Elvis Presley Gets the Polio Vaccine on The Ed Sullivan Show, Persuading Millions to Get Vaccinated (1956)

No one living has experienced a viral event the size and scope of COVID-19. Maybe the unprecedented nature of the pandemic explains some of the vaccine resistance. Diseases of such virulence became rare in places with ready access to vaccines, and thus, ironically, over time, have come to seem less dangerous. But there are still many people in wealthy nations who remember polio, an epidemic that dragged on through the first half of the 20th century before Jonas Salk perfected his vaccine in the mid-fifties.

Polio’s devastation has been summed up visually in textbooks and documentaries by the terrifying iron lung, an early ventilator. “At the height of the outbreaks in the late 1940s,” Meilan Solly writes at Smithsonian, “polio paralyzed an average of more than 35,000 people each year,” particularly affecting children, with 3,000 deaths in 1952 alone. “Spread virally, it proved fatal for two out of ten victims afflicted with paralysis. Though millions of parents rushed to inoculate their children following the introduction of Jonas Salk’s vaccine in 1955, teenagers and young adults had proven more reluctant to get the shot.”

At the time, there were no violent, organized protests against the vaccine, nor was resistance framed as a patriotic act of political loyalty. But “cost, apathy and ignorance became serious setbacks to the eradication effort,” says historian Stephen Mawdsley. And, then as now, irresponsible media personalities with large platforms and little knowledge could do a lot of harm to the public’s confidence in life-saving public health measures, as when influential gossip columnist Walter Winchell wrote that the vaccine “may be a killer,” discouraging countless readers from getting a shot.

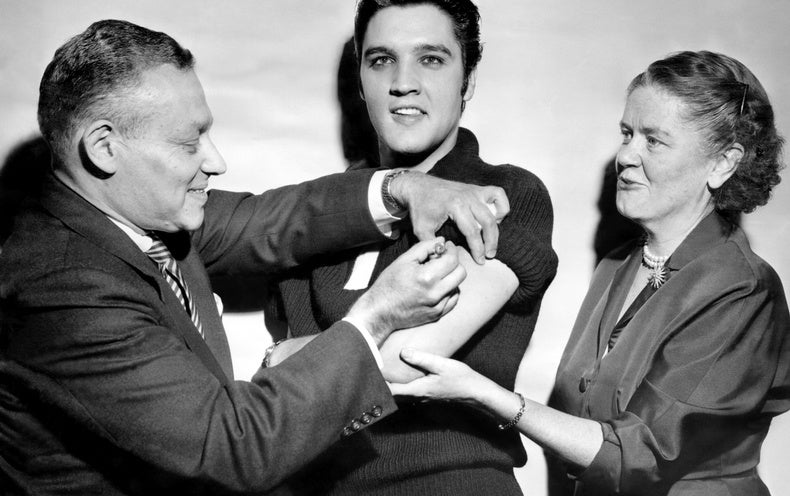

When Elvis Presley made his first appearance on Ed Sullivan’s show in 1956, “immunization levels among American teens were at an abysmal 0.6 percent,” note Hal Hershfield and Ilana Brody at Scientific American. To counter impressions that the polio vaccine was dangerous, public health officials did not solely rely on getting more and better information to the public; they also took seriously what Hershfield and Brody call the “crucial ingredients inherent to many of the most effective behavioral change campaigns: social influence, social norms and vivid examples.” Satisfying all three, Elvis stepped up and agreed to get vaccinated “in front of millions” backstage before his second appearance on the Sullivan show.

Elvis could not have been more famous, and the campaign was a success for its target audience, establishing a new social norm through influence and example: “Vaccination rates among American youth skyrocketed to 80 percent after just six months.” Despite the threat he supposedly posed to the establishment, Elvis himself was ready to serve the public. “I certainly never wanna do anything,” he said, “that would be a wrong influence.” See in the short video at the top how American public health officials stopped millions of preventable deaths and disabilities by admitting a fact propagandists and advertisers never shy from — humans, on the whole, are easily persuaded by celebrities. Sometimes they can even be persuaded for the good.

Related Content:

Yo-Yo Ma Plays an Impromptu Performance in Vaccine Clinic After Receiving 2nd Dose

Dying in the Name of Vaccine Freedom

How Do Vaccines (Including the COVID-19 Vaccines) Work?: Watch Animated Introductions

How Vaccines Improved Our World In One Graphic

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Elvis Presley Gets the Polio Vaccine on The Ed Sullivan Show, Persuading Millions to Get Vaccinated (1956) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3tPADo7

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment