Like most renowned abstract painters, Wassily Kandinsky could also paint realistically. Unlike most renowned abstract painters, he only took up art in earnest after studying economics and law at the University of Moscow. He then found early success teaching those subjects, which seem to have proven too worldly for his sensibilities: at age 30 he enrolled in the Munich Academy to continue the study of art that he’d left off while growing up in Odessa. The surviving paintings he produced at the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th, displayed on Wikipedia’s list of his works, include a variety of landscapes, most presenting German and Russian (or today Ukrainian) landscapes undisturbed by a single human figure.

Kandinsky made dramatic change come with 1903’s The Blue Rider (above). The presence of the titular figure made for an obvious difference from so many of the images he’d created over the previous half-decade; a shift in its very perception of reality made for a less obvious one.

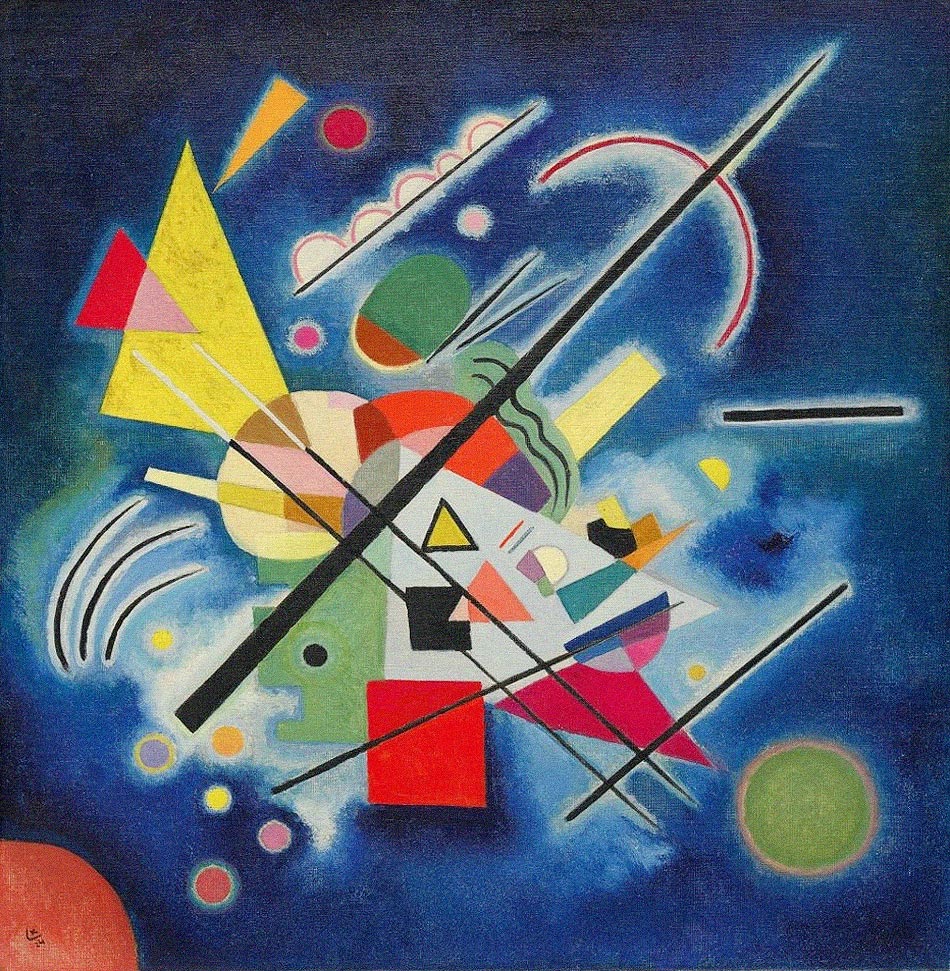

This is not the world as we normally see it, and Kandinsky’s track record of highly representative paintings tells us that he must deliberately have chosen to paint it it that way. With fellow artists like August Macke, Franz Marc, Albert Bloch, and Gabriele Münter, he went on to form the Blue Rider Group, whose publications argued for abstract art’s capability to attain great spiritual heights, especially through color.

“Gradually Kandinsky makes departures from the external ‘world as a model’ into the world of ‘paint as a thing in itself,'” writes painter Markus Ray. “Still depicting ‘worldly scenes,’ these paintings start to take on purer colors and shapes. He reduces volumes into simple shapes, and colors into bright and vibrant hues. One can still make out the scene, but the shapes and colors begin to take on a life of their own.” This is especially true of the scenes Kandinsky painted in Bavaria, such as 1909’s Railway near Murnau above. The outbreak of World War I five years later sent him back to Russia, where he continued his pioneering journey toward a visual art equal in expressive power to music, which he called his “ultimate teacher.” But by the early 1920s it had become clear that his increasingly individualistic and non-representative tendencies wouldn’t sit well with the Soviet cultural powers that be.

A return to Germany was in order. “In 1921, at the age of 55, Kandinsky moved to Weimar to teach mural painting and introductory analytical drawing at the newly founded Bauhaus school,” says Christie’s. “There he worked alongside the likes of Paul Klee, László Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers,” and also expanded on Goethe‘s theories of color. A true believer in the Bauhaus’ “philosophy of social improvement through art,” Kandinsky also wound up among the artists whose work was exhibited in the Nazi Party’s “Degenerate Art Exhibition” of 1937. By that time the Bauhaus was dissolved and Kandinsky had resettled in Paris, where until his death in 1944 (as evidenced by Wikipedia’s list of his paintings) he kept pushing further into abstraction, seeking ever-purer expressions of the human soul until the very end.

Related Content:

Time Travel Back to 1926 and Watch Wassily Kandinsky Make Art in Some Rare Vintage Video

An Interactive Social Network of Abstract Artists: Kandinsky, Picasso, Brancusi & Many More

How to Paint Like Kandinsky, Picasso, Warhol & More: A Video Series from the Tate

The Guggenheim Puts Online 1700 Great Works of Modern Art from 625 Artists

Take a Journey Through 933 Paintings by Salvador Dalí & Watch His Signature Surrealism Emerge

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

The Evolution of Kandinsky’s Painting: A Journey from Realism to Vibrant Abstraction Over 46 Years is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3lA5VMf

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment