Ray Bradbury Wrote the First Draft of Fahrenheit 451 on Coin-Operated Typewriters, for a Total of $9.80

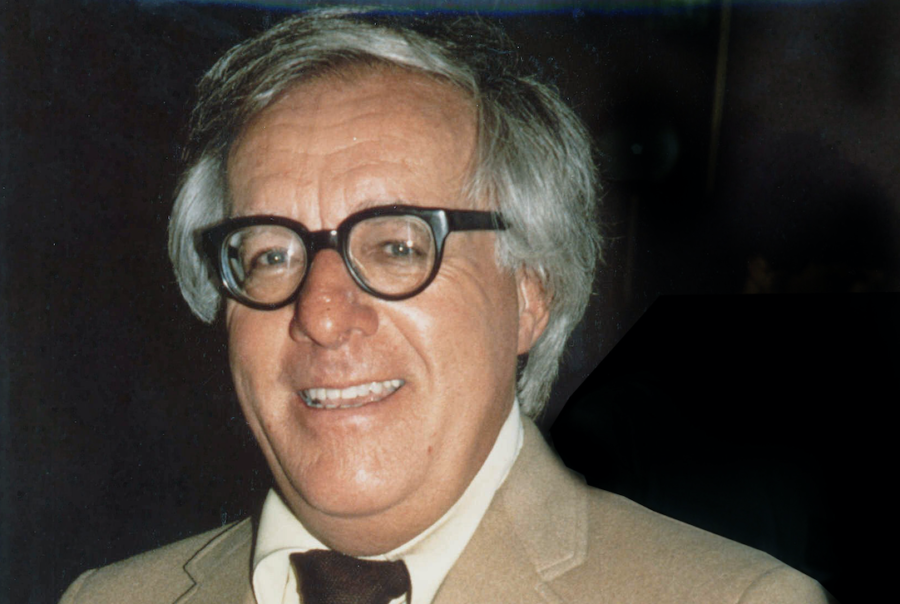

Image by Alan Light, via Wikimedia Commons

It sounds like a third grade math problem: “If Ray Bradbury wrote the first draft of Fahrenheit 451 (1953) on a coin-operated typewriter that charged 10 cents for every 30 minutes, and he spent a total of $9.80, how many hours did it take Ray to write his story?” (If you’re doing the math, that’s great, but you might be in the wrong class.)

Bradbury’s composition of Fahrenheit 451 demonstrates two of the prolific writer’s most insistent demands among his many practical nuggets of writing advice: 1. Always write, all the time; a short story a week, as he told a writer’s symposium in 2001. And, as he told the same group, 2. “Live in the library! Live in the library, for Christ’s sake. Don’t live on your goddamn computer and the internet and all that crap.”

Granted, the library—and the school, and the office, and all the rest of it—now lives in the “goddamn computer” for many of us. But Bradbury’s elaboration of why he ended up in the library in the early 1950s, specifically the basement of UCLA’s Powell Library, will be relatable to any working parent. As he wrote in 1982, he found himself “twice driven; by children to leave at home, and by a typewriter timing device…. Time was indeed money.”

This was a different time, so you’ll need to adjust the currency for 21st century inflation. Also, Bradbury had the 50s’ writer-husband’s prerogative to beg off the childcare. As he explains:

In all the years from 1941 to that time, I had done most of my typing in the family garages… behind the tract house where my wife, Marguerite, and I raised our family. I was driven out of the garage by my loving children, who insisted on coming around to the window and singing and tapping on the panes.

Devoted father Bradbury “had to choose between finishing a story or playing with the girls. I chose to play, of course, which endangered the family income. An office had to be found. We couldn’t afford one.” Bradbury did not write all of Fahrenheit 451 in the library basement. “He ended up with the novella version,” notes UCLA Magazine, “originally called The Fireman and did not come back to it until a publishing company asked if he could add more to the story.”

The speed at which Bradbury wrote, both to save money and to get home to his children, did not cause him to get careless. He looked back on the book 22 years later with pride. “I have changed not one thought or word,” wrote Bradbury in his introduction. He didn’t notice until later that he had named main characters after a paper company, Montag, and pencil company, Faber.

Bradbury told the magazine in 2002, “It was a passionate and exciting time for me. Imagine what it was like to be writing a book about book burning and doing it in a library where the passions of all those authors, living and dead, surrounded me.” When it came to finding the book’s title, however, supposedly the temperature at which books burn, not only did the library fail him, but so too did the university’s chemistry department. To learn the answer, and finish the book, Bradbury finally had to call the fire department.

Related Content:

An Animated Ray Bradbury Explains Why It Takes Being a “Dedicated Madman” to Be a Writer

Ray Bradbury Gives 12 Pieces of Writing Advice to Young Authors (2001)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness.

Ray Bradbury Wrote the First Draft of Fahrenheit 451 on Coin-Operated Typewriters, for a Total of $9.80 is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/35ECbXu

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment