Two pieces of reading advice I’ve carried throughout my life came from two early favorite writers, Herman Melville and C.S. Lewis. In one of the myriad pearls he tosses out as asides in his prose, Melville asks in Moby Dick, “why read widely when you can read deeply?” Why spread our minds thin? Rather than agonize over what we don’t know, we can dig into the relatively few things we do until we’ve mastered them, then move on to the next thing.

Melville’s counsel may not suit every temperament, depending on whether one is a fox or a hedgehog (or an Ahab). But Lewis’ advice might just be indispensable for developing an outlook as broad-minded as it is deep. “It is a good rule,” he wrote, “after reading a new book, never to allow yourself another new one till you have read an old one in between. If that is too much for you, you should at least read one old one to every three new ones.”

Many other famous readers have left behind similar pieces of reading advice, like Edward Bulwer-Lytton, author of notorious opener “It was a dark and stormy night." As though refining Lewis’ suggestion, he proposed, “In science, read, by preference, the newest works; in literature, the oldest. The classic literature is always modern. New books revive and redecorate old ideas; old books suggest and invigorate new ideas.”

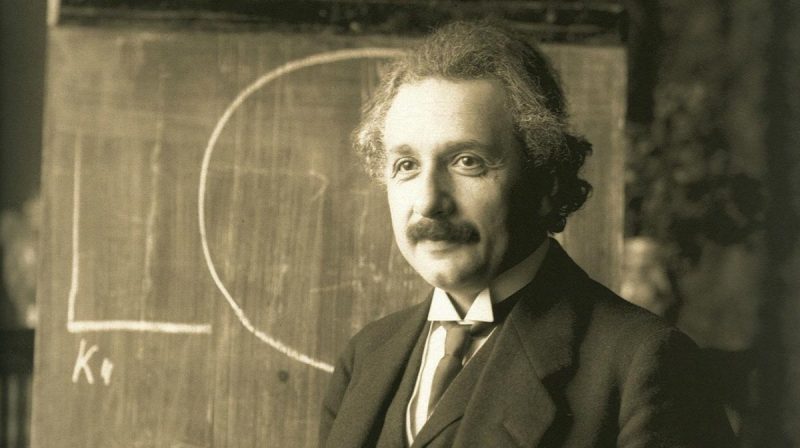

Albert Einstein shared neither Lewis’ religion nor Bulwar-Lytton’s love of semicolons, but he did share both their outlook on reading the ancients. Einstein approached the subject in terms of modern arrogance and ignorance and the bias of presentism, writing in a 1952 journal article:

Somebody who only reads newspapers and at best books of contemporary authors looks to me like an extremely near-sighted person who scorns eyeglasses. He is completely dependent on the prejudices and fashions of his times, since he never gets to see or hear anything else. And what a person thinks on his own without being stimulated by the thoughts and experiences of other people is even in the best case rather paltry and monotonous.

There are only a few enlightened people with a lucid mind and style and with good taste within a century. What has been preserved of their work belongs among the most precious possessions of mankind. We owe it to a few writers of antiquity (Plato, Aristotle, etc.) that the people in the Middle Ages could slowly extricate themselves from the superstitions and ignorance that had darkened life for more than half a millennium.

Nothing is more needed to overcome the modernist's snobbishness.

Einstein himself read both widely and deeply, so much so that he “became a literary motif for some writers,” as Dr. Antonia Moreno González notes, not only because of his paradigm-shattering theories but because of his generally well-rounded public genius. He was frequently asked, and happy to volunteer, his “ideas and opinions”—as the title of a collection of his writing calls his non-scientific work, becoming a public philosopher as well as a scientist.

We might credit Einstein's liberal attitude towards reading and education—in the classical sense of the word "liberal"— as a driving force behind his endless intellectual curiosity, humility, and lack of prejudice. His diagnosis of the problem of modern ignorance may strike us as grossly understated in our current political circumstances. As for what constitutes a "classic," I like Italo Calvino's expansive definition: "A classic is a book that has never finished saying what it has to say."

via Mental Floss

Related Content:

Italo Calvino Offers 14 Reasons We Should Read the Classics

Virginia Woolf Offers Gentle Advice on “How One Should Read a Book”

The New York Public Library Creates a List of 125 Books That They Love

100 Novels All Kids Should Read Before Leaving High School

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Albert Einstein Explains Why We Need to Read the Classics is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2XGQLbO

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment