A Quay Brothers Animation Explains Anamorphosis, the Renaissance Illusion That Hides Pictures within Pictures

First appearances can be deceiving.

Take physicist Emmanuel Maignan’s 1642 fresco in a corridor of Rome’s Trinità dei Monti monastery.

Viewed head on, it appears to be a somewhat unconventional landscape in which one of the few remaining branches of a mutilated tree spreads over a city, far in the distance. Streaky clouds suggest heavy weather is brewing.

Stroll to the end of the corridor and take another look. You’ll find that the tree has contracted, and the clouds have reconfigured themselves into a portrait of Saint Francesco of Paola, praying beneath its boughs.

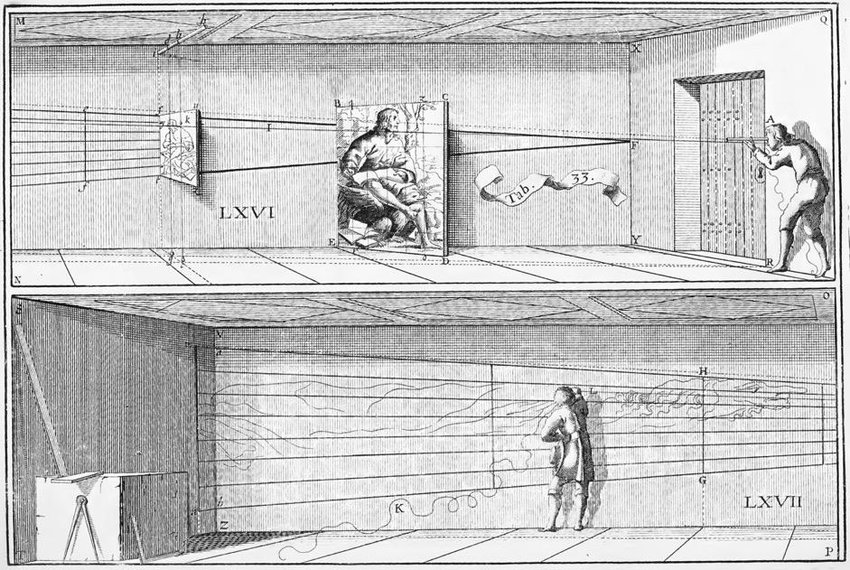

It’s a prime example of oblique anamorphosis, an image that has been deliberately distorted by an artist well versed in perspective, with the end result that the image’s true nature will only be revealed to those viewing the work from an unconventional point.

The Quay Brothers‘ documentary short, above, a collaboration with art historian Roger Cardinal, uses a combination of their delightfully creepy signature puppet stop motion, as well as animated 3-D cut outs, to lift the curtains on how the human eye can be manipulated, using principles of perspective.

Anamorphosis may not seem like such a feat in an age when a number of software programs can provide a major assist, but why would Renaissance artists put themselves to so much extra trouble?

The Quay Brothers delve into this too.

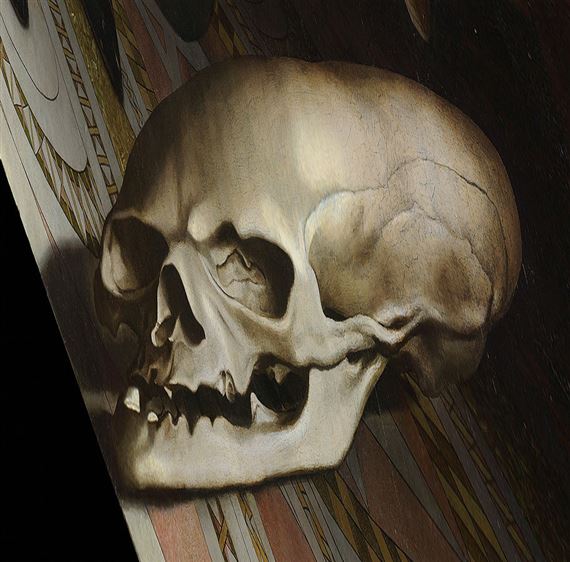

Perhaps the artist was injecting a bit of social criticism, like Hans Holbein the Younger, whose 1533 portrait, The Ambassadors, includes a secret anamorphic skull. This could be taken as a jab at the excesses of the wealthy young diplomats who provide the painting’s subject, except that the one who commissioned the work, Jean de Dinteville, prized the motto “Memento mori.”

Maybe he knowingly ordered up the naked death’s head to go along with his ermine and bling, an example of having one’s cake and eating it too, and yet another dizzying head trip for those viewing the painting from the intended angle.

(Betcha didn’t have to work too hard to guess the skull’s location, though…)

Or an artist might choose to employ anamorphosis as a brown paper wrapper of sorts, as in the case of Erhard Schön‘s erotic woodblock prints.

Elsewhere, the goal was to emphasize patience, reflection, and cleaving to a pious path by rewarding those who craned their necks toward a spiritual peephole with an appropriately religious view.

(Pity the poor pilgrim who stepped up expecting Erhard Schön…)

For a 21st-century take on anamorphic art, have a look at the work of the graffiti collective TRULY | Urban Artists here.

The Quay Brothers’ short film, “De Artificiali Perspectiva, or Anamorphosis,” has been made available on The Met Museum’s YouTube channel.

via Aeon

Related Content:

Optical Poems by Oskar Fischinger, the Avant-Garde Animator Despised by Hitler, Dissed by Disney

The Anatomical Drawings of Renaissance Man, Leonardo da Vinci

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

A Quay Brothers Animation Explains Anamorphosis, the Renaissance Illusion That Hides Pictures within Pictures is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3oS1KMg

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment