The Beatles Create an Abstract Collaborative Painting, Images of a Woman, During Three Days of Lockdown in Japan (1966)

One of the earliest known non-human visual artists, Congo the chimpanzee, learned to draw in 1956 at the age of two. Moody, fiercely protective of his work, and particular about his process, he made around 400 drawings and paintings in a style described as “lyrical abstract impressionism.” He appeared several times on British television before his death in 1964. He counted Picasso among his fans and, in a 2005 auction, outsold Warhol and Renoir.

One wonders if whoever gave the four-headed beast known as the Beatles canvas and paint (“possibly Brian Epstein or their Japanese promoter, Tats Nagashima”) remembered Congo as the fab four bounced off the walls in their hotel rooms in Tokyo during their last, 1966 tour, when extra security forced them to stay inside for three full days. Or perhaps their keepers were inspired by the humane practice of art therapy, coming into its own at the same time in mental health circles with the founding of the British Association of Art Therapists in 1964.

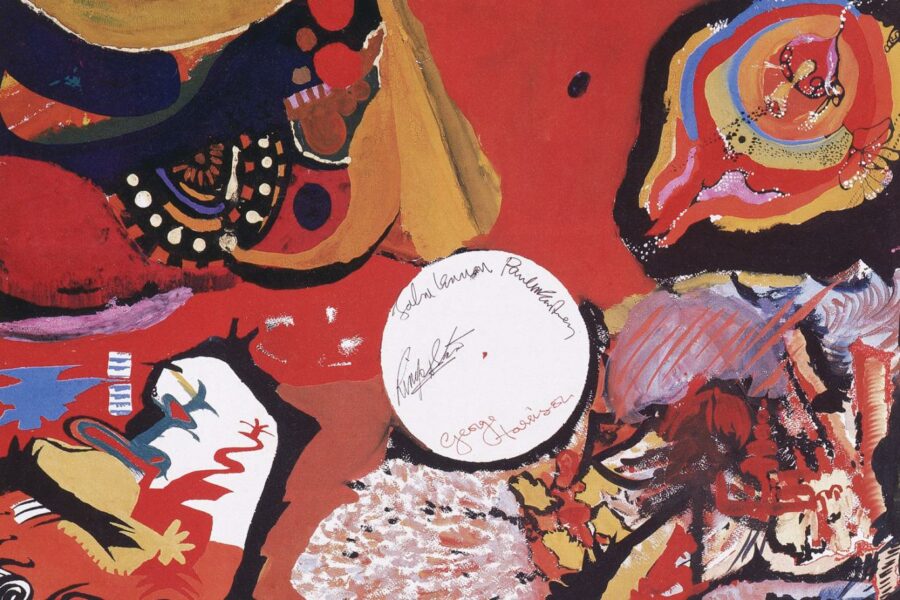

“According to photographer Robert Whitaker,” David Wolman writes at The Atlantic, the Beatles’ manager “brought the guys a bunch of art supplies to help pass the time. Then Epstein set a large canvas on a table and placed a lamp in the middle. Each member of the group set to work painting a corner—comic strippy for Ringo, psychedelic for John.” Paul’s corner resembles an oddly erotic sea creature, George’s the spiritual abstractions of Kandinsky. According to the Beatles Bible, it was Nagashima “who suggested that the completed painting be auctioned for charity.”

Whitaker documented the experiment and later pronounced it an immediate success: “I never saw them calmer, more contented than at this time… They’d stop, go and do a concert, and then it was ‘Let’s go back to the picture!’” Once finished, the lamp was lifted, all four signed their names in the center, and the painting was titled Images of A Woman, which may be no indication of the artists’ intentions. But who knows what bawdy scouser humor passed between them as they worked.

The painting then passed to cinema executive Tetsusaburo Shimoyama, whose widow auctioned it in 1989 to wealthy record store owner Takao Nishino, who had seen them at Budokan in 1966 during the same historic tour that produced the painting. Then it ended up under a bed for twenty years before being auctioned again in 2012. It’s certainly true the band, most especially Paul and John, had always taken to visual art, as artists themselves or as collectors and appreciators. But this is something special. It represents their only collaborative artwork, aside from some doodles on a card sent to the Monterrey organizers.

When looking at Whitaker’s photographs of the band at work (see video montage above), one doesn’t, of course, think of Congo the chimp or the patients of a psychiatric hospital. Instead, they look like students in a ‘60s alternative school, set loose to create without interruption (but for the occasional mega-concert) to their hearts’ content. Maybe Epstein or Nagashima had just seen the 1966 National Film Board of Canada documentary Summerhill, about just such a school in England? Whatever inspired the zeitgeist-y moment, we can see why it never came again. That year, they played their final concert and retired to the studio, where they could lock themselves away with their preferred means of creative distraction.

Related Content:

When the Beatles Refused to Play Before Segregated Audiences on Their First U.S. Tour (1964)

Meet Congo the Chimp, London’s Sensational 1950s Abstract Painter

How “Strawberry Fields Forever” Contains “the Craziest Edit” in Beatles History

Audio: The Beatles Play Their Final Concert at Candlestick Park, 1966

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The Beatles Create an Abstract Collaborative Painting, Images of a Woman, During Three Days of Lockdown in Japan (1966) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/37e8kVH

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment