When Nikola Tesla Claimed to Have Invented a “Death Ray,” Capable of Destroying Enemies 250 Miles Away & Making War Obsolete

Just last week I visited Niagara Falls and beheld the noble-looking statue of Nikola Tesla installed there. It struck me as a fitting tribute to the inventor of the Death Ray. But then, its presence probably had more to do with Tesla’s having advised the builders of the falls’ power plant to use two-phase alternating current, the form of electricity of which he’s now remembered as a pioneer. And in any case, Tesla never actually invented a death ray, or at least he never demonstrated one. He did, however, claim to have been working on a system he called “teleforce,” which shot what he described as a “death beam” — rays, he insisted, would never be feasible — both “thinner than a hair” and powerful enough to “destroy anything approaching within 200 miles,” making warfare effectively obsolete.

These pronouncements attracted special media attention in the 1930s. “Hype about the weapon really took off in the run-up to World War II as Nazi Germany assembled a fearsome air force,” writes Sam Kean at the Science History Institute. “People in Tesla’s homeland, then called Yugoslavia, begged him to return home and install the rays to protect them from the Nazi menace.” But no known evidence suggests that the elderly Tesla had figured out how to actually make teleforce work.

At that point he had more pressing problems, not least the cost of the hotels in which he lived. “In 1915, his famous Wardenclyffe tower plant was sold to help pay off his $20,000 debt at the Waldorf-Astoria,” writes Mental Floss’ Stacy Conradt, and later he racked up a similarly large bill at the Governor Clinton. “He couldn’t afford the payment, so instead, Tesla offered the management something priceless: one of his inventions.”

That “invention” may have been the box examined after Tesla’s death in 1943 by physicist John G. Trump (uncle of former President Donald Trump). Left in a hotel vault, it was rumored to be “a prototype of his death ray.” Tesla had included a note, writes Kean, that “claimed the prototype inside was worth $10,000. More ominously, it said the box would detonate if opened incorrectly.” But when “the physicist steeled himself and began tearing off the brown paper,” he “must have laughed at what he saw underneath: a Wheatstone bridge, a tool for measuring electrical resistance. It was a common, mundane device — some old junk, really. It was certainly not a death ray, not even close.”

Though it must have been as powerful a disappointment as it was a relief, did that discovery prove that Tesla never invented a death ray? The U.S. government didn’t take its chances on the matter: as History.com’s Sarah Pruitt tells it, agents “swooped in and took possession of all the property and documents from his room at the New Yorker Hotel” right after Tesla’s death. And “while the FBI originally recorded some 80 trunks among Tesla’s effects, only 60 arrived in Belgrade,” home of the Nikola Tesla Museum, nearly a decade later. The idea of death rays has long survived Tesla himself, taking on forms from the Reagan administration’s “Star Wars” nuclear defense program to the military laser weapons tested in recent years. Few such technologies seem capable of ending all war, as Tesla promised. But if one ever does, we could honor his memory by referring to it, in the manner he preferred, as not a death ray but a death beam.

Related Content:

In 1926, Nikola Tesla Predicts the World of 2026

The Electric Rise and Fall of Nikola Tesla: As Told by Technoillusionist Marco Tempest

Nikola Tesla Accurately Predicted the Rise of the Internet & Smart Phone in 1926

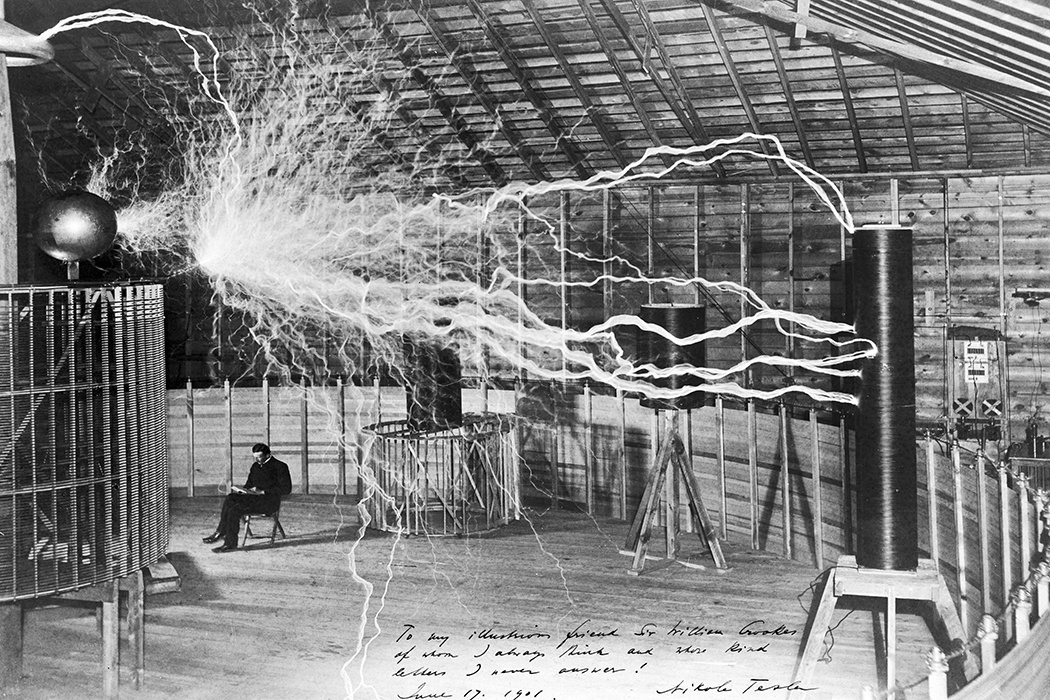

Mark Twain Plays With Electricity in Nikola Tesla’s Lab (Photo, 1894)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

When Nikola Tesla Claimed to Have Invented a “Death Ray,” Capable of Destroying Enemies 250 Miles Away & Making War Obsolete is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3bOIkCH

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment