How the “First Photojournalist,” Mathew Brady, Shocked the Nation with Photos from the Bloodiest Battles of the Civil War

In her 1938 essay “Three Guineas,” Virginia Woolf wondered “whether when we look at the same photographs we feel the same things.” Woolf half-hoped that grisly images of the dead from the Spanish Civil War might help put an end to the spreading global conflict. She recognized, writes Susan Sontag in Regarding the Pain of Others, photography’s ability “to vivify the condemnation of war” and to “bring home, for a spell, a portion of its reality to those who have no experience of war at all.”

Mathew Brady, the man credited as the “father of photojournalism,” had no such lofty ambitions at the beginning of the Civil War. At first, he offered to photograph soldiers before they left for the battlefield, to preserve their pre-war image for posterity should they not return. (He cynically advertised his services with the line, “You cannot tell how soon it may be too late.”) Brady was already a successful photographer and had taken portraits of Abraham Lincoln, Andrew Jackson, Daniel Webster, and Edgar Allan Poe.

Having studied under Samuel Morse, who brought the daguerreotype technique to the U.S., Brady opened his first studio in New York in 1844 and became highly sought after. He might have safely waited out the war in the city, operating a thriving business, but, as he remembered later, “I had to go. A spirit in my feet said ‘Go,’ and I went.” Brady took his petition all the way to Lincoln, who approved it on the condition that Brady finance the documentation himself. “At his own expense,” notes the American Battlefield Trust, “he organized a group of photographers and staff to follow the troops as the first field-photographers.”

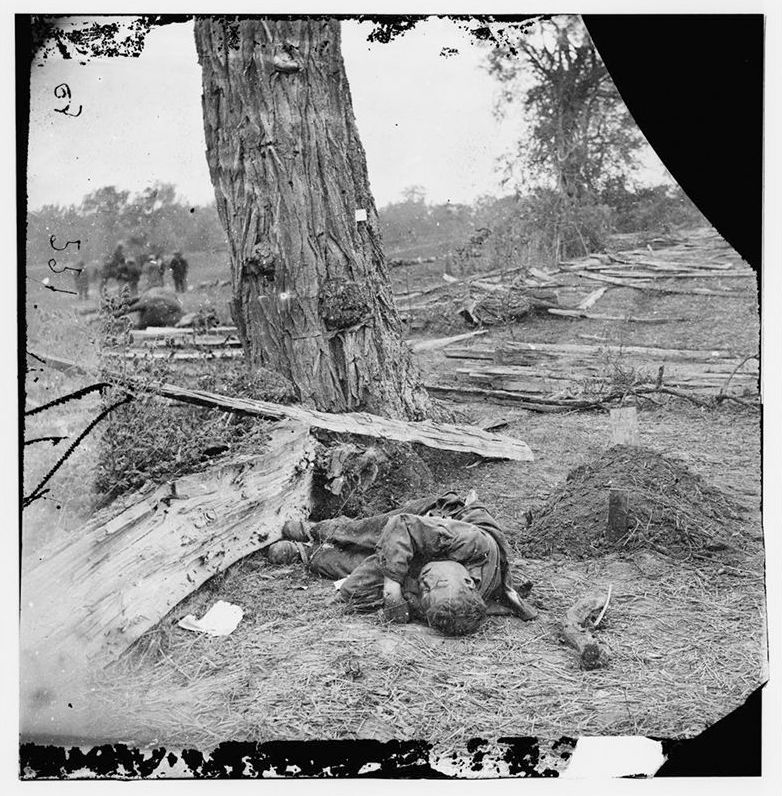

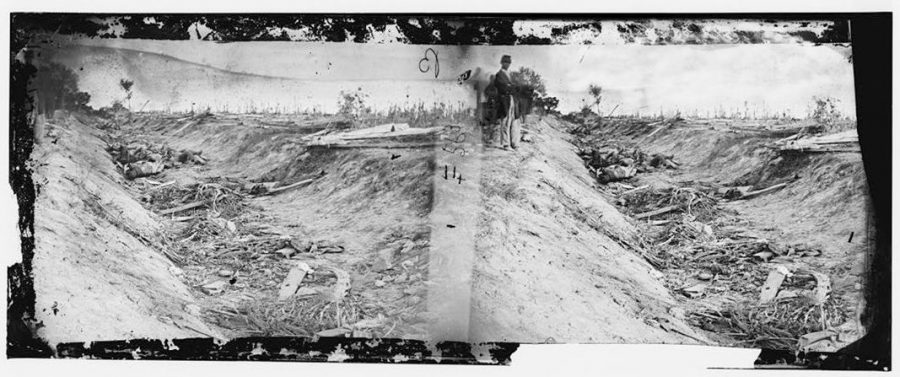

Soon after, “in 1862, Brady shocked the nation when he displayed the first photographs of the carnage of the war in his New York Studio in an exhibit entitled ‘The Dead of Antietam.’ These images, photographed by Alexander Gardner and James F. Gibson, were the first to picture a battlefield before the dead had been removed and the first to be distributed to a mass public.” The New York Times responded as Woolf would seventy-six years later, writing of the photos:

Mr. Brady has done something to bring home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war. If he has not brought bodies and laid them in our door-yards and along the streets, he has done something very like it.

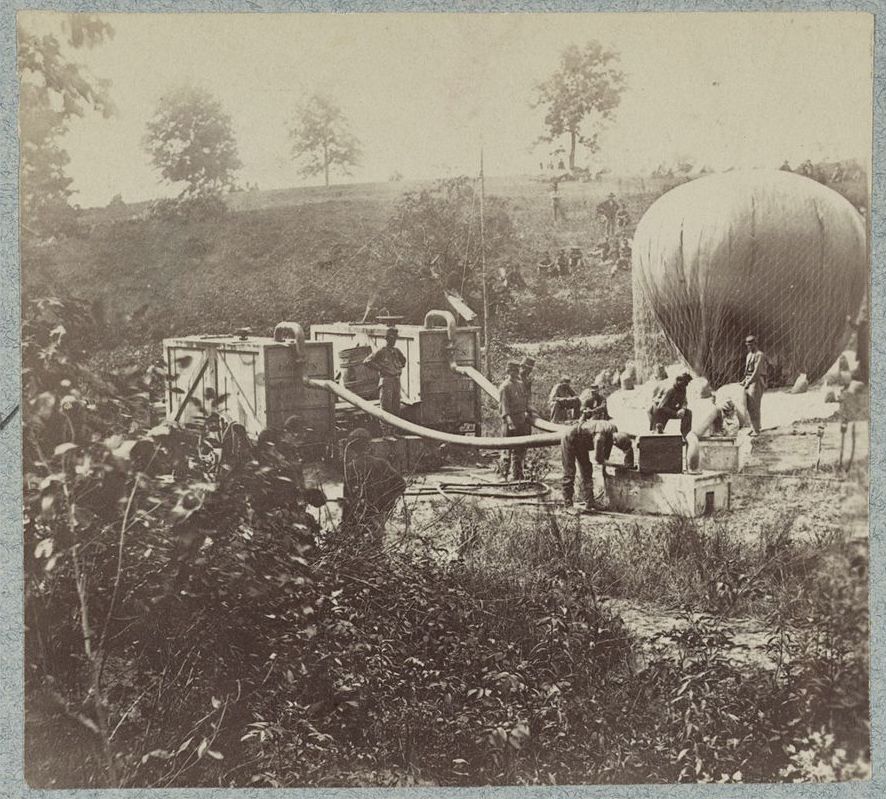

Shocked the nation may have been, but the war dragged on three more years. Brady and his team not only photographed the dead—they captured everything from hot-air balloons to pontoon bridges to breastworks to winter huts and wagon trains. Brady went bankrupt funding the making of over 10,000 plates, many of them harrowing depictions of the war’s brutality, before the U.S. government finally bought them for $25,000.

The Public Domain Review has another harrowing collection of Brady’s daguerreotypes—portraits he took before the war that have decayed and distorted, as have a great many of Brady’s photos of the war dead. These images “were extremely sensitive to scratches, dust, hair, etc, and particularly the rubbing of the glass cover if they glue holding it in place deteriorated.” Despite photographers’ promises to the contrary, “this fixing" of the image for posterity "was far from permanent.” See more of Brady’s Civil War photographs at the National Archives.

Related Content:

The Civil War & Reconstruction: A Free Course from Yale University

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

How the “First Photojournalist,” Mathew Brady, Shocked the Nation with Photos from the Bloodiest Battles of the Civil War is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/2MJJhzL

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment