When the Nobel Prize Committee Rejected The Lord of the Rings: Tolkien “Has Not Measured Up to Storytelling of the Highest Quality” (1961)

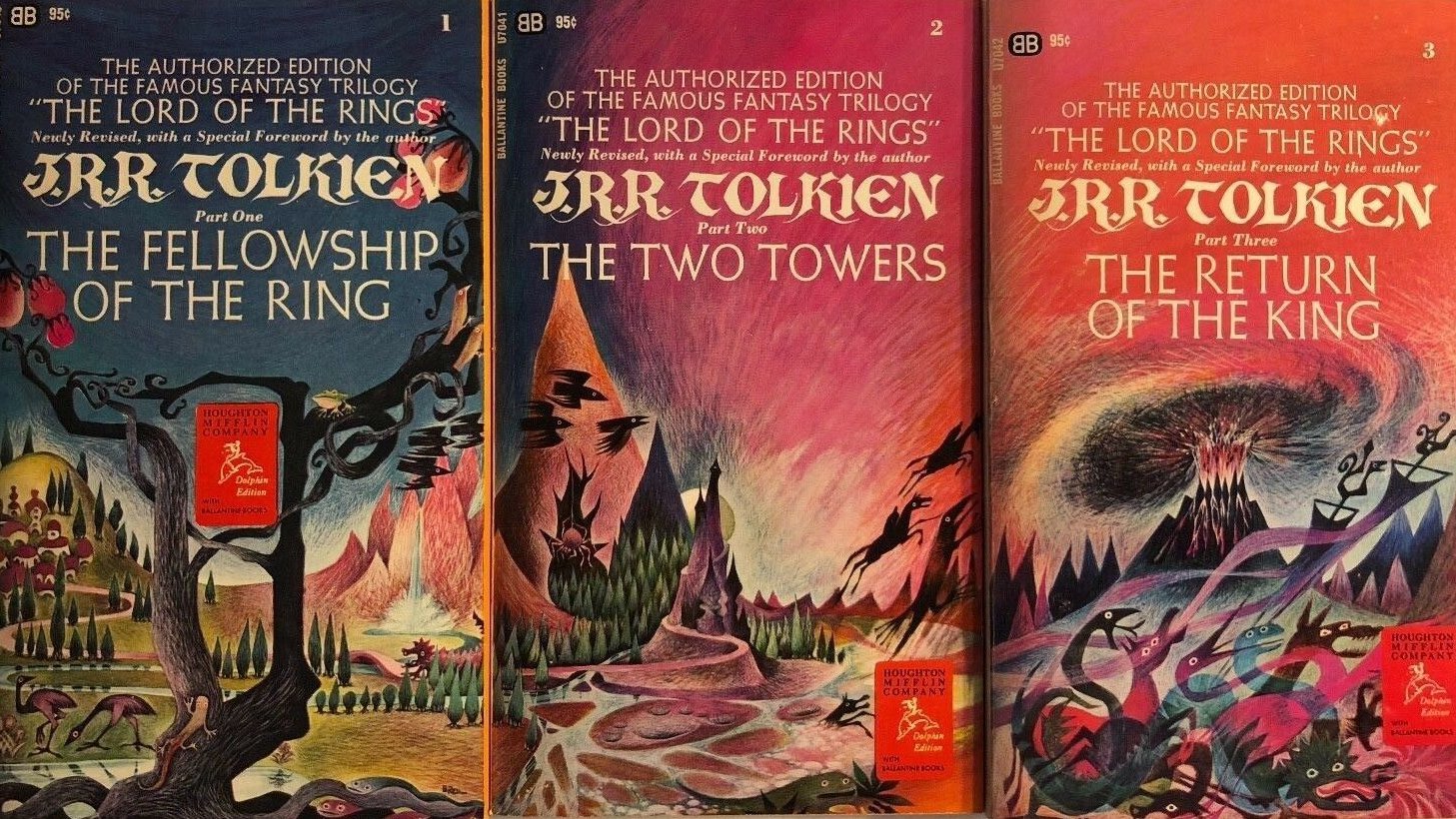

When J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings books appeared in the mid-1950s, they were met with very mixed reviews, an unsurprising reception given that nothing like them had been written for adult readers since Edmund Spencer’s epic 16th century English poem The Faerie Queene, perhaps. At least, this was the contention of reviewer Richard Hughes, who went on to write that “for width of imagination,” The Lord of the Rings “almost beggars parallel.”

Scottish writer Naomi Mitchison did find a comparison: to Sir Thomas Malory, author of the 15th century Le Morte d’Arthur — hardly misplaced, given Tolkien’s day job as an Oxford don of English literature, but not the sort of thing that passed for contemporary writing in the 1950s, notwithstanding the serious appreciation of writers like W.H. Auden for Tolkien’s trilogy. “No previous writer,” the poet remarked in a New York Times review, “has, to my knowledge, created an imaginary world and a feigned history in such detail.”

Auden did find fault with Tolkien’s poetry, a fact upon which critic Edmund Wilson seized in his scathing 1956 Lord of the Rings review. “Mr. Auden is apparently quite insensitive — through lack of interest in the other department,” wrote Wilson, “to the fact that Tolkien’s prose is just as bad. Prose and verse are on the same level of professorial amateurishness.” Five years later, the Nobel prize jury would make the same judgement when they excluded Tolkien’s books from consideration. Tolkien’s prose, wrote jury member Anders Österling, “has not in any way measured up to storytelling of the highest quality.”

The note was discovered recently by Swedish journalist Andreas Ekström, who delved into the Nobel archive for 1961 and found that “the jury passed over names including Lawrence Durrell, Robert Frost, Graham Green, E.M. Forster, and Tolkien to come up with their eventual winner, Yugoslavian writer Ivo Andri?,” as Alison Flood reports at The Guardian. (The Nobel archives are sealed until 50 years after the year the award is given.) Ekström has been reading through the archives “for the past five years or so,” he says, “and this was the first time I have seen Tolkien’s name among the suggested candidates.” His name appeared on the list chiefly through the machinations of his closest friend and chief supporter, C.S. Lewis.

Lewis, “also of Oxford,” Wilson sneered, “is able to top them all” in praise of Tolkien’s books. From the first appearance of his Middle Earth fantasy in The Hobbit, Lewis promised to “do all in my power to secure for Tolkien’s great book the recognition it deserves,” as he wrote in a 1953 letter to British publisher Stanley Unwin. In what might be considered an unethical promotion of his friend’s work today, Lewis responded tirelessly to critics of the trilogy, going so far, after the publication of The Two Towers, to pen an essay on the subject titled “The Dethronement of Power.” Here, Lewis explains the prolix quality of Tolkien’s prose — that which critics called “tedious” — as a narrative necessity: “I do not think he could have done it any other way.”

Tolkien’s biggest fan also urged readers to spend more time with the books and promised that the rewards would be great. In defense of the second work of the trilogy, he concluded, “the book is too original and too opulent for any final judgment on a first reading. But we know at once that it has done things to us. We are not quite the same men. And though we must ration ourselves in our rereadings, I have little doubt that the book will soon take its place among the indispensables.” And so has all of Tolkien’s work, becoming the literary standard by which high fantasy is measured, with or without a Nobel prize.

Related Content:

Discover J.R.R. Tolkien’s Little-Known and Hand-Illustrated Children’s Book, Mr. Bliss

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

When the Nobel Prize Committee Rejected The Lord of the Rings: Tolkien “Has Not Measured Up to Storytelling of the Highest Quality” (1961) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3EGGCR3

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment