more freely than had been Victorian custom,” notes Rebecca Onion at Slate. There were the usual concerns about corruption of the “delicate sensibilities” of ladies.

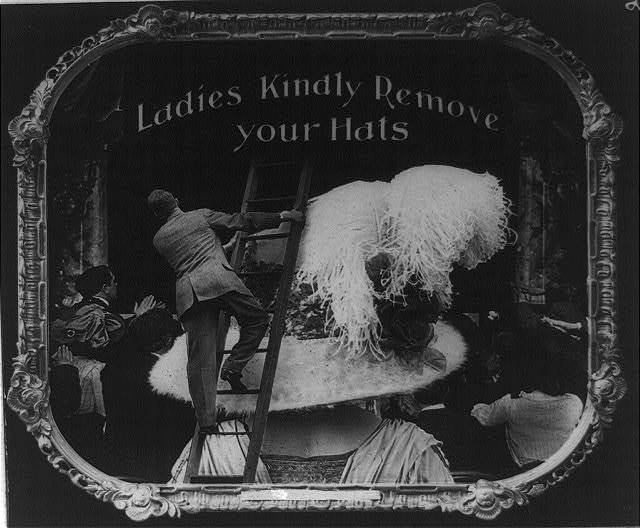

“But female cinema-goers were just as likely to be seen as a problem,” writes Onion, “given their supposed propensity for wearing big hats and chatting.” The melting pot demographic of the nickelodeon could be exhilarating, and audience members found they sometimes lost their inhibitions. “Somehow you enter into the spirt of the thing,” observed author W.W. Winters in 1910. “Don’t you slip away from yourself, lose your reticence, reserve, pride, and a few other things?”

These days we’re accustomed to cramming in elbow-to-elbow next to anyone and everyone, and we mostly heed the onscreen cajoling to put our phones away and keep quiet, even when we aren't quarantined in specialty boutique chains or local arthouse theaters. Then again, if certain behaviors weren’t an issue, there wouldn’t be ads prohibiting them.

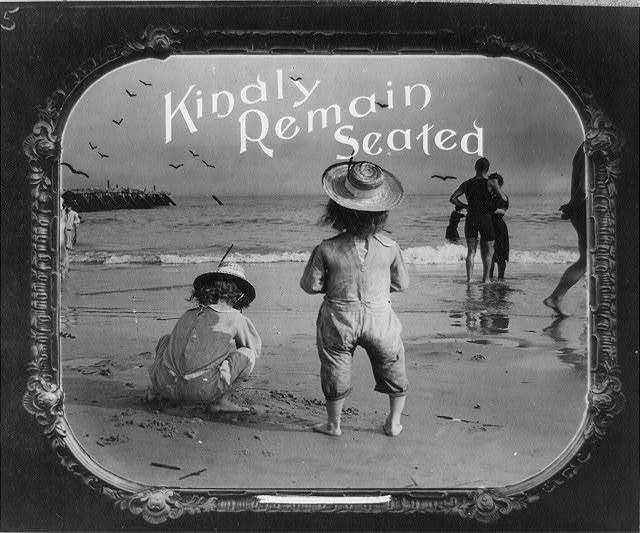

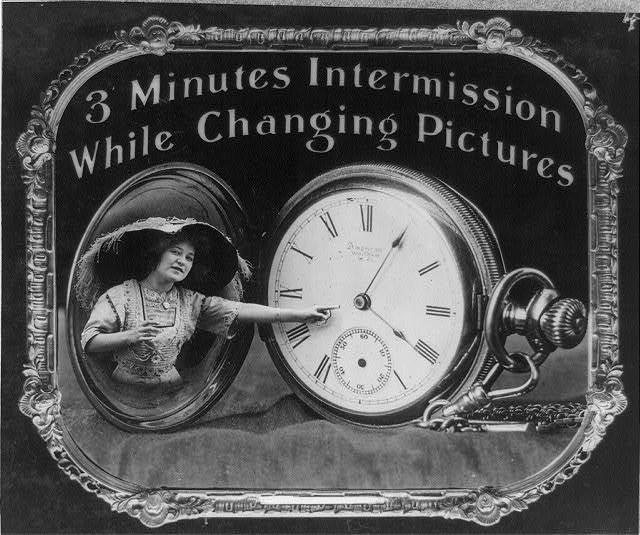

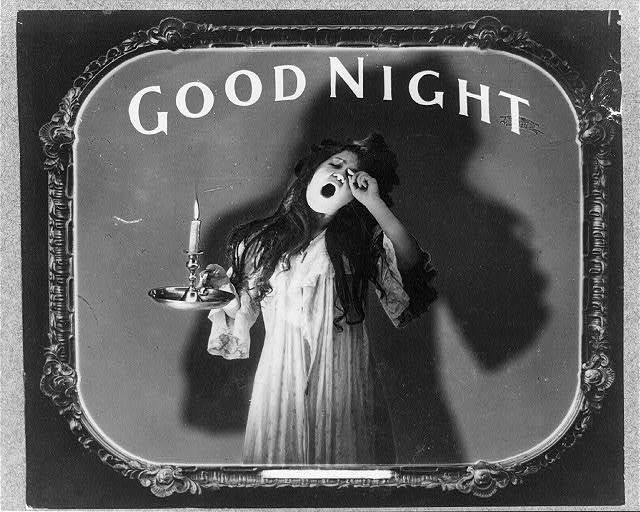

Enormous hats and applause (and applause with things other than hands) may be relics of cinema’s infancy. But swap out those admonitions for others of the smartphone variety and these lantern slides instructing viewers in 1912 about proper movie theater etiquette don’t look so different from today… sort of.

We might want for intermissions to return, especially after the two-hour mark, and wouldn’t it be nice if, instead of keeping us in our seats for post-credit scenes, big blockbuster movies just said “Good Night”? See more of these delightful public service announcements from 1912 nickelodeons at Back Story Radio.

Related Content:

The Art of Creating Special Effects in Silent Movies: Ingenuity Before the Age of CGI

Enjoy the Greatest Silent Films Ever Made in Our Collection of 101 Free Silent Films Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

How Cinemas Taught Early Movie-Goers the Rules & Etiquette for Watching Films (1912): No Whistling, Standing or Wearing Big Hats is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2xf9Ll4

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment