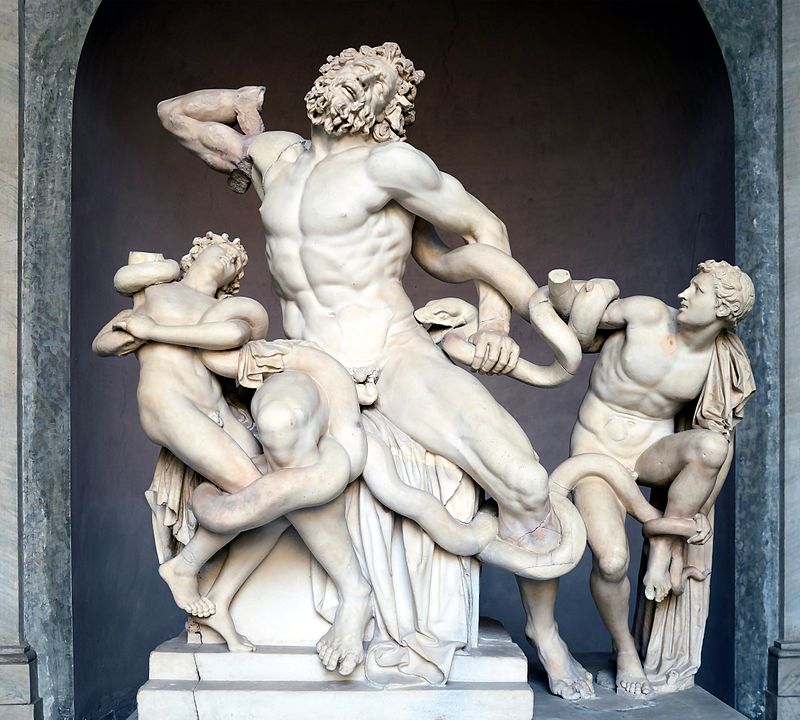

Not many ancient statues are as well-known as Laocoön and His Sons. Masterfully sculpted some time between the first century BC and the first century AD, it depicts the eponymous Trojan priest in an agonizing struggle with the serpents that will kill one or both of his sons. The details of the tale vary depending on the teller: Virgil describes Laocoön as a priest of Poseidon who dared to attempt exposing the famous Trojan Horse ruse, and Sophocles describes him as a priest of Apollo who violated his vow of celibacy. Whichever version of the story he heard, the sculptor clearly drew from it powerful enough inspiration to impress Pliny the Elder, in whose Natural History the piece figures.

Even among the more artistically sophisticated beholders of the Renaissance, Laocoön and His Sons proved a captivating piece of work. Unearthed from a Roman vineyard in 1506, it looked to have weathered the intervening millennium and half with much less wear and tear than most large artifacts from antiquity — though Laocoön himself was, conspicuously, missing an arm. Commissioned by Pope Julius II, Vatican architect Donato Bramante “held a contest to see who could come up with the best version of the arm restoration,” writes Kaushik Patowary at Amusing Planet. “Michelangelo suggested that Laocoön’s missing arm should be bent back as if the Trojan priest was trying to rip the serpent off his back.”

Michelangelo wasn’t the only Renaissance man in competition: “Raphael, who was a distant relative of Bramante, favored an extended arm. In the end, Jacopo Sansovino was declared the winner, whose version with an outstretched arm aligned with Raphael’s own vision of how the statue should look.” Laocoön was thus eventually restored with his arm outstreched, and kept that way until, “in a strange twist of fate, an antique backward-bent arm was discovered in a Roman workshop in 1906, a few hundred meters from where the statue group had been found four hundred years earlier.” Positioned just as Michelangelo had suggested, this disembodied marble limb turned out unmistakably to have come from Laocoön and His Sons — but about three and a half centuries too late, alas, for Michelangelo to lord it over Raphael.

Related Content:

A Creepy 19th Century Re-Creation of the Famous Ancient Roman Statue, Laocoön and His Sons

Michelangelo’s David: The Fascinating Story Behind the Renaissance Marble Creation

New Video Shows What May Be Michelangelo’s Lost & Now Found Bronze Sculptures

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Michelangelo Entered a Competition to Put a Missing Arm Back on Laocoön and His Sons — and Lost is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook and Twitter, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3k6pL1n

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment