What is the musical instrument most thoroughly of the 1980s? Many would say the "keytar," a class of synthesizer keyboards shaped and worn like a guitar. Their relatively light weights and affordable prices, even when first brought to market, put keytars within the reach of musicians who wanted to possess both the wide sonic palette of digital synthesis and the inherent cool of the guitarist. This arrangement wasn't without its compromises: few keytar players enjoyed the full range of that sonic palette, to say nothing of that cool. But in 1985, a new hope appeared for the synthesizer-envying guitarist and guitar-envying synthesist alike: the SynthAxe.

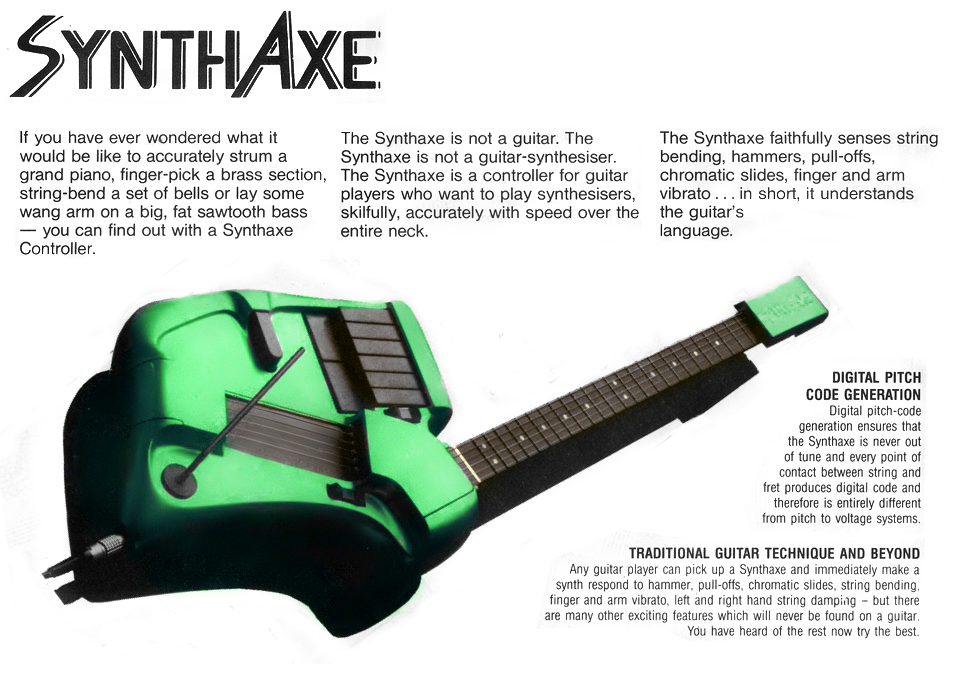

Created by English inventors Bill Aitken, Mike Dixon, and Tony Sedivy (and funded in part by Richard Branson's Virgin Group), the SynthAxe made a quantum leap in the development of synthesizer-guitars, or guitar-synthesizers. Unlike a keytar, it used actual strings — not just one but two independent sets of them — that when played could control any synthesizer compatible with the recently introduced Musical Instrument Digital Interface (MIDI) standard.

As Guitarist magazine editor Neville Marten demonstrates in the contemporary promotional video at the top of the post, this granted anyone who could play the guitar command of all the sounds cutting-edge synthesizers could make.

Not that mastery of the guitar translated immediately into mastery of the SynthAxe: even the most proficient guitarist had to get used to the unusually sharp angle of its neck, its evenly spaced frets, and the set of keys embedded in its body. ("That is the point, it’s not a guitar," as Aitken took pains to explain.) You can see Lee Ritenour make use of both the SynthAxe's strings and keys in the 1985 concert clip above. Nicknamed "Captain Fingers" due to his sheer dexterity, Ritenour had been in search of ways to expand his sound, experimenting with guitar-synthesizer hybrid systems even in the 70s. When the SynthAxe came along, not only did he record a whole album with it, that album's cover is a painting of him with the striking new instrument in hand.

So is the cover of Atavachron, the first album Allan Holdsworth recorded after meeting the SynthAxe's creators at a trade show. No guitarist would take up the SynthAxe with the same fervor: Holdsworth, seen playing it with a breath controller (!) in the clip above, would continue to use it on his recordings up until his death in 2017. "People used to write notes on my amp, asking me to stop playing the SynthAxe and play the guitar instead," he told Guitar World in his final interview that year. "But now people often ask me, 'We'd love to hear you play the SynthAxe — did you bring it?' I rarely play it onstage anymore because it's too costly to take on the road and it requires a lot of equipment."

The amount of associated gear no doubt put many an aspiring synthesizer-guitarist off the SynthAxe. ("It's about as portable as a drum kit isn't," writes early adopter John Hollis.) So must the price tag, a cool £10,000 back in 1985. This didn't put off guitarist Alec Stansfield, whose enthusiasm for the SynthAxe as was such that he joined the company, having "knocked long and hard on their door until they gave me a job as a production engineer." Alas, he writes, "the instrument was never a commercial success and eventually the company ceased trading. Fewer than 100 instruments had been produced in total. In the final months I was paid with a SynthAxe system since cash was tight" — a system he shows off in the video above.

Stansfield sold off his SynthAxe in 2013, but what has become of the others? One of Ritenour's SynthAxes eventually found its way into the possession of Roy Wilfred Wooten, better known as Future Man of Béla Fleck and the Flecktones. "Over a period of time, he began modifying it into an almost entirely new instrument: the SynthAxe Drumitar," writes Computer History Museum curator Chris Garcia. "This system, which replaced the strings as the primary triggering mechanism, allowed Wooten to play the 'drums' using the guitar-like device." In the concert clip just above, you can behold Future Man playing and explaining this "SynthAxeDrumitar," sounds like a drum kit but looks like a guitar — though rather vaguely, at this point. Call it SynthAxe-meets-Mad Max.

Related Content:

Behold the First Electric Guitar: The 1931 “Frying Pan”

Brian May’s Homemade Guitar, Made From Old Tables, Bike and Motorcycle Parts & More

Hear Musicians Play the Only Playable Stradivarius Guitar in the World: The “Sabionari”

The Nano Guitar: Discover the World’s Smallest, Playable Microscopic Guitar

How the Yamaha DX7 Digital Synthesizer Defined the Sound of 1980s Music

Everything Thing You Ever Wanted to Know About the Synthesizer: A Vintage Three-Hour Crash Course

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

The Story of the SynthAxe, the Astonishing 1980s Guitar Synthesizer: Only 100 Were Ever Made is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3dgmA2z

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment