Behold the Photographs of John Thomson, the First Western Photographer to Travel Widely Through China (1870s)

In the early 1860s, a few Westerners had seen China — but nearly all of them had seen it for themselves. The still-new medium of photography had yet to make images of everywhere available to viewers everywhere else, which meant an opportunity for traveling practitioners like John Thomson. “The son of a tobacco spinner and shopkeeper,” says BBC.com, ” he was apprenticed to an Edinburgh optical and scientific instrument manufacturer where he learned the basics of photography.”

In 1862 Thomson sailed from Leith “with a camera and a portable dark room. He set up in Singapore before exploring the ancient civilizations of China, Thailand — then known as Siam — and Cambodia.” It is for his extensive photography of China in the late 1860s and early 1870s that he’s best known today.

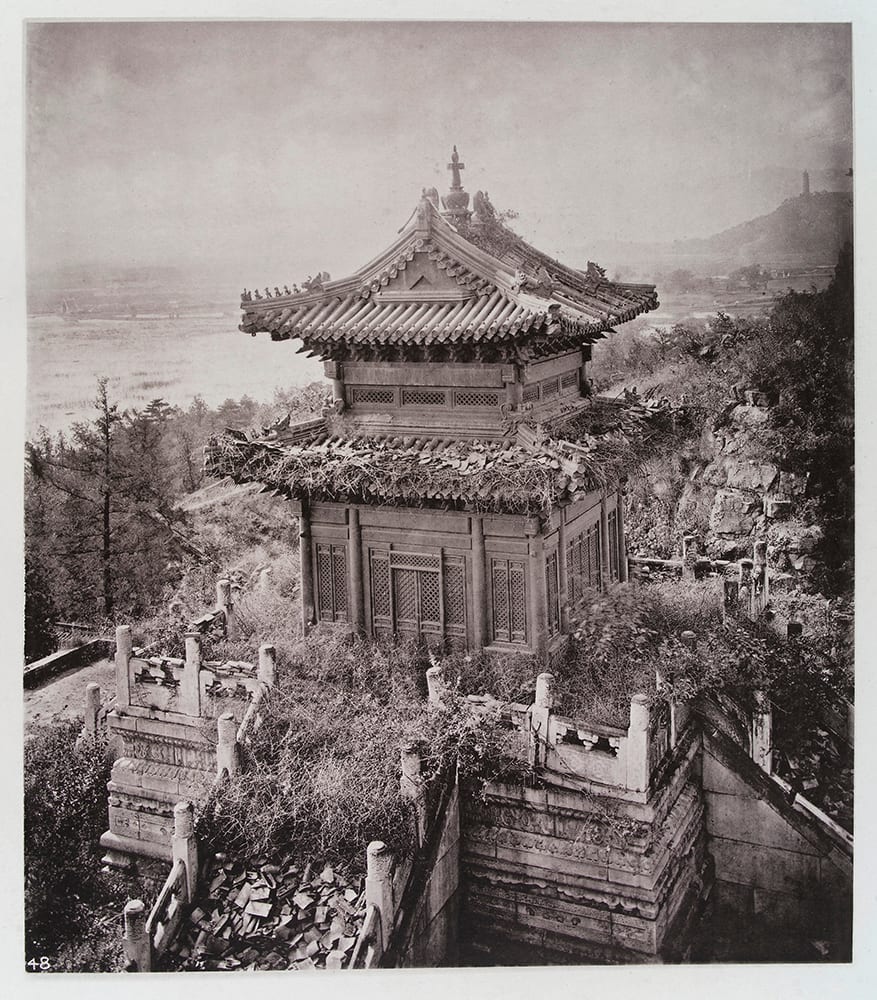

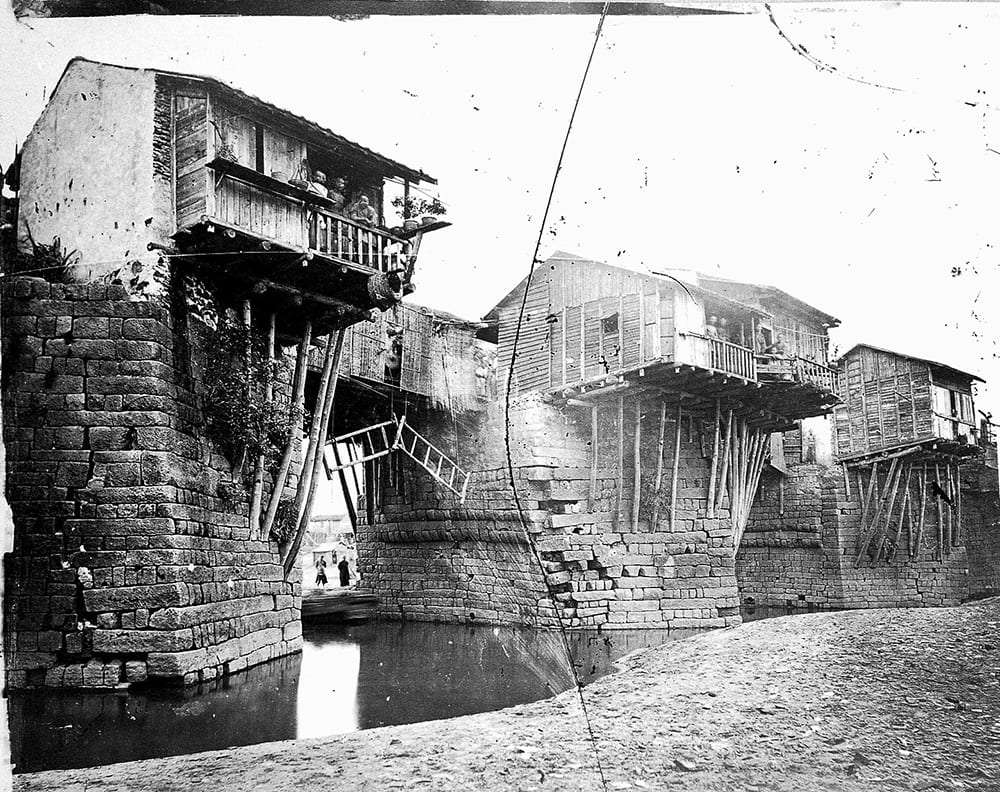

First lavishly published in a series of books titled Illustrations of China and Its People (now available to read free online at the Yale University Library: volume one, volume two, volume three, volume four), they now constitute some of the earliest and richest direct visual records of Chinese landscapes, cityscapes, and society as they were in the late 19th century.

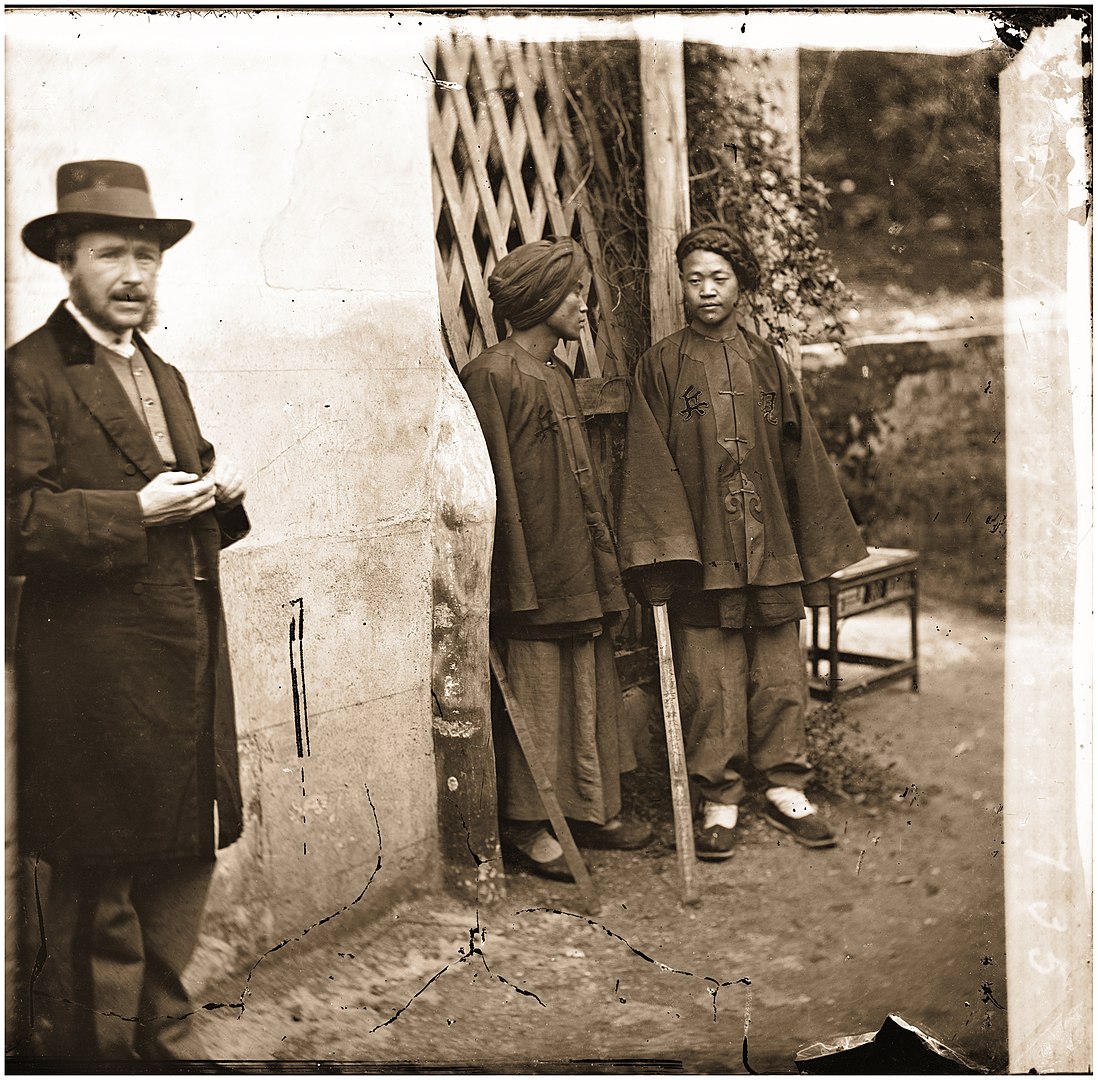

“The first Western photographer to travel widely through the length and breadth of China,” Thomson brought his camera on journeys “far more extensive than those undertaken by most Westerners of his generation,” extending “beyond the relative comfort and safety of the coastal treaty ports.” Those words come from scholar of the 19th-century Allen Hockley, whose five-part visual essay “John Thomson’s China” at MIT Visualizing Cultures provides a detailed overview and historical contextualization of Thomson’s work in Asia.

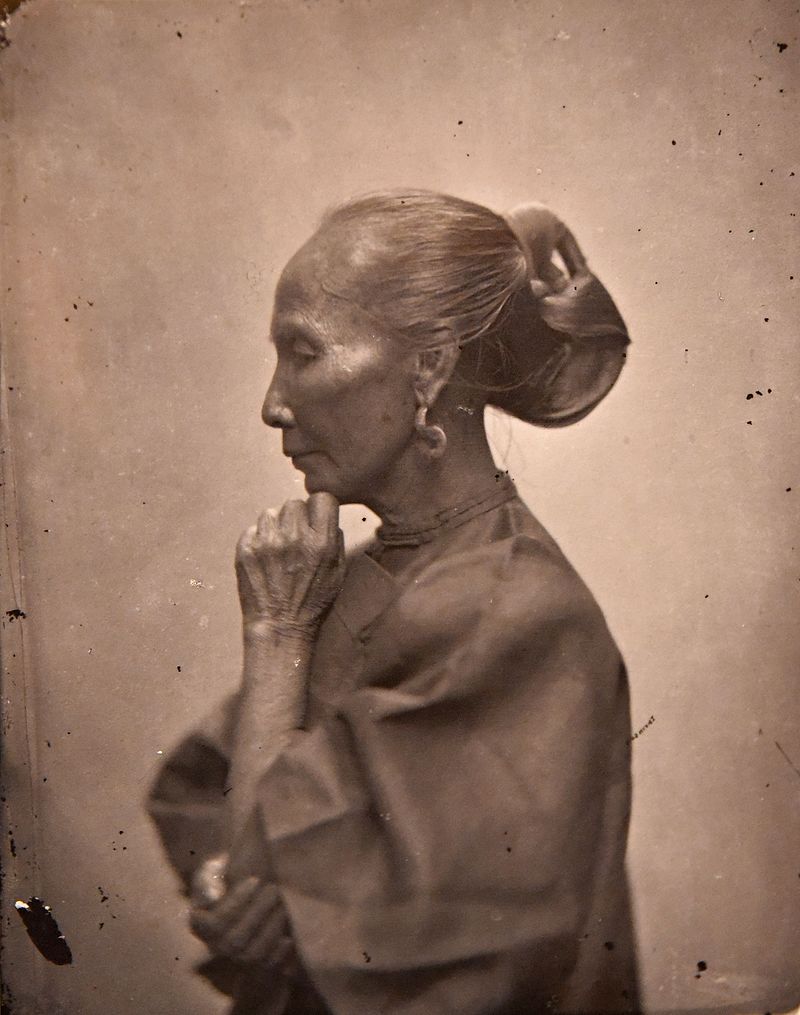

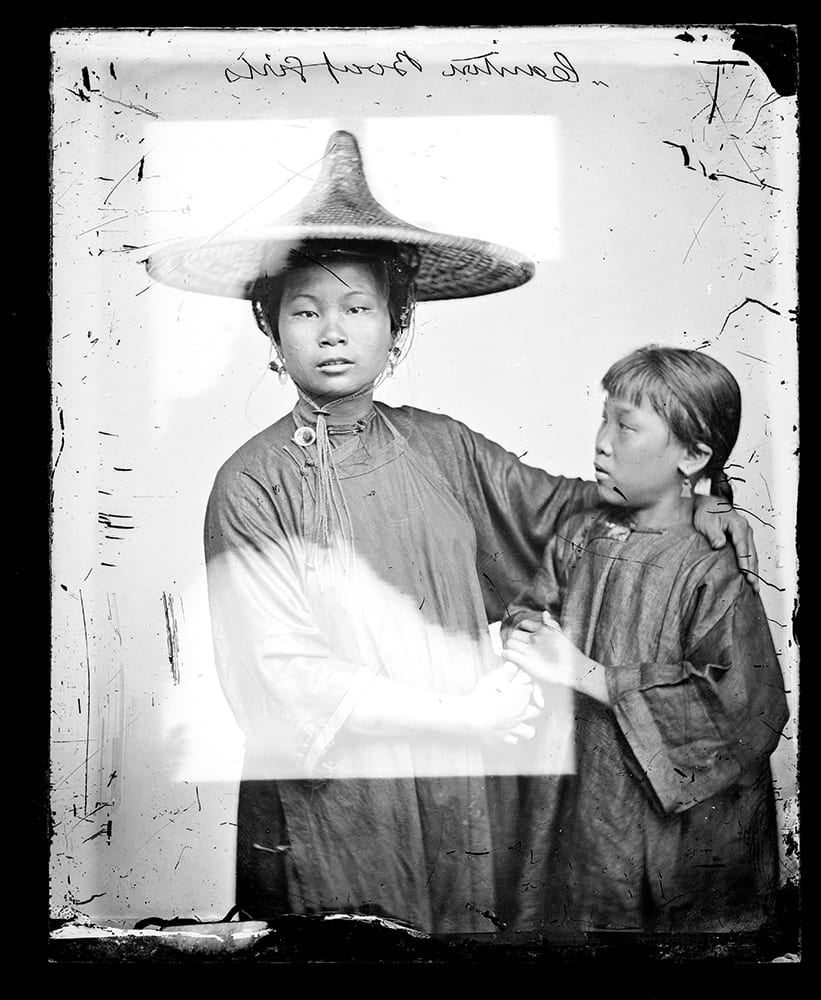

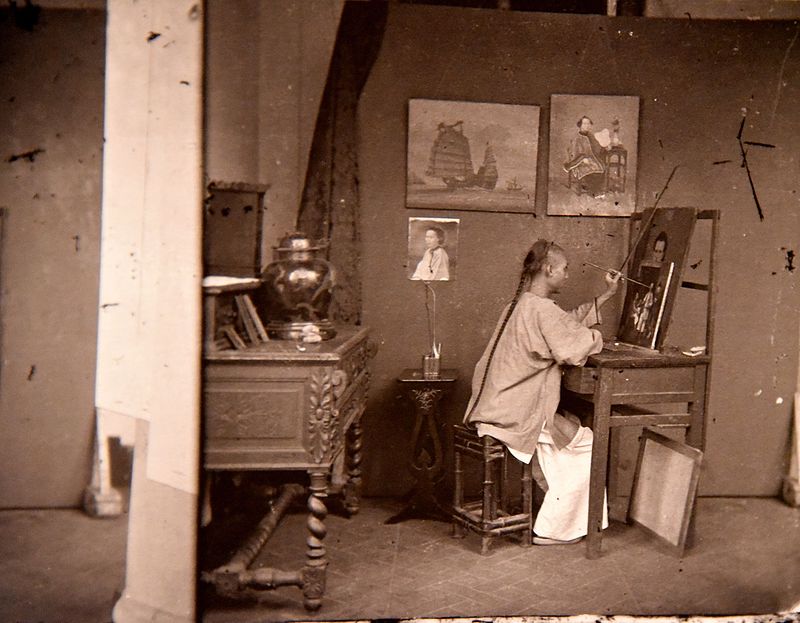

Thomson’s photographs, writes Hockley, “fall into two broad categories: scenic views and types. Views encompassed both natural landscapes and built environments. They could be panoramic, taking in large swaths of scenery, or they might highlight specific natural phenomena or individual structures.”

Types “focused on the manners and customs of Chinese people and tended to highlight the defining features of gender, age, class, ethnicity, and occupation.” A century and a half later, both Thomson’s views and types have given scholars in a variety of disciplines much to discuss.

“It is clear from his commentary to Illustrations of China that, however sympathetic he was towards Chinese people, he could often be superior and high-handed,” writes Andrew Hiller at Visualizing China. “If Thomson never sought to question the validity of Britain’s presence, his attitude towards China was ambivalent. Whilst critical of what he saw as the corruption and obfuscation of Qing officials, he nevertheless could see the country’s potential.”

Thomson also helped others to see that potential — or at least those who could afford to buy his books, whose prices matched the quality of their production. But today, thanks to online archives like Historical Photographs of China and Wellcome Collection, they’re free for everyone to behold. China itself has become much more accessible since Thomson’s day, of course, but it’s famously a much different place than it was 25 years ago, let alone 150 years ago. The land through which he traveled — and of which he took so many of the very earliest photographs — is now infinitely less accessible to us than it ever was to his fellow Westerners of the 19th century.

Hear a lecture on Thomson’s photography in China from the University of London here.

Related Content:

How Vividly Colorized Photos Helped Introduce Japan to the World in the 19th Century

1850s Japan Comes to Life in 3D, Color Photos: See the Stereoscopic Photography of T. Enami

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Behold the Photographs of John Thomson, the First Western Photographer to Travel Widely Through China (1870s) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3AB5wOT

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment