A 13th-Century Cookbook Featuring 475 Recipes from Moorish Spain Gets Published in a New Translated Edition

Some of the distinctiveness of Spain as we know it today comes as a legacy of the period from 700 to 1200, when most of it was under Muslim rule. The culture of Al-Andalus, as the Islamic states of modern-day Spain and Portugal were then called, survives most visibly in architecture. But it also had its own cuisine, developed by not just Muslims, but by Christians and Jews as well. Whatever the dietary restrictions they individually worked under, “cooks from all three religions enjoyed many ingredients first brought to the Iberian peninsula by the Arabs: rice, eggplants, carrots, lemons, sugar, almonds, and more.”

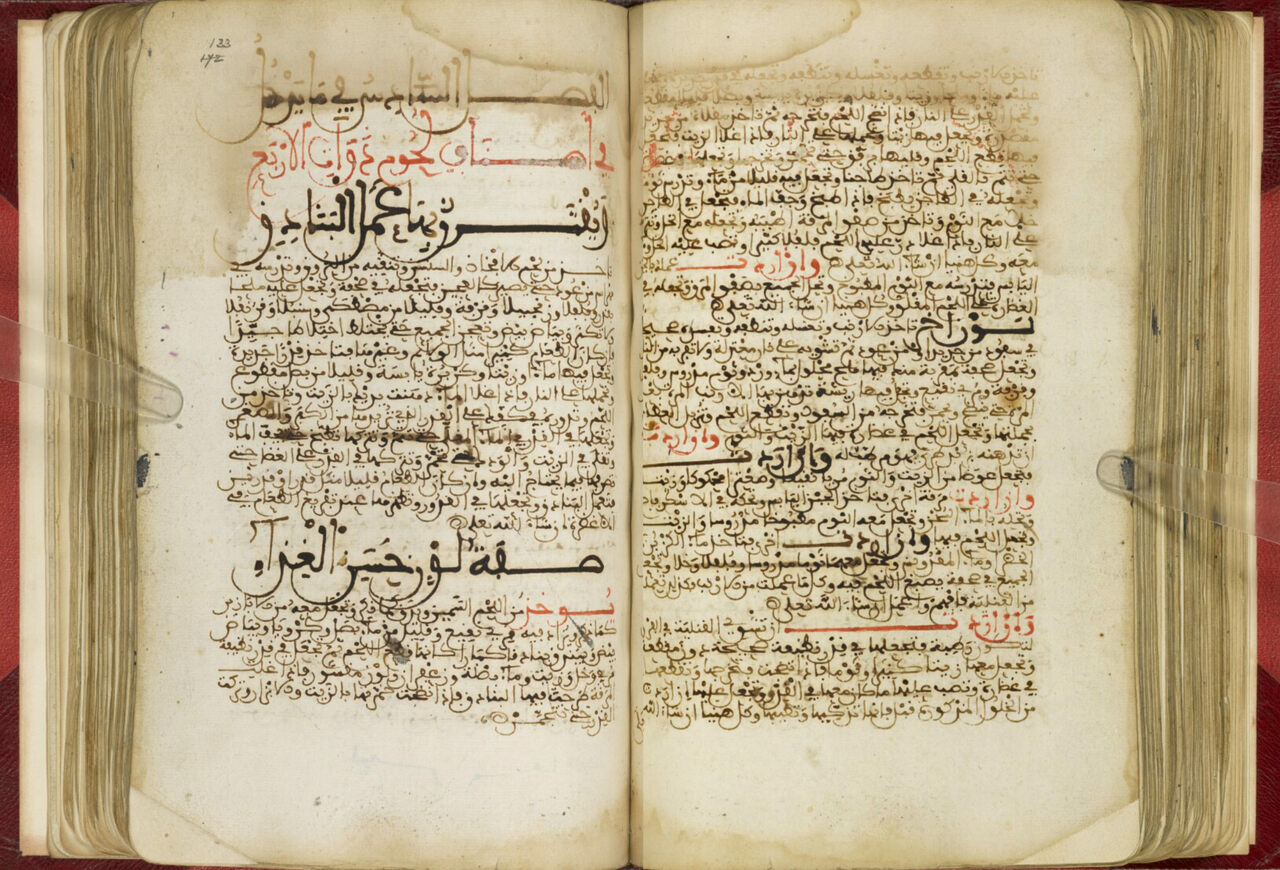

So writes Atlas Obscura’s Tom Verde in an article occasioned by the publication of a thirteenth-century Moorish cookbook. Fid?a?lat al-Khiwa?n fi? T?ayyiba?t al-T?a?a?m wa-l-Alwa?n, or Best of Delectable Foods and Dishes from al-Andalus and al-Maghrib had long existed only in bits and pieces. A “maddeningly incomplete carrot recipe, along with missing chapters on vegetables, sauces, pickled foods, and more, left a gaping hole in all existing editions of the text, like an empty aisle in the grocery store.” But in 2018, British Library curator of Arabic scientific manuscripts Dr. Bink Hallum happened upon a nearly complete fifteenth- or sixteenth-century copy of the Fid?a?la within a manuscript on medieval Arab pharmacology.

The Fid?a?la itself dates to around 1260. It was composed in Tunis by Ibn Raz?n al-Tuj?b?, “a well-educated scholar and poet from a wealthy family of lawyers, philosophers, and writers. As a member of the upper class, he enjoyed a life of leisure and fine dining which he set out to celebrate in the Fid?a?la.” The Christian Reconquista had already put a bitter end to all that leisure and fine dining, and it was in relatively hardscrabble African exile that al-Tuj?b? wrote this less as a cookbook than as “an exercise in culinary nostalgia, a wistful look back across the Strait of Gibraltar to the elegant main courses, side dishes, and desserts of the author’s youth, an era before Spain’s Muslims and Jews had to hide their cultural cuisines.”

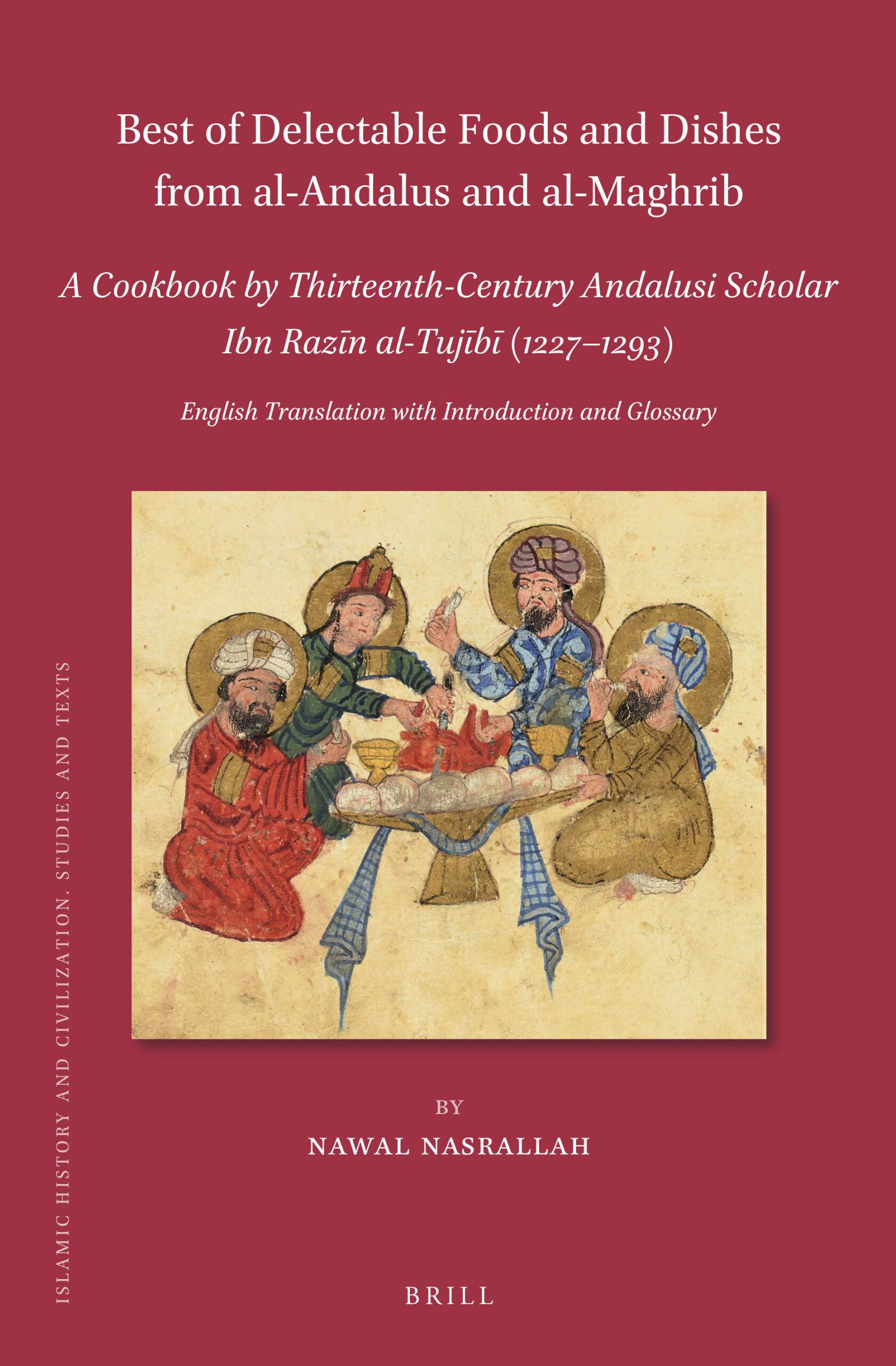

That description comes from food historian Nawal Nasrallah, translator of the complete Fid?a?la into an English edition published last month by Brill. In some of its sections al-Tuj?b? covers breads, vegetables, poultry dishes, and “meats of quadrupeds”; in others, he goes into detail on stuffed tripe, “edible land snails,” and techniques for “remedying overly salty foods and raw meat that does not smell fresh.” (The book includes 475 recipes in total.) Though much in the Moorish diet is a far cry from that of the majority in modern English-speaking countries, interest in historical gastronomy has been on the rise in recent years. And as even those separated from al-Tuj?b? by not just culture but seven centuries’ worth of time know, whatever your reasons for leaving a place, you soon long for nothing as acutely as the food — and that longing can motivate impressive achievements.

Related Content:

What Did People Eat in Medieval Times? A Video Series and New Cookbook Explain

An Archive of 3,000 Vintage Cookbooks Lets You Travel Back Through Culinary Time

A Database of 5,000 Historical Cookbooks — Covering 1,000 Years of Food History — Is Now Online

Discover Japan’s Oldest Surviving Cookbook Ryori Monogatari (1643)

Download 10,000+ Books in Arabic, All Completely Free, Digitized and Put Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

A 13th-Century Cookbook Featuring 475 Recipes from Moorish Spain Gets Published in a New Translated Edition is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3AWbmuv

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment