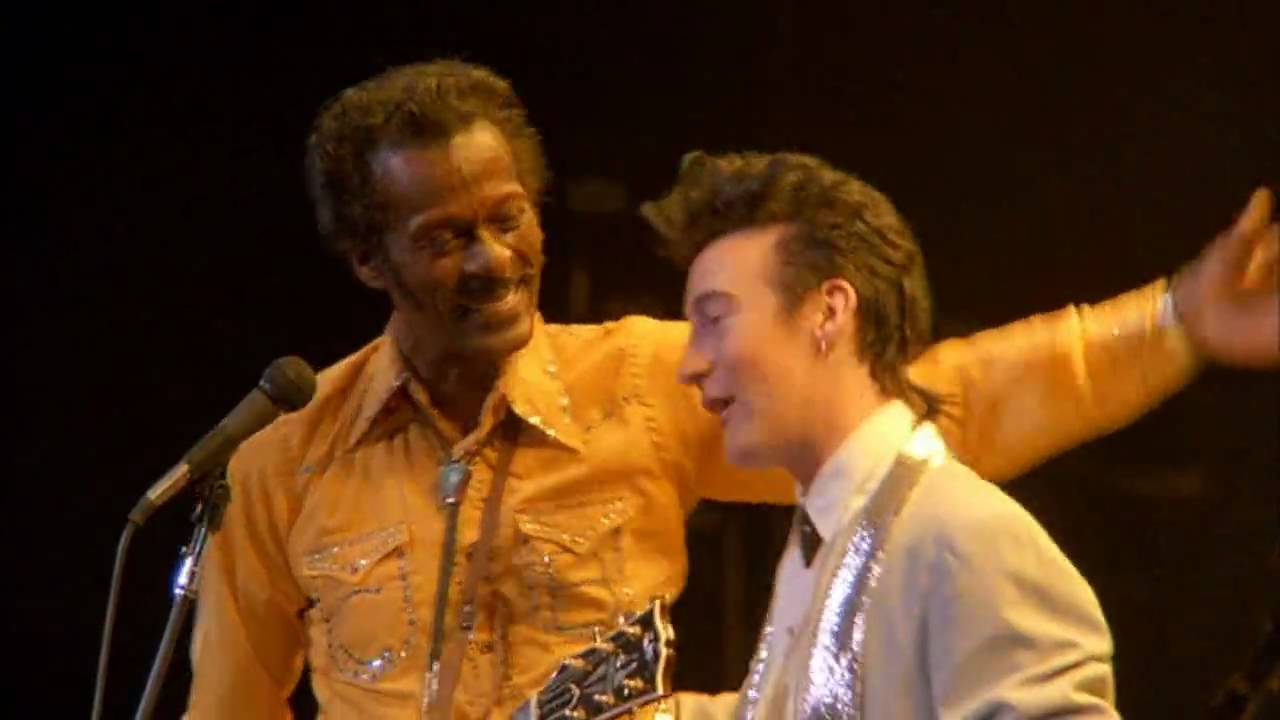

“If you had tried to give rock and roll another name, you would call it Chuck Berry,” says John Lennon by way of introduction to his hero in the clip above from The Mike Douglas Show. The two perform Berry’s “Memphis, Tennessee” and “Johnny B. Goode” (with Lennon’s backing band, Elephant’s Memory, and unwelcome discordant backing vocals from Yoko). The moment was a major highlight of Lennon’s post-Beatles’ career. The year was 1972, and Lennon and Yoko Ono had taken over Douglas’ show for the week, booking such guests as Ralph Nader, Jerry Rubin, and then Surgeon General Dr. Jesse Steinfeld. Douglas called it “probably the most memorable week I did in all my 20-something years on air,” Guitar World notes. Lennon used it as the opportunity to finally meet, and jam out, with his idol.

Berry wasn’t just a major inspiration for the young Lennon; “From his songwriting and lyrics, to his guitar playing and stage antics, perhaps nobody else short of Elvis Presley was as influential on [all] the young Beatles as Chuck Berry,” writes Beatles scholar Aaron Krerowicz, listing “at least 15” of Berry’s songs the band covered (as either the Quarrymen or the Beatles). Paul McCartney credits Berry for the Beatles’ very existence. They were fans, he wrote in tribute after Berry’s death, “from the first minute we heard the great guitar intro to ‘Sweet Little Sixteen.’” But it wasn’t only Berry’s playing that hooked them: “His stories were more like poems than lyrics…. To us he was a magician.”

McCartney first pointed out the similarities between Lennon’s “Come Together” (originally penned as a campaign song for Timothy Leary’s run against Ronald Reagan for the governorship of California) and Berry’s 1956 “You Can’t Catch Me,” he tells Barry Miles in Many Years From Now. “John acknowledged it was rather close to it,” says Paul, “so I said, ‘Well, anything you can do to get away from that.’” Despite the resulting “swampy” tempo, Berry’s legal team still sued over the lyric “here comes old flat-top,” a direct lift from Berry’s song. In an out-of-court settlement, Lennon agreed to record even more of Berry’s tunes. “You Can’t Catch Me” appears on Lennon’s 1975 album of classic covers, Rock ‘n’ Roll.

This legal tussle aside, there was no beef between the two. The appearance on Douglas’ show proved to be a huge boost for Berry, who revitalized his career that year with the suggestive, controversial “My Ding-a-Ling,” his biggest-selling hit, and — in an ironic twist — originally a goofy novelty song composed and recorded by Dave Bartholomew 20 years earlier. When asked by Douglas, however, what drew him to Berry’s music, Lennon echoes McCartney: “[Berry] was writing good lyrics and intelligent lyrics in the 1950s when people were singing ‘Oh baby, I love you so.’ It was people like him that influenced our generation to try and make sense out of the songs rather than just sing ‘do wah diddy.’”

Lennon wasn’t above covering Gene Vincent’s “Be-Bop-a-Lula” a few years later, and the Beatles themselves mixed intelligent narrative songwriting with healthy doses of pop nonsense — patterning themselves after the man Lennon called “my hero, the creator of Rock and Roll.” A few years after Lennon’s 1980 death, Berry returned the compliment, calling Lennon “the greatest influence in rock music” before bringing Julian Lennon onstage and exclaiming, “ain’t he like his pa!”

The year was 1986 and the occasion was Berry’s 60th birthday concert. After their performance of “Johnny B. Goode,” Berry leaned over to Julian and said, “Tell papa hello. I’ll tell you what he says. I’ll see him.” It’s a bittersweet moment. Little, I guess, did Berry suspect that he would rock on for another 30 years, releasing his final, posthumous album in 2017 after his death at age 90.

Related Content:

Chuck Berry Takes Keith Richards to School, Shows Him How to Rock (1987)

Hear the Original, Never-Heard Demo of John Lennon’s “Imagine”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

John Lennon Finally Meets & Jams with His Hero, Chuck Berry (1972) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3vzHKCd

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment