Much of the world has only recently discovered the Moomins, those lovable hippopotamus-like figures — given, it must be said, to moments of startling brusqueness and complexity — created in the 1940s by Finnish artist Tove Jansson. In forms ranging from dolls and school supplies to neck pillows and cellphone cases, they’ve lately become a full-blown craze in South Korea, where I live. Like any massively successful (and highly merchandisable) characters, the Moomins overshadow the rest of Jansson’s oeuvre. Hence exhibitions like Tove Jansson (1914-2001) at London’s Dulwich Picture Gallery, which “aims to rectify the fact that less attention has generally been paid to her range as a visual artist.”

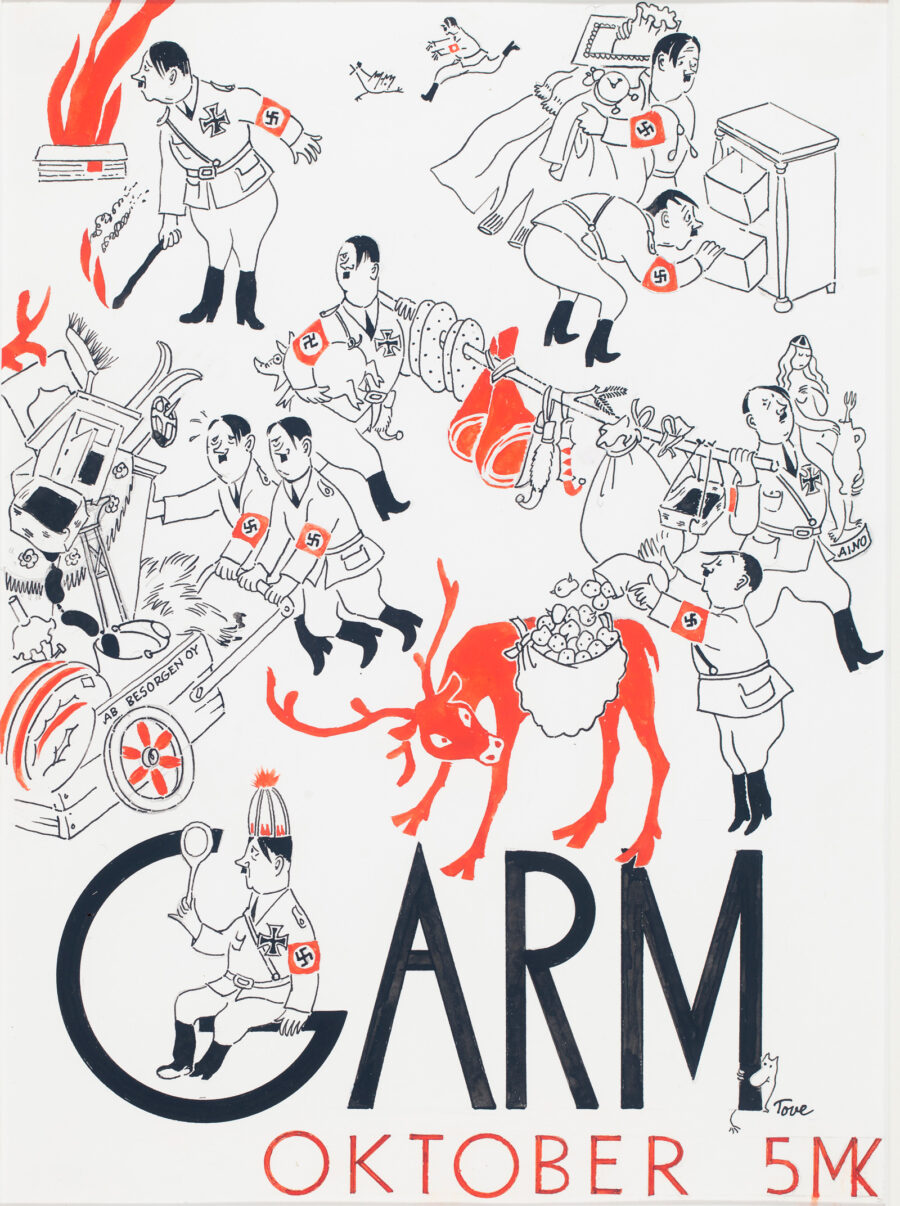

That description comes from Simon Willis’ review of the show in the New York Review of Books. “In October 1944, Tove Jansson drew a cover for Garm, a Finnish satirical magazine, showing a brigade of Adolf Hitlers as pudgy little thieves,” Willis writes. These drawer-rifling, house-burning caricatures “were not unusual for Jansson, who had been belittling Stalin and Hitler in the magazine since the early days of World War II.” But “peeking out at the chaos from behind the magazine’s title,” there was also a “tiny pale figure with a long nose”: a proto-Moomin making an appearance the year before the publication of the first Moomin book. (And even he was forged in mockery, having first been drawn by Jansson, so the story goes, as a caricature of Immanuel Kant.)

Having started contributing to Garm, according to the official Moomin web site, “in 1929 at the young age of 15 (her mother Signe Hammarsten-Jansson had worked for the publication since it started),” she kept on doing so until the magazine folded in 1953.

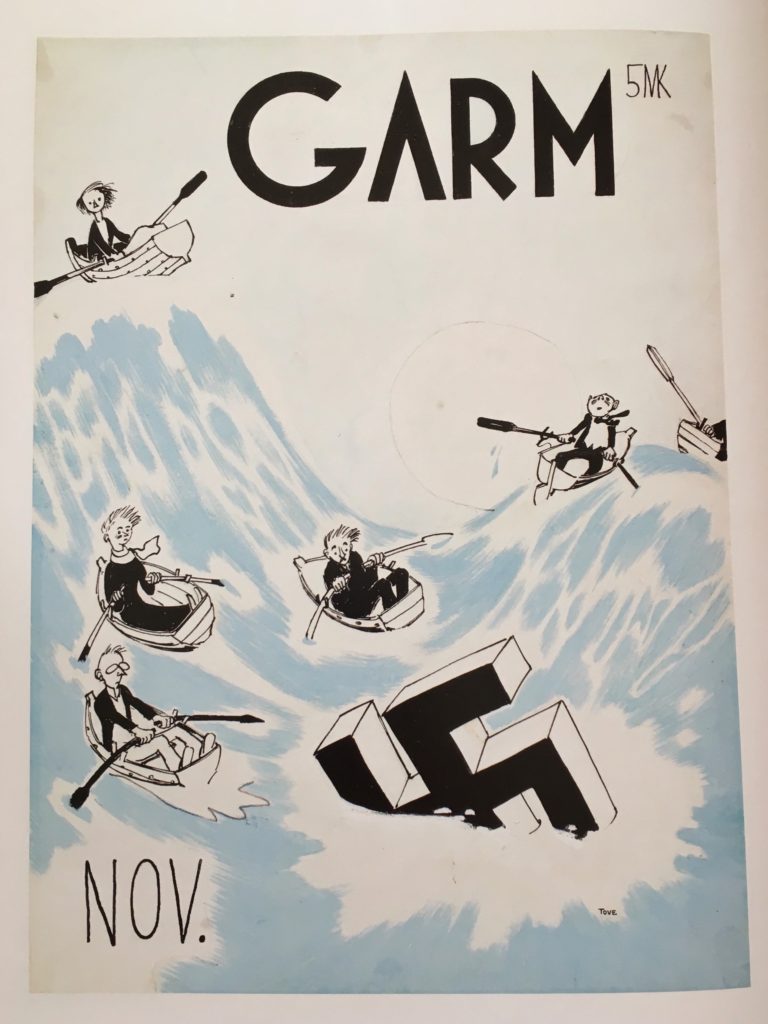

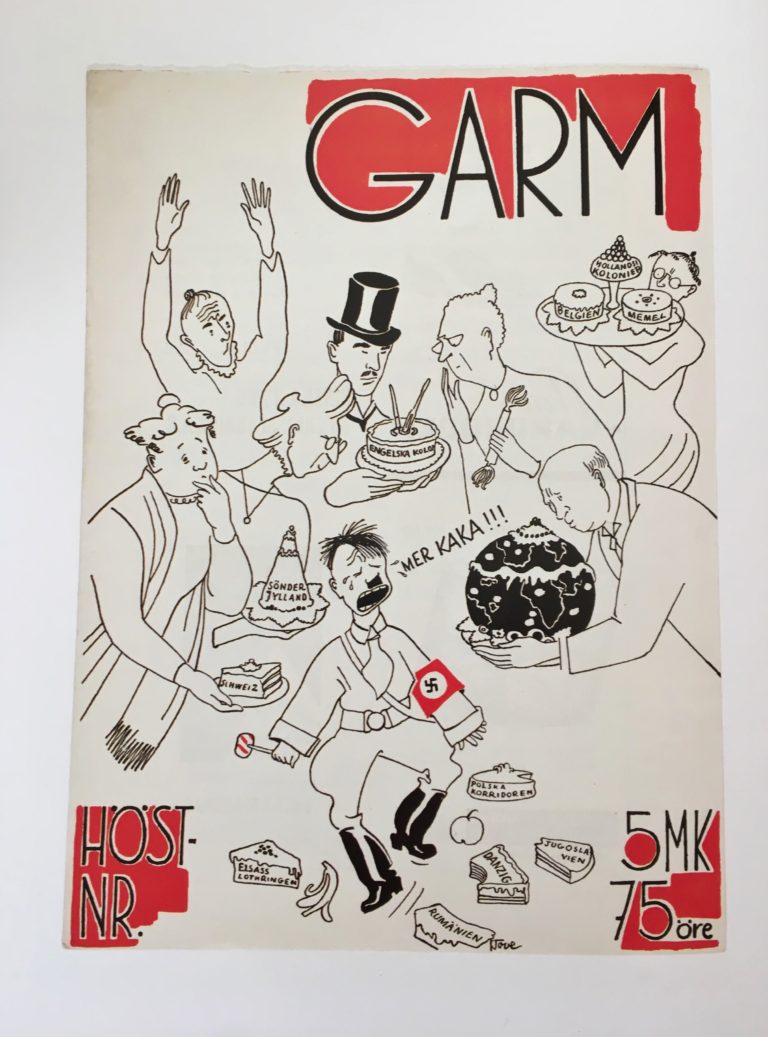

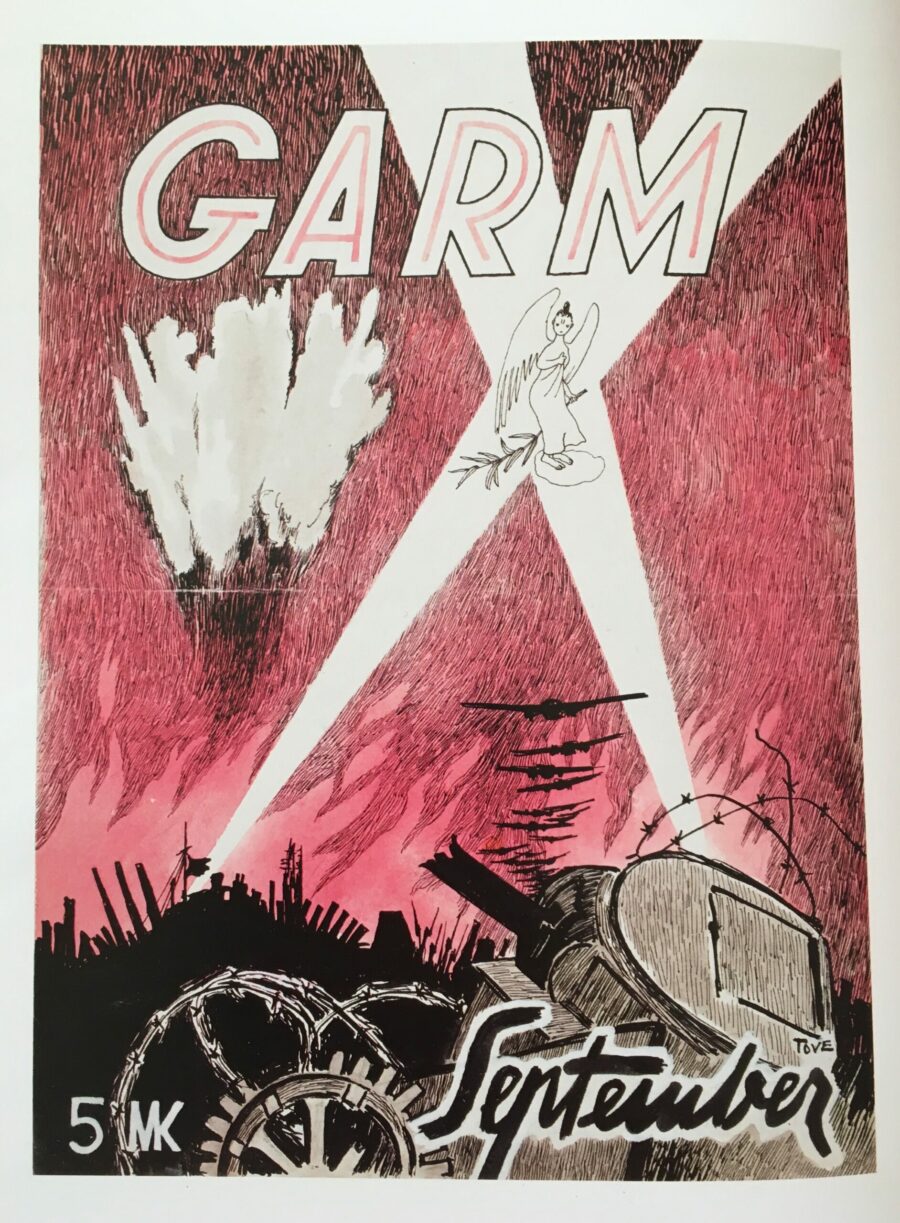

“During that period she drew more than 500 caricatures, a hundred cover images and countless other illustrations for the magazine.” In them, writes Glasstire’s Caleb Mathern, “angels appear on battlefields. Reindeer prepare to rain TNT. An effete, undersized Hitler cries instead of eating slices of cake. Jansson even impugns Stalin’s manhood with an oversized scabbard/undersized sword joke.” To the young Jansson, the best part was the chance, as she later put it, “to be beastly to Stalin and Hitler.”

Even after the success of the Moomins, Jansson continued to draw on the imagery and emotions of war: “The first time we meet young Moomintroll and his Moominmamma in The Moomins and the Great Flood (1945), they are refugees, crossing a strange and threatening landscape in search of shelter. Moominpappa, meanwhile, is absent, as fathers often were during the war,” writes Aeon’s Richard W. Orange. In the next book “the world is threatened by a comet that sucks the water out of the sea, leaving an apocalyptic landscape in its wake.” With the Cold War heating up, the allegory would hardly have gone unnoticed. Like all master satirists, Jansson went on to transcend the solely topical — and indeed, so the increasingly Moomin-crazed world has demonstrated, the boundaries of time and culture.

Related Content:

Donald Duck & Friends Star in World War II Propaganda Cartoons

“The Ducktators”: Loony Tunes Turns Animation into Wartime Propaganda (1942)

Dr. Seuss Draws Anti-Japanese Cartoons During WWII, Then Atones with Horton Hears a Who!

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Before Creating the Moomins, Tove Jansson Drew Satirical Art Mocking Hitler & Stalin is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/34LRKfK

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment