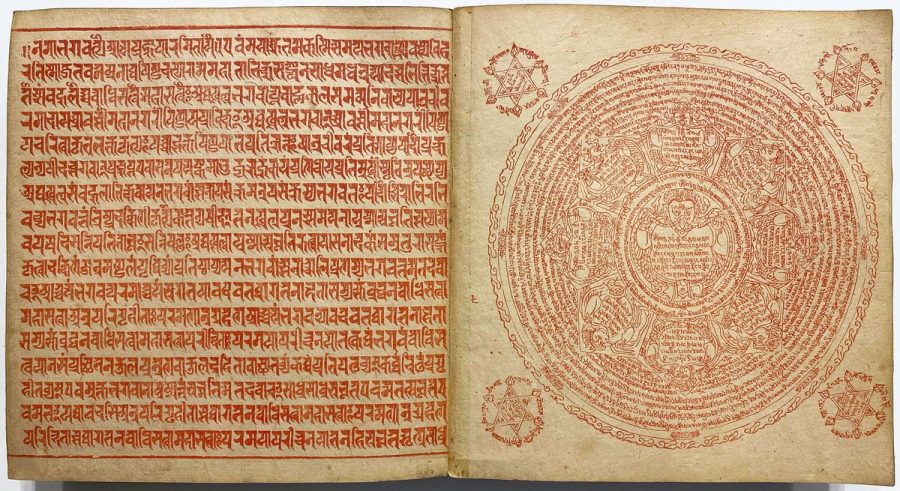

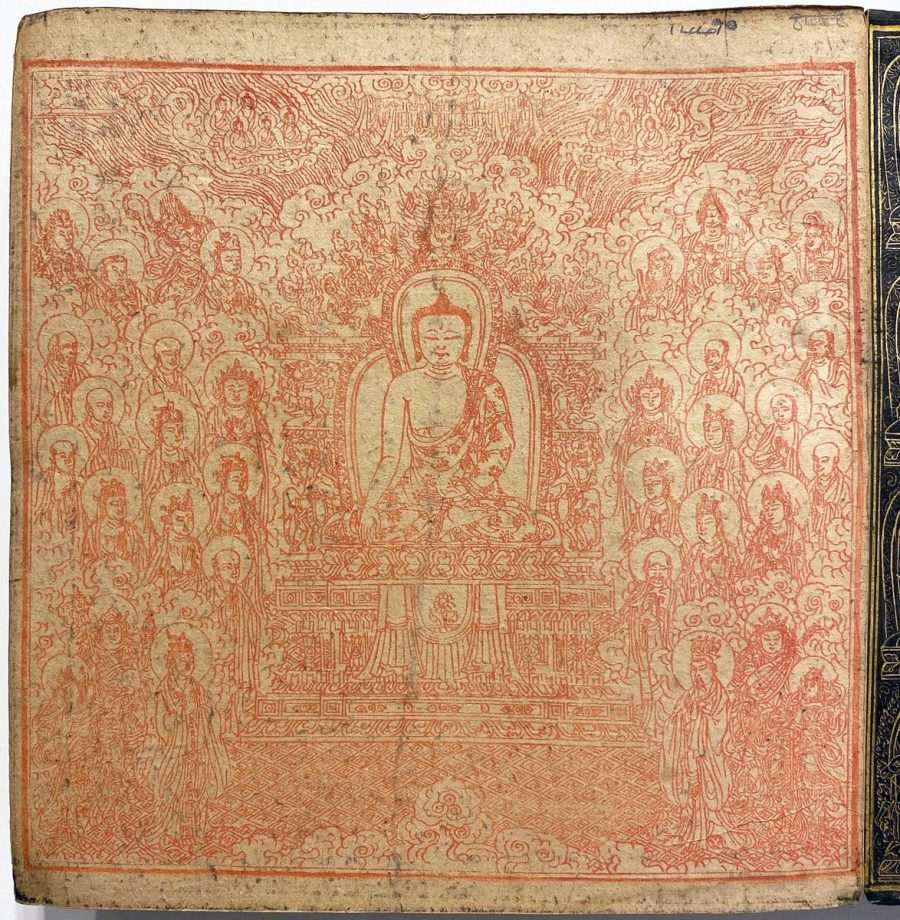

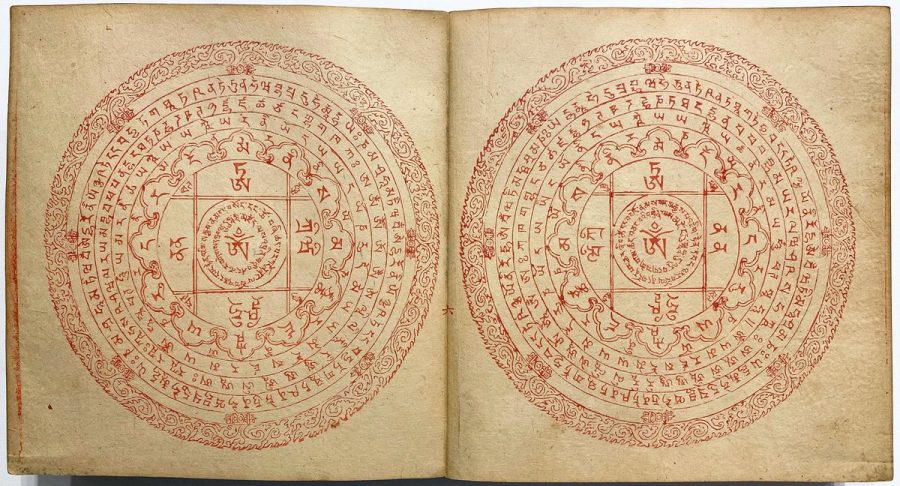

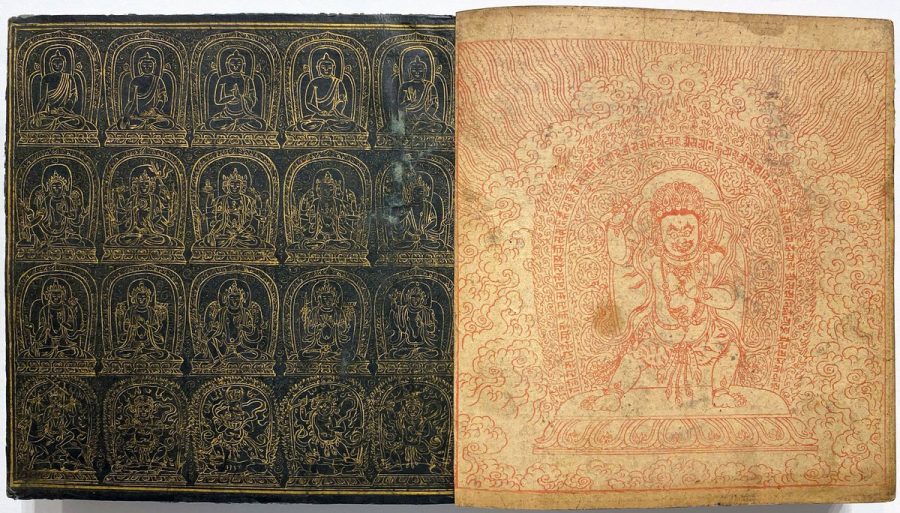

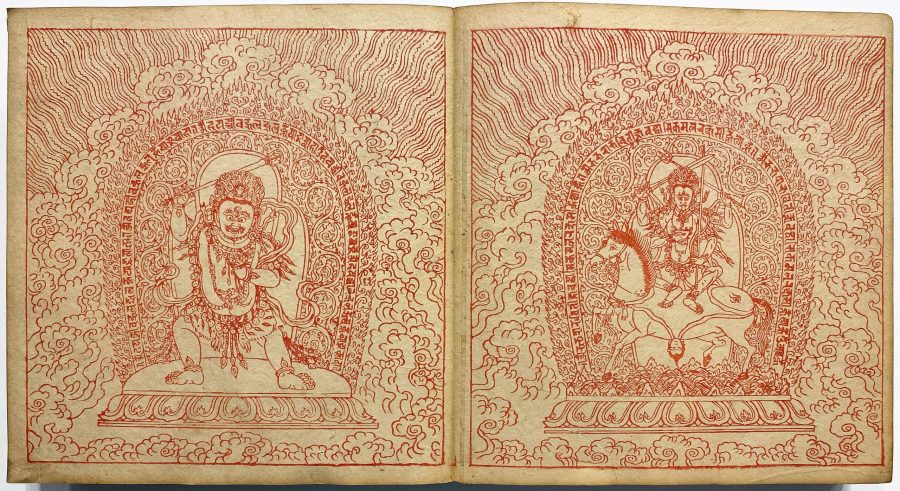

The Gutenberg Bible went to press in the year 1454. We now see it as the first piece of mass media, printed as it was with the then-cutting-edge technology of metal movable type. But in the history of aesthetic achievements in book-printing, the Gutenberg Bible wasn't without its precedents. To find truly impressive examples requires looking in lands far from Europe: take, for instance, this "Sino-Tibetan concertina-folded book, printed in Beijing in 1410, containing Sanskrit dh?ran?s and illustrations of protective mantra-diagrams and deities, woodblock-printed in bright red ink on heavy white paper," whose "breathtakingly detailed printing" predates Gutenberg by 40 years.

That description comes from a Twitter user called Incunabula (a term referring to early books), a self-described bibliophile and rare book collector who posts about "the history of writing, and of the book, from cave painting to cuneiform tablet to papyrus scroll to medieval codex to Kindle."

Incunabula's six-tweet thread on this early 15th-century Sino-Tibetan book includes both pictures and descriptions of this remarkable artifact's interior and exterior.

Its text, written in the Tibetan and Nepalese Rañjan? script, "is printed twice, once on each side of the paper, so that the book may be read in the Indo-Tibetan manner by turning the pages from right to left or in Chinese style by turning from left to right." The book's content is "a sequence of Tibetan Buddhist recitation texts," or chants, all "protected at front and back by thicker board-like wrappers," each "covered in fine pen-drawings in gold paint on black of 20 icons of the Tath?gatas."

Incunabula has also posted extensively about Buddhist texts from other times and lands: a Thai folding manuscript from the mid-19th century telling of a monk's journeys to heaven and hell; a Mongolian manuscript from the same period that translates the ?oyijod Dagini, "a popular Buddhist text about virtue, sin and the afterlife"; an example of "Japanese Buddhist printing 150 years before Gutenberg"; an "8th century Khotanese amuletic scroll from the Silk Road." The creators of these texts would have meant the words they were preserving to survive them — but our marveling at them hundreds, even more than a thousand years later, would surely have come as a surprise.

Related Content:

The World’s Largest Collection of Tibetan Buddhist Literature Now Online

Free Online Course: Robert Thurman’s Introduction to Tibetan Buddhism (Recorded at Columbia U)

Tibetan Musical Notation Is Beautiful

Oxford University Presents the 550-Year-Old Gutenberg Bible in Spectacular, High-Res Detail

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Breathtakingly-Detailed Tibetan Book Printed 40 Years Before the Gutenberg Bible is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2T79FqZ

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment