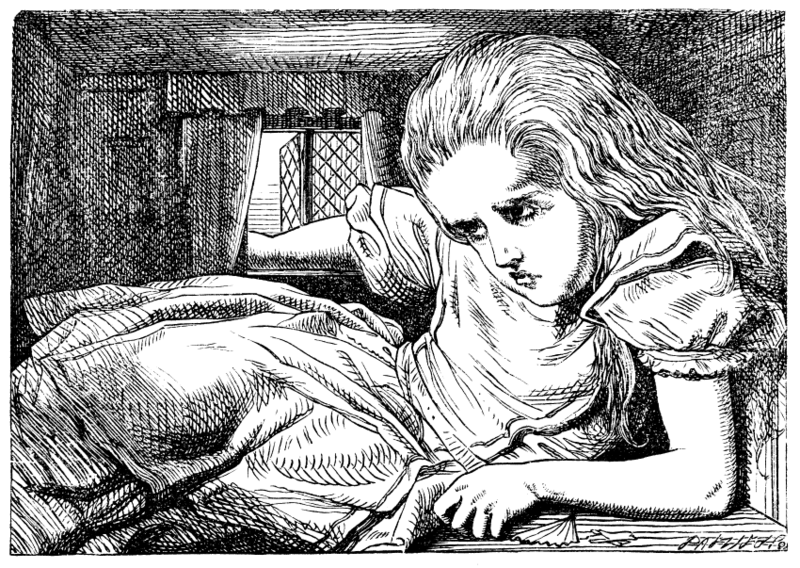

Alice in Wonderland Syndrome: The Real Perceptual Disorder That May Have Shaped Lewis Carroll’s Creative World

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland isn’t just a beloved children’s story: it’s also a neuropsychological syndrome. Or rather the words “Alice in Wonderland,” as Lewis Carroll’s book is commonly known, have also become attached to a condition that, though not harmful in itself, causes distortions in the sufferer’s perception of reality. Other names include dysmetropsia or Todd’s syndrome, the latter of which pays tribute to the consultant psychiatrist John Todd, who defined the disorder in 1955. He described his patients as seeing some objects as much larger than they really were and other objects as much smaller, resulting in challenges not entirely unlike those faced by Alice when put by Carroll through her growing-and-shrinking paces.

Todd also suggested that Carroll had written from experience, drawing inspiration from the hallucinations he experienced when afflicted with what he called “bilious headache.” The transformations Alice feels herself undergoing after she drinks from the “DRINK ME” bottle and eats the “EAT ME” cake are now known, in the neuropsychological literature, as macropsia and micropsia.

“I was in the kitchen talking to my wife,” writes novelist Craig Russell of one of his own bouts of the latter. “I was hugely animated and full of energy, having just put three days’ worth of writing on the page in one morning and was bursting with ideas for new books. Then, quite calmly, I explained to my wife that half her face had disappeared. As I looked around me, bits of the world were missing too.”

Though “many have speculated that Lewis Carroll took some kind of mind-altering drug and based the Alice books on his hallucinatory experiences,” writes Russell, “the truth is that he too suffered from the condition, but in a more severe and protracted way,” combined with ocular migraine. Russell also notes that the sci-fi visionary Philip K. Dick, though “never diagnosed as suffering from migrainous aura or temporal lobe epilepsy,” left behind a body of work that has has given rise to “a growing belief that the experiences he described were attributable to the latter, particularly.” Suitably, classic Alice in Wonderland syndrome “tends to be much more common in childhood” and disappear in maturity. One sufferer documented in the scientific literature is just six years old, younger even than Carroll’s eternal little girl — presumably, an eternal seer of reality in her own way.

Related Content:

A Beautiful 1870 Visualization of the Hallucinations That Come Before a Migraine

Lewis Carroll’s Photographs of Alice Liddell, the Inspiration for Alice in Wonderland

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Illustrated by Salvador Dalí in 1969, Finally Gets Reissued

Curious Alice — The 1971 Anti-Drug Movie Based on Alice in Wonderland That Made Drugs Look Like Fun

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Alice in Wonderland Syndrome: The Real Perceptual Disorder That May Have Shaped Lewis Carroll’s Creative World is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2Xthi0h

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment