Two centuries ago, Haiti, “then known as Saint-Domingue, was a sugar powerhouse that stood at the center of world trading networks,” writes Philippe Girard in his history of the Haitian war for independence. “Saint-Domingue was the perle de Antilles… the largest exporter of tropical products in the world.” The island colony was also at the center of the trade in plants that drove the scientific revolution of the time, and many a naturalist profited from the trade in slaves and sugar, as did planter, “physician, botanist, and inadvertent historiographer of the Haitian Revolution” Michel Etienne Descourtilz, the Public Domain Review writes.

Descourtilz’ 1809 Voyages d’un naturaliste “chronicles, among other adventures, a trip from France to Haiti in 1799 in order to secure his family’s plantations.” Instead, he was arrested and conscripted as a doctor under Jean-Jacques Dessalines.

The experience did not change his view that the island should be reconquered, though he did admit “the germ” of rebellion “must secretly have existed everywhere there were slaves.” Decourtilz chiefly spent his time, while not attending to those wounded by Napoleon’s army, collecting plants between Port-au-Prince and Cap-Haïtien.

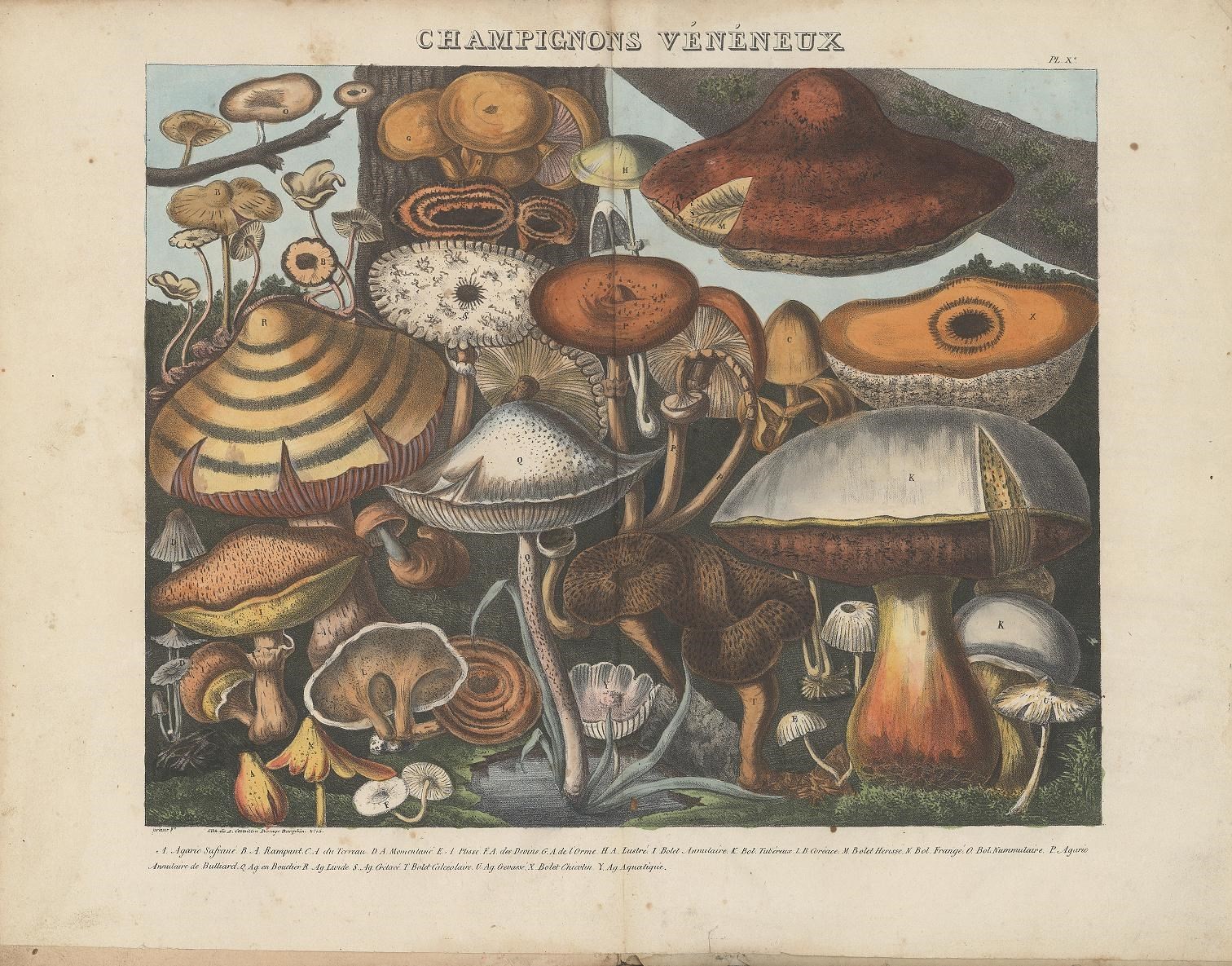

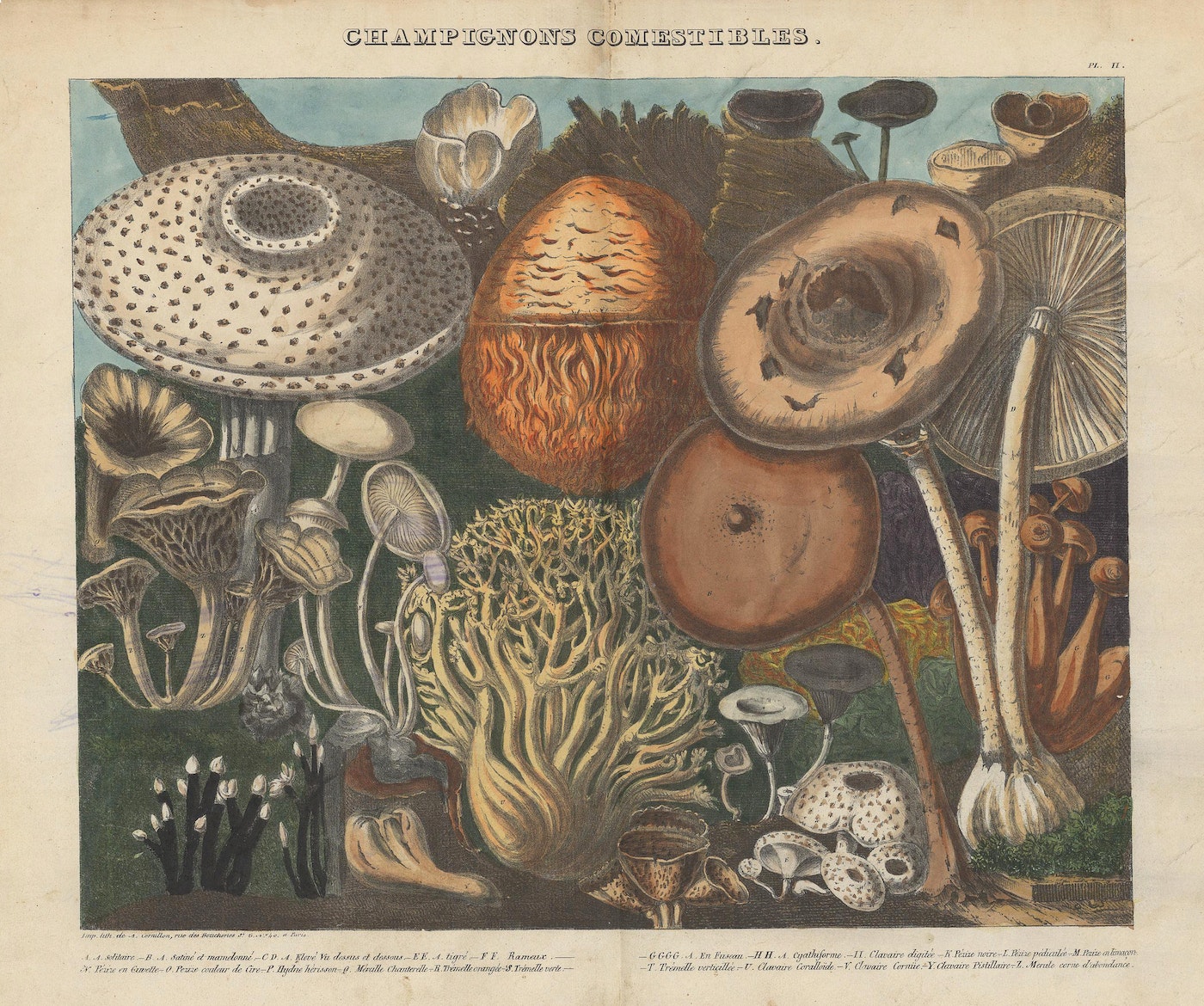

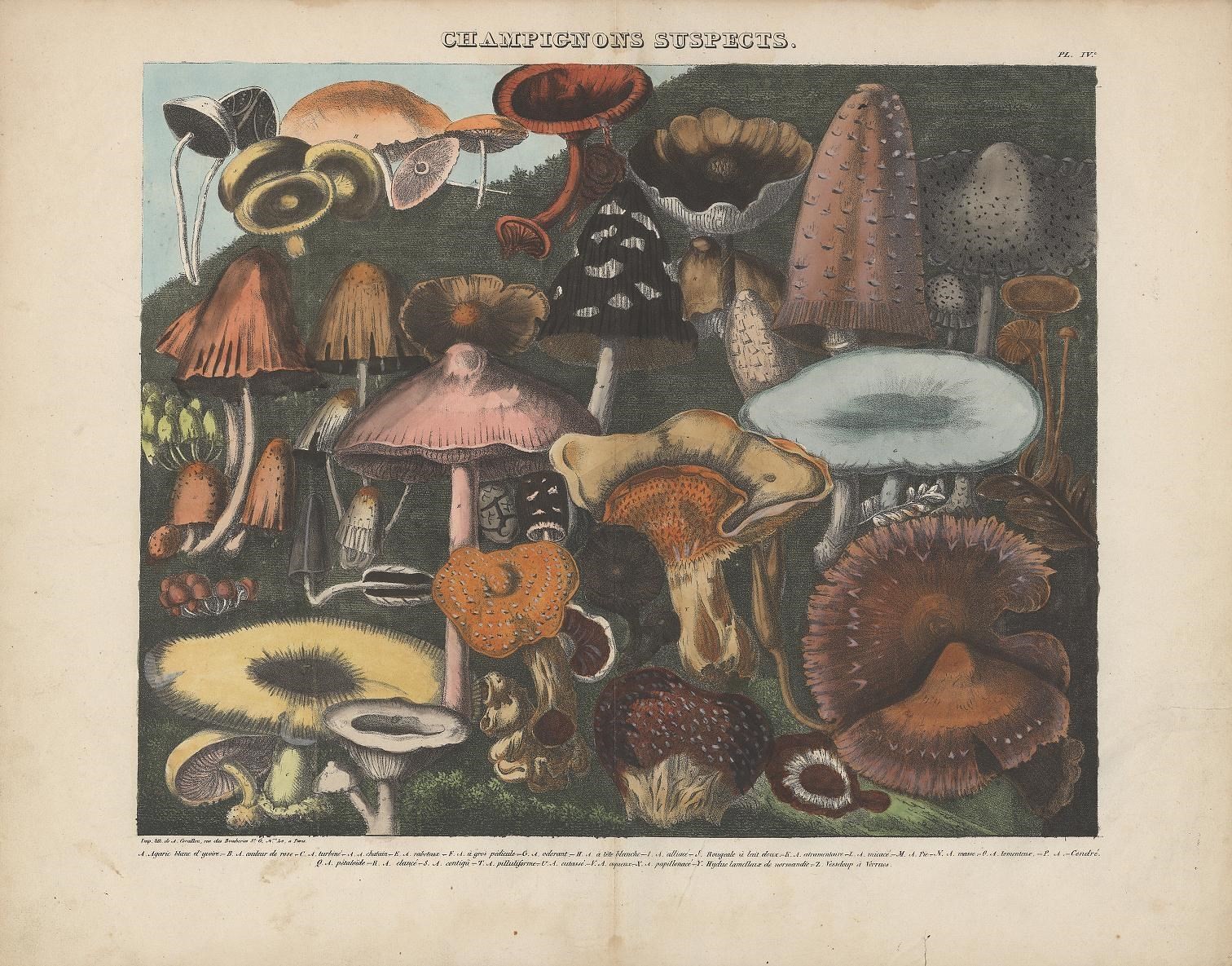

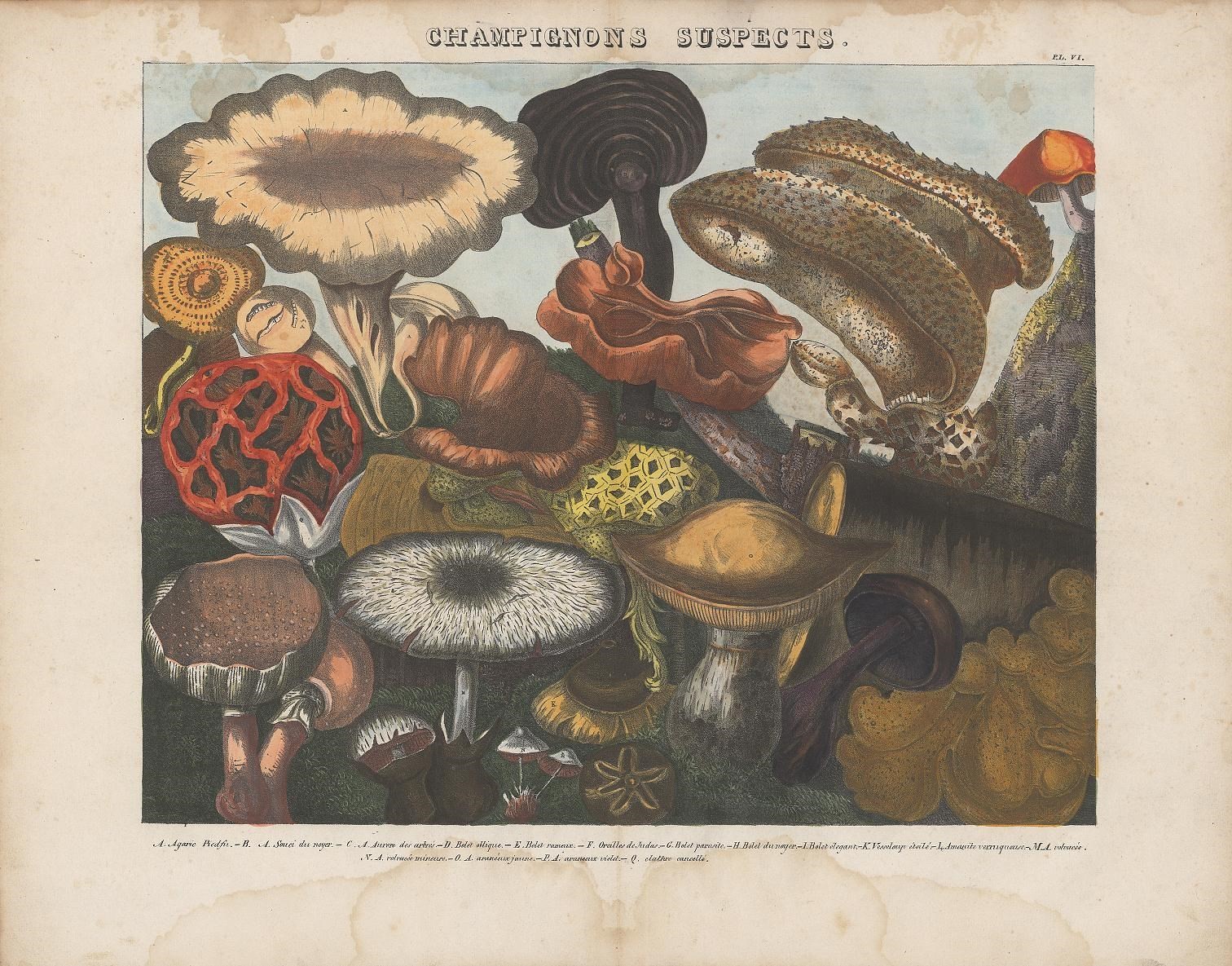

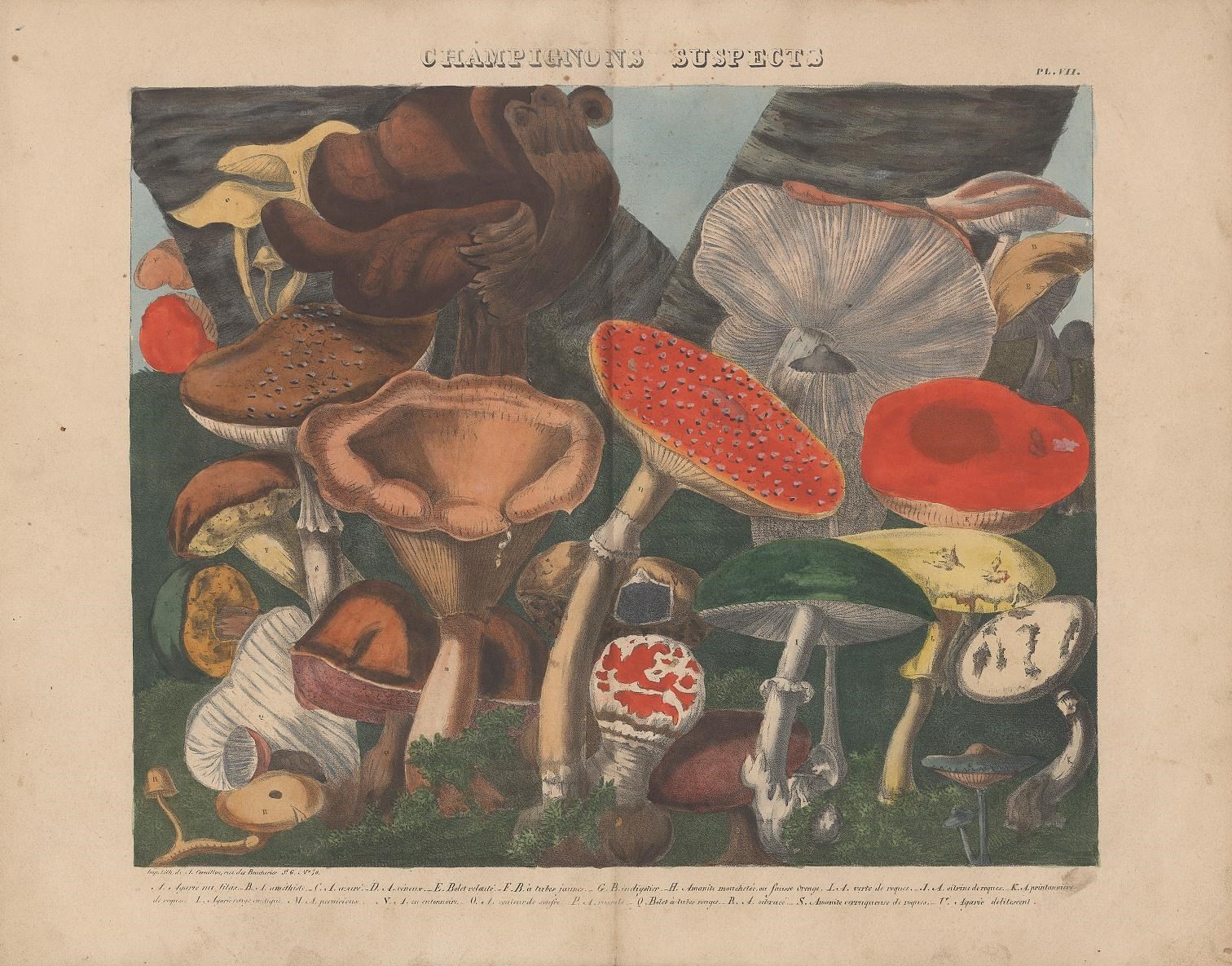

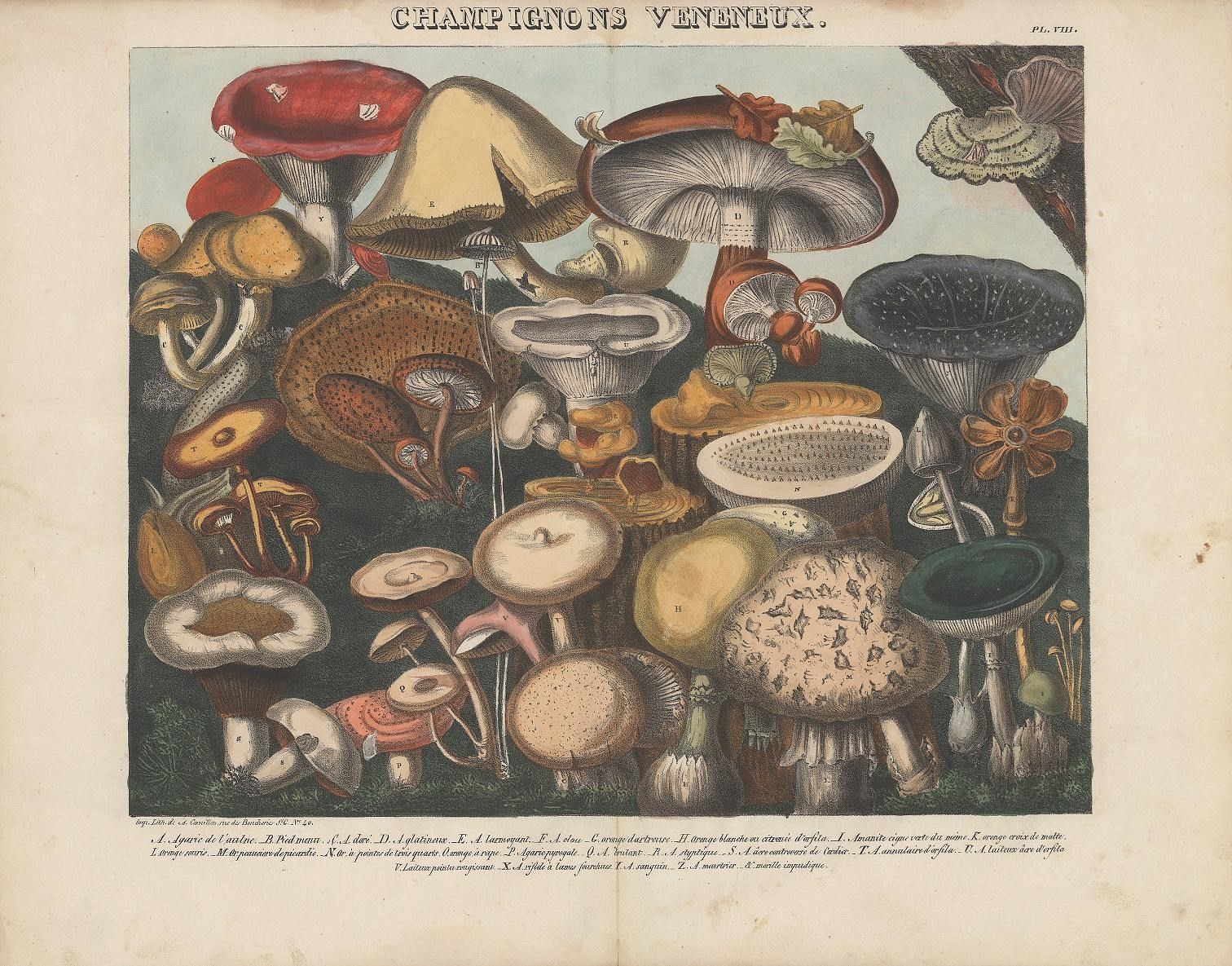

In the dense tropical growth along the Artibonite river, now part of the border between Haiti and Cuba, Decourtilz learned much about the plant world — and maybe learned from some Haitians who knew more about the island’s flora than the Frenchman did. Rescued in 1802, Decourtilz returned to France with his plants and began to compile his research into taxonomic books, including Flores pittoresque et medicale des Antilles, in eight volumes, and a later, 1827 work entitled Atlas des champignons: comestibles, suspects et vénéneux, or “Atlas of mushrooms: edible, suspect and poisonous.”

As the title makes clear, sorting out the differences between one mushroom and another can easily be a matter of life and death, or at least serious poisoning. “Fly agaric, for example,” writes the Public Domain Review, “can resemble edible species of blushers.” Consumed in small amounts, it might cause hallucinations and euphoria. Larger doses can lead to seizures and coma. One can imagine the numbers of colonists in the French Caribbean who either had very bad trips or were poisoned or killed by unfamiliar plant life. Just last year alone in France, hundreds were poisoned from misidentified mushrooms.

To guide the mushroom hunter, cook, and eater, Decourtiliz’s book featured these rich, colorful lithographs here by artist A. Cornillon (which may remind us of the proto-psychedelic scientific art of Ernst Haeckel). He alludes to the great dangers of wild mushrooms in a dedication to “S.A.R., Duchesse de Berry” and promises his guide will prevent “mortal accidents” (those which “frequently occur among the poor.”) Descourtilz offers his guide, accessible to all, he writes, out of a devotion to the alleviation of human suffering. Read his Atlas of Mushrooms, in French at the Internet Archive, and see more of Cornillon’s illustrations here.

Related Content:

1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The Beautifully Illustrated Atlas of Mushrooms: Edible, Suspect and Poisonous (1827) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3pjUUSs

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment