The Sublime Alice in Wonderland Illustrations of Tove Janssen, Creator of the Globally-Beloved Moomins (1966)

Sometimes describing a classic work of literature as “timeless” draws attention, when we revisit it, to how much it is bound up with the conventions of its time. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland emerged from a very specific time and place, the bank of the Thames in 1862 where Charles Lutwidge Dodgson first composed the tale for Alice Liddell and her sister. The future Lewis Carroll’s future bestseller became one of the most widely adapted and adopted works of literature in history. It never needs to be revived—Alice is always contemporary.

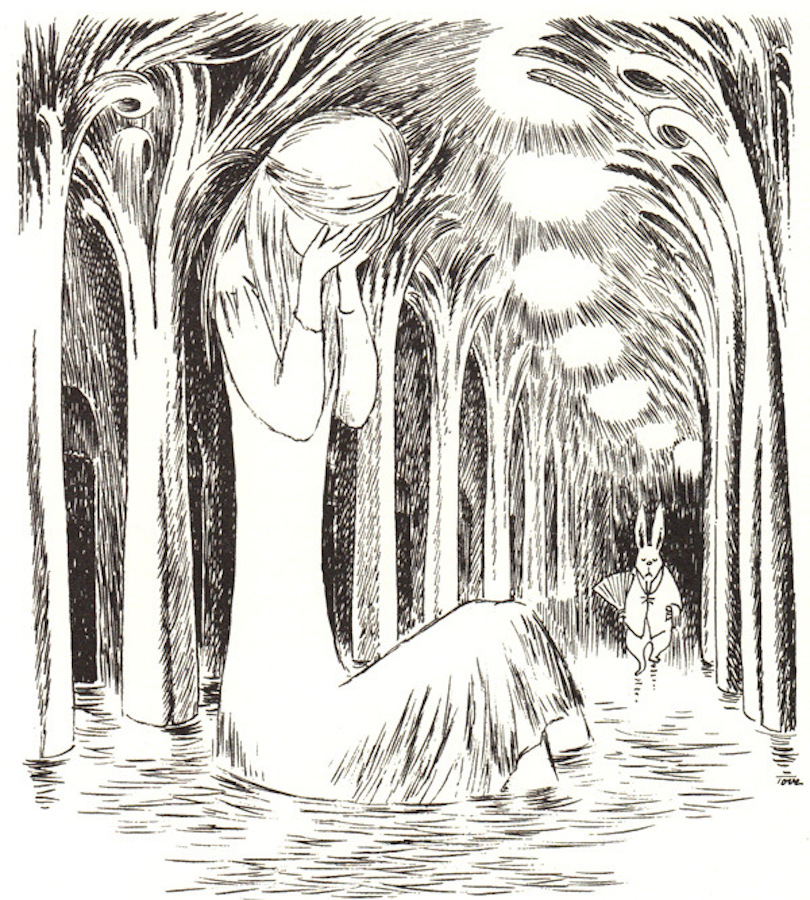

Those who have read the book to children know that Carroll’s nonsense story, though filled with archaic terms and outdated ideas about education, requires little additional explanation: indeed, it cannot be explained except by reference to the strange leaps of logic, rapid changes in scale and direction, and anthropomorphism familiar to everyone who has had a dream. Dodgson was a pretty weird character, and prim Victorian Alice is not exactly an everygirl, but every reader imagines themselves tumbling right down the rabbit hole after her.

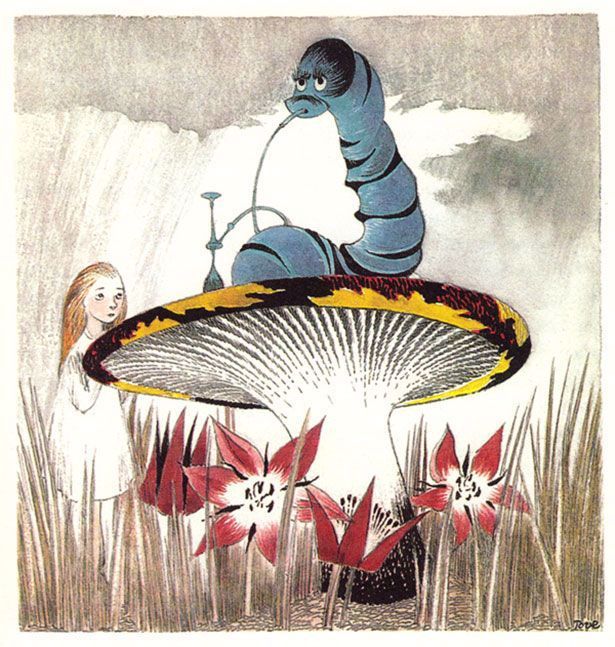

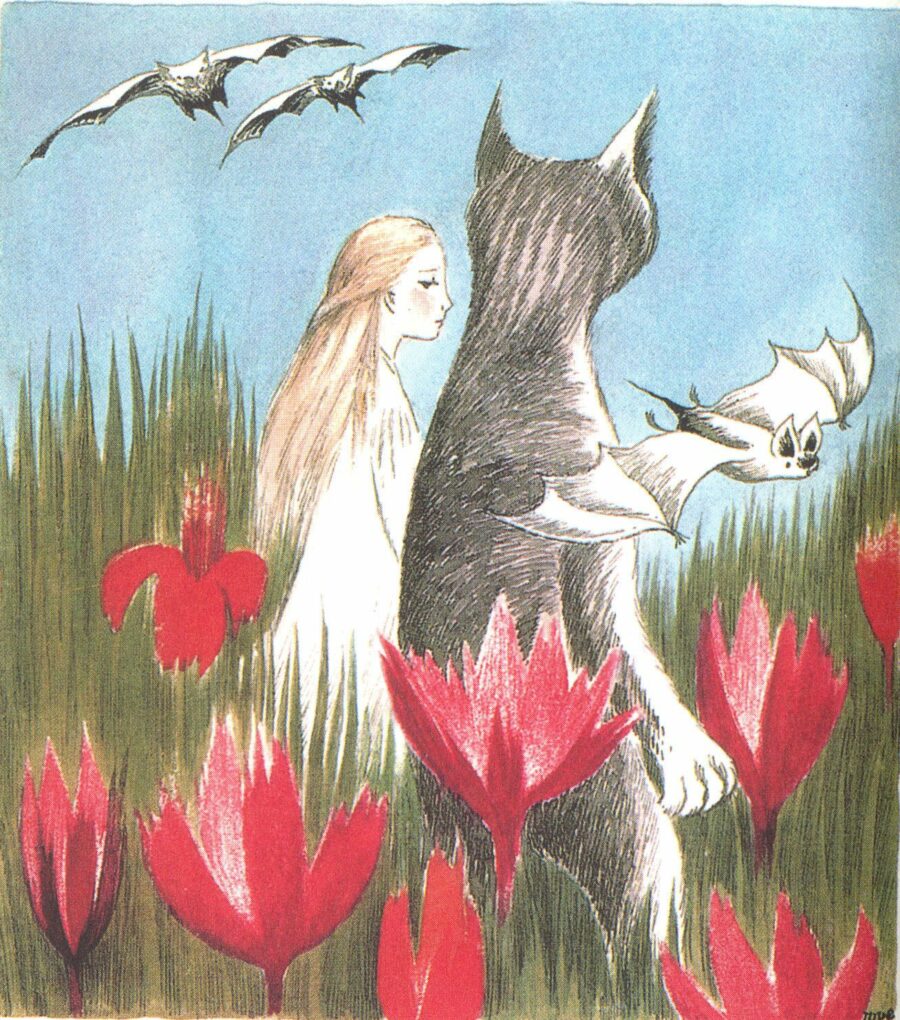

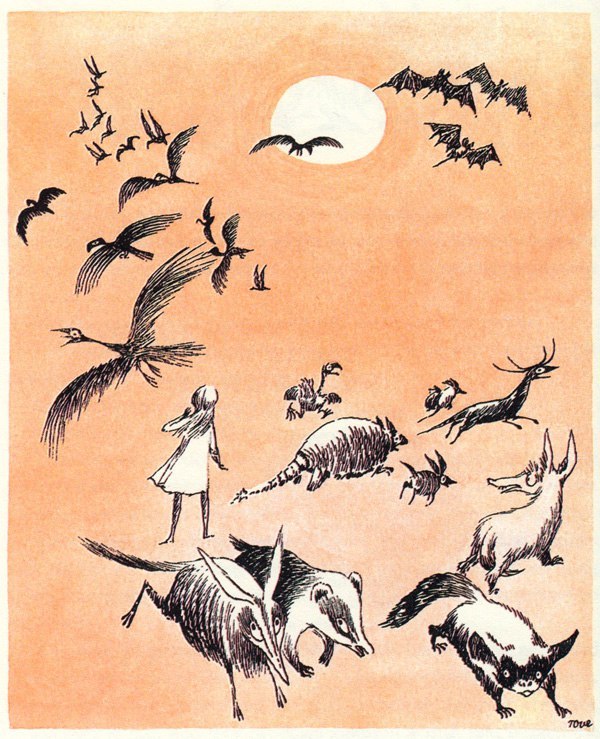

As far as illustrators of Carroll’s timeless classic go, it’s hard to find one who is more universally beloved, and more Alice-like, than Tove Jansson, inventor of the Moomins, the Finnish series of children’s books and TV shows that is, in parts of the world, like a religion. How are her Alice illustrations not better known? It’s hard to say. Janssen’s Bohemian biography is as endearing as her characters, and she would make a wonderful subject for a children’s story herself. As James Williams tells it at Apollo Magazine:

The artist, Tove Jansson (1914–2001), was a great colourist who lived a richly plural life. Born into Finland’s Swedish-speaking minority to a Swedish mother and a Finnish father, both artists, she grew up on both sides of the Baltic. Jansson trained as a painter and illustrator in Stockholm and Paris, and made an early living through commissions and piecework. She was an acerbic and witty anti-fascist cartoonist during the Second World War, sending up Hitler and Stalin in covers for the Swedish-language periodical Garm. Descended on the one hand from a famous preacher, and on the other from a pioneer of the Girl Guide movement, she was raised on the Bible and on tales of adventure (Tarzan, Jules Verne, Edgar Allen Poe). In her thirties she built a log cabin on an island and was a capable sailor. She lived visibly and courageously with her partner, the Finnish artist Tuulikki Pietilä, at a time when lesbian relationships did not enjoy public acceptance. She considered emigrating at various times to Tonga and Morocco but, despite travelling widely, remained rooted in Finland where she became (dread accolade) a ‘national treasure.’ She wrote a picture book for children about the imminent end of the world and spare, tender fiction for adults about love and family. She never stopped drawing and painting. She was Big in Japan.

We’ll find dream logic woven into all of Janssen’s work, from her early Moomin-like creature paintings from the 1930s to her illustrations for The Hobbit and Alice decades later. Her Alice, in Swedish, was first published in 1966, then released in an American edition in 1977. Sadly, her illustrations “did not receive such a great reception,” notes Moomin.com. “Readers already had their own imaginations in their minds about these classics.”

Blame Disney, I suppose, but there is never a bad time to re-imagine Alice’s journey, and the artist has left us with an excellent way to do so, “crafting a sublime fantasy experience,” Maria Popova writes, “that fuses Carroll’s Wonderland with Jansson’s Moomin Valley.” See more of Jansson’s timelessly weird drawings at Brain Pickings.

Related Content:

The First Film Adaptation of Alice in Wonderland (1903)

Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, Illustrated by Salvador Dalí in 1969, Finally Gets Reissued

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The Sublime Alice in Wonderland Illustrations of Tove Janssen, Creator of the Globally-Beloved Moomins (1966) is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3oHGZTu

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment