“For a normal person back in the day,” says LEGO designer/architect Rok Kobe about the Colosseum in Rome, “You had never seen a building that was over a story high. And to be confronted with such an amazing piece of engineering that’s almost 200-meters wide and 50 meters tall, it was unprecedented.”

Similarly, any LEGO fan might feel this awe while greeting this month’s debut of the LEGO Colosseum. At 9036 pieces it has broken the record as the biggest LEGO set in existence, beating out the Star Wars’ Millennium Falcon (7,541 pieces) and the Taj Mahal (5,923 pieces). Every few years LEGO steps up its game, which might possibly end with a neighborhood-devouring replica of the Great Wall of China. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

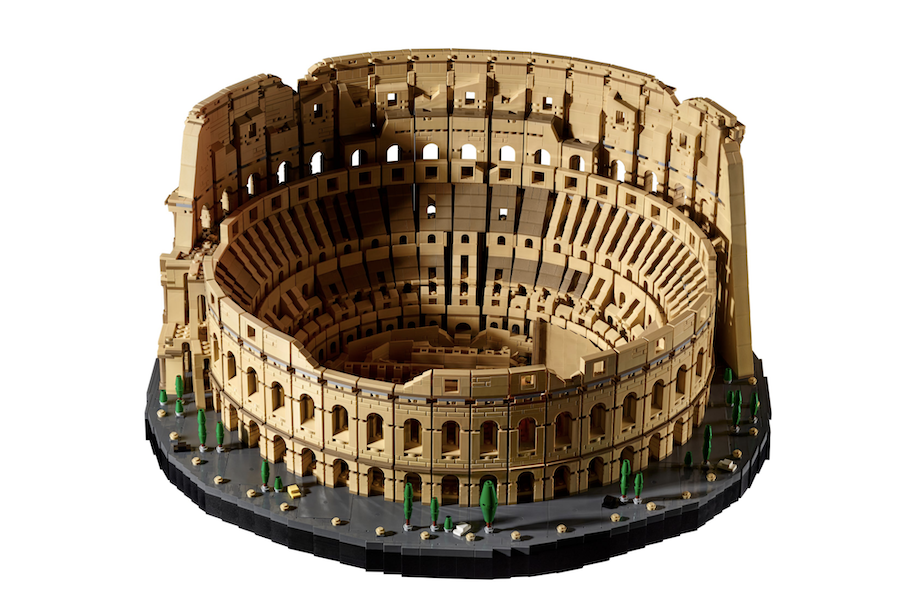

The Colosseum’s facade has been faithfully recreated on all three levels, with the Doric columns at the bottom, the Ionic columns in the middle, and the Corinthian columns on top. And it also adds the contemporary part of the arena that has been rebuilt to show the original level of the arena in Roman times.

The original Colosseum was built over eight years between year 72 AD and 80 AD and between two emperors, Vespasian and Titus. And though we know it as a sandstone-colored structure these days, archeologists have determined it was also colored red, black, and azure. The LEGO version may not be so dramatic, but it does contain a bit more color than the real-life model.

Rok Kobe knows of what he speaks and models. Growing up in Ljubljana, capitol of Slovenia, he would play on the Roman ruins in the city center, especially the Roman Wall. “The five year old would be proud of the adult that got to design this LEGO set,” he says.

At $549.99, this is not a frivolous purchase. But it will bring an adult hours of fun and keep them occupied.

Related Content:

The Frank Lloyd Wright Lego Set

Cambridge University to Create a Lego Professorship

The LEGO Turing Machine Gives a Quick Primer on How Your Computer Works

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the Notes from the Shed podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, and/or watch his films here.

With 9,036 Pieces, the Roman Colosseum Is the Largest Lego Set Ever is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/36bdFgT

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment