The 1937 Experiment in Distance Learning: When Chicago Schools Went Remote, Over Radio, During a Polio Outbreak

As all of us have noticed in recent months, living in a viral pandemic really messes with your sense of time. A few months feels like a decade. Time slows to a crawl. If you’re a parent, however, you have before you walking, talking, growing, complaining reminders that no matter what’s happening in the world, children still grow up just the same. They need new experiences and new clothes just as before, and they need to keep their brains engaged and try, at least, to build on prior knowledge.

Maybe we’re learning new things, too. (Adult brains also need exercise.) Or not. We have some control over the situation; kids don’t. “Learning loss” over inactive months is real, and the government still has the responsibility (for what the word is worth) to educate them. Online learning may feel like a bad compromise for many families, and its success seems largely dependent—as in regular school—on parent involvement and access to resources. But it’s better than eight months of the more mindless kind of screen time.

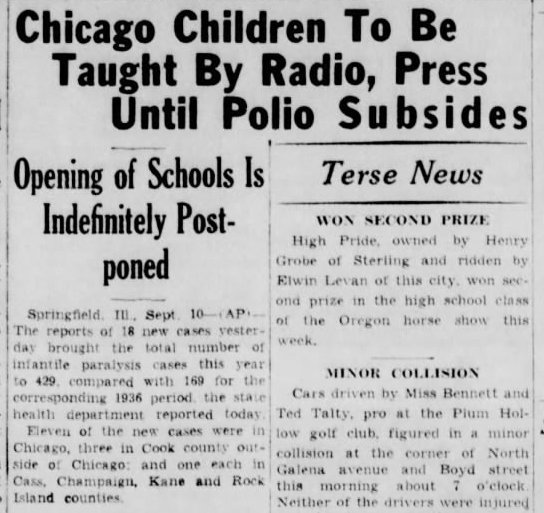

It may help to know that remote learning isn’t new, even if we’re still adjusting to technology that lets teachers (and bosses) into our homes with cameras and microphones. The challenges “may seem unprecedented,” Stanford professor Michael Hines writes at The Washington Post, but “educators may be surprised to learn that almost 100 years ago Chicago’s schools faced similar circumstances” during the polio epidemic and met them in a similar way. In 1937, an outbreak forced the city to close schools, and prompted “widespread alarm about lost instructional time and students left to their own devices" (so to speak).

Administrators were “determined to continue instructions for the district’s nearly 325,000 elementary age students” through the only remote technology available, radio, “still fairly new and largely untested in education in the 1930s.” According to Hines, a historian of education in the U.S., the program was very well organized, the lessons were engaging, and educators “actively sought to involve parents and communities” through telephone hotlines they could call with questions or comments. On the first day, they logged over 1,000 calls and added five additional teachers.

You might be wondering—given digital divide problems of online learning today—whether all the students served actually owned a radio and telephone. Katherine Foss, a professor of Media Studies at Middle Tennessee State University, notes that in the late 1930s, “over 80% of U.S. households owned at least one radio, though fewer were found in homes in the southern U.S., in rural areas and among people of color.” Those who didn't were left out, and school authorities had no way to track attendance. “Access issues received little attention” in the media. School Superintendent William Johnson had no idea how many students tuned in.

The local program lasted less than three weeks before schools reopened. Some felt the instruction moved too quickly and “students who needed more attention or remediation struggled through one-size-fits-all radio lessons,” notes Hines. Educators today will sympathize with the overall sense at the time that those who benefitted most from the radio lessons were students who needed them least.

Learn more about the experiment in Hines’ history lesson (also see Foss' recent article), and consider the lessons we can apply to the present. Remote education still has flaws, and parents still struggle to find time for involvement, but the technology has made it a viable option for much longer than three weeks, and maybe, given future uncertainties, far longer than that.

Related Content:

Dyson Creates 44 Free Engineering & Science Challenges for Kids Quarantined During COVID-19

Free Online Drawing Lessons for Kids, Led by Favorite Artists & Illustrators

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

The 1937 Experiment in Distance Learning: When Chicago Schools Went Remote, Over Radio, During a Polio Outbreak is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/36IlE64

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment