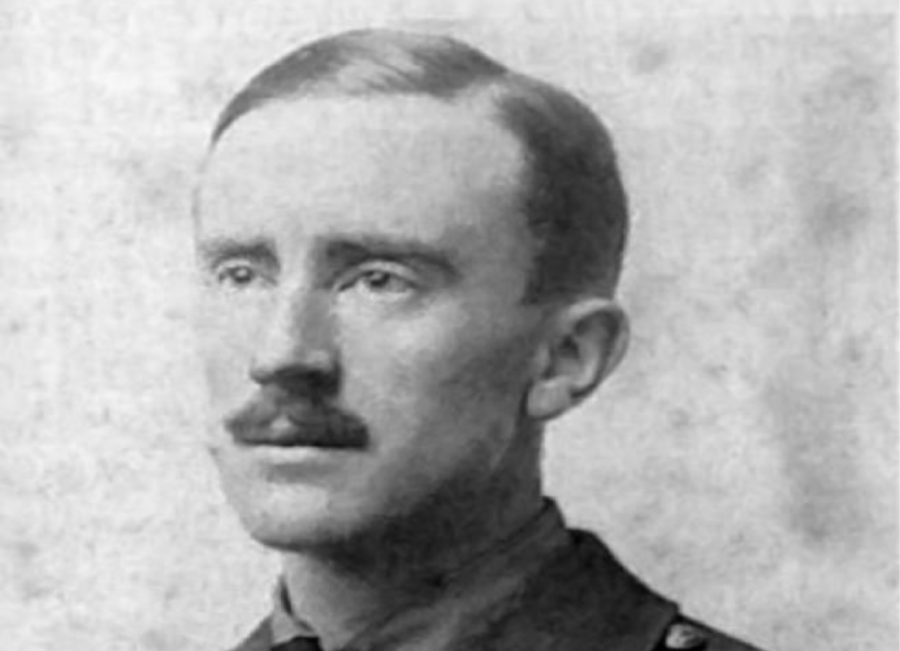

When J.R.R. Tolkien Worked for the Oxford English Dictionary and “Learned More … Than Any Other Equal Period of My Life” (1919-1920)

When J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings appeared in the mid-1950s, its first critical readers held some diverging views on the books’ quality. On the one hand, there was praise for the revival of fantasy for grown-ups, and comparisons to great epics of the past. On the other hand, Tolkien’s prose was excoriated for its wordiness, length, and seemingly inexhaustible obsession with obscurities. Both perspectives seemed to miss something important. Yes, Tolkien drew liberally from epics of the past such as the Norse Sagas and created a world as fully-realized as any in ancient mythology, building in decades what it took centuries to develop.

It’s also true that Tolkien wrote in a thoroughly unusual way — unfamiliar as he was with the conventions of contemporary literary writing. But his style did not only derive from his work as a scholar of Anglo-Saxon literature. For all of the discussion of Tolkien’s encyclopedic technique, no one seemed to note at the time that the author had, in fact, invented for himself (with apologies to James Joyce) a new genre and way of writing, a kind of etymological fantasy, a kind of writing he learned while working on the Oxford English Dictionary, that august catalogue of the English language that first appeared in full in 1928, in ten volumes after fifty years of work.

The Oxford English Dictionary (OED) remains an indispensable reference for scholars of language and literature, but it is not itself a typical academic text. It is a compendium, a miscellany, a descriptive map and timeline tracking how English evolves; it is the ultimate reference work, a work of philology, a discipline that had fallen out of fashion by the time of The Lord of the Rings. The first edition of the OED, begun in 1878 (five years into the proposed timeline, the editors had only reached the word “ant”), contained around 400,000 words. Between the years 1919 and 1920, Tolkien was responsible for the words between waggle and warlock. He would later say he “learned more in those two years than in any other equal period of my life.”

The OED establishes linguistic histories by citing a word’s appearances in literature and popular press over time, tracing derivations from other languages, and tracing the evolution, and extinction, of words and meanings. After his return from World War I, the future novelist found himself working under founding co-editor Henry Bradley, laboring away on words like walnut, walrus, and wampum, which “seem to have been assigned to Tolkien because of their particularly difficult etymologies,” notes the OED blog. These entries would later be singled out by Bradley as “containing ‘etymological facts or suggestion not given in other dictionaries.'”

The experience as an OED lexicographer prepared Tolkien for his lifelong career as a philologist. It also informed his literary technique, argue Peter Gilliver, Jeremy Marshall, and Edmund Weiner, the authors of Ring of Words: Tolkien and the Oxford English Dictionary and former OED editors, all. The authors show how Tolkien drew the language of his books directly from his etymological research. For example, “for decades it was assumed that he was being characteristically modest” when he declined to claim credit for the invention of the word “hobbit.” As it turned out, “an obscure list of mythical beings, published in 1895” came to light in 1977, including the word “‘hobbits’, along with such other irresistible creatures as ‘boggleboes’ and gallytrots,” writes Kelly Grovier at The Guardian.

Tolkien’s relationship to etymology in The Hobbit, The Lord of the Rings, and every other lengthy piece of writing Middle Earth-related goes far beyond digging up obscure words or coining new ones. He learned to think like a lexicographer. As the authors write, “in describing his own creative processes, Tolkien often comments on how the contemplation of an individual word can be the starting point for an adventure in imagination — and contemplating individual words is precisely what lexicographers do.” Tolkien’s boundless curiosity about the roots of language led him to “invent everything,” writes Tolkien critic John Garth, “from star mariners to calendars, flowers, cities, foodstuffs, writing systems and birthday customs, to mention just a few of the eclectic features of Middle-earth.”

Decades after Tolkien’s first association with the OED, he would become involved again with the publication in 1969 when the editor of the dictionary’s Supplement, his former student Robert Burchfield, asked for comments on the entry for “Hobbit.” Tolkien offered his own definition for just one of the many Tolkienian words that would eventually make into the OED (along with mathom, orc, mithril, and balrog). Burchfield published Tolkien’s definition almost exactly as written:

In the tales of J. R. R. Tolkien (1892-1973): one of an imaginary people, a small variety of the human race, that gave themselves this name (meaning ‘hole-dweller’) but were called by others halflings, since they were half the height of normal men.

Learn more about Tolkien’s work on the Oxford English Dictionary‘s first edition in this article by Peter Gilliver and pick up a copy of Ring of Words here.

Related Content:

Discover J.R.R. Tolkien’s Personal Book Cover Designs for The Lord of the Rings Trilogy

Discover J.R.R. Tolkien’s Little-Known and Hand-Illustrated Children’s Book, Mr. Bliss

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

When J.R.R. Tolkien Worked for the Oxford English Dictionary and “Learned More … Than Any Other Equal Period of My Life” (1919-1920) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2YEwRCn

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment