An Introduction to Thought Forms, the Pioneering 1905 Theosophist Book That Inspired Abstract Art: It Returns to Print on November 6th

“It is sometimes difficult to appreciate the impact that the late-nineteenth century (and ongoing) occult movement called Theosophy had on global culture,” Mitch Horowitz writes in his introduction to the newly republished 1905 Theosophical book, Thought Forms. That impact manifested “spiritually, politically, and artistically” in the work of literary figures like James Joyce and William Butler Yeats and religious figures like Jiddu Krishnamurti, handpicked as a teenager by Theosophist leader Charles W. Leadbeater to become the group’s messianic World Teacher.

The Theosophical Society helped re-introduce Buddhism, or a newly Westernized version, to Western Europe and the U.S., publishing the 1881 “Buddhist Catechism” by Henry Steel Olcott, a former Colonel for the Union Army. Olcott co-founded the society in New York City in 1875 with Russian occultist Helena Blavatsky. Soon afterward, the group of spiritual seekers relocated to India. “Nearly a century before the Beatles’ trek to Rishikesh,” writes Horwitz, “Blavatsky and Olcott laid the template for the Westerner seeking wisdom in the East.”

Theosophy also had a significant influence on modern art, including the work of Wassily Kandinsky, until recently considered the first Abstract painter—that is until the paintings of Hilma af Klint came to be widely known. The reclusive Swedish artist, whom we’ve covered here a few times before, came first, though no one knew it at the time. After showing her revolutionary abstract work to philosopher and onetime German and Austrian Theosophical Society leader Rudolf Steiner, she was told to hide it for another fifty years.

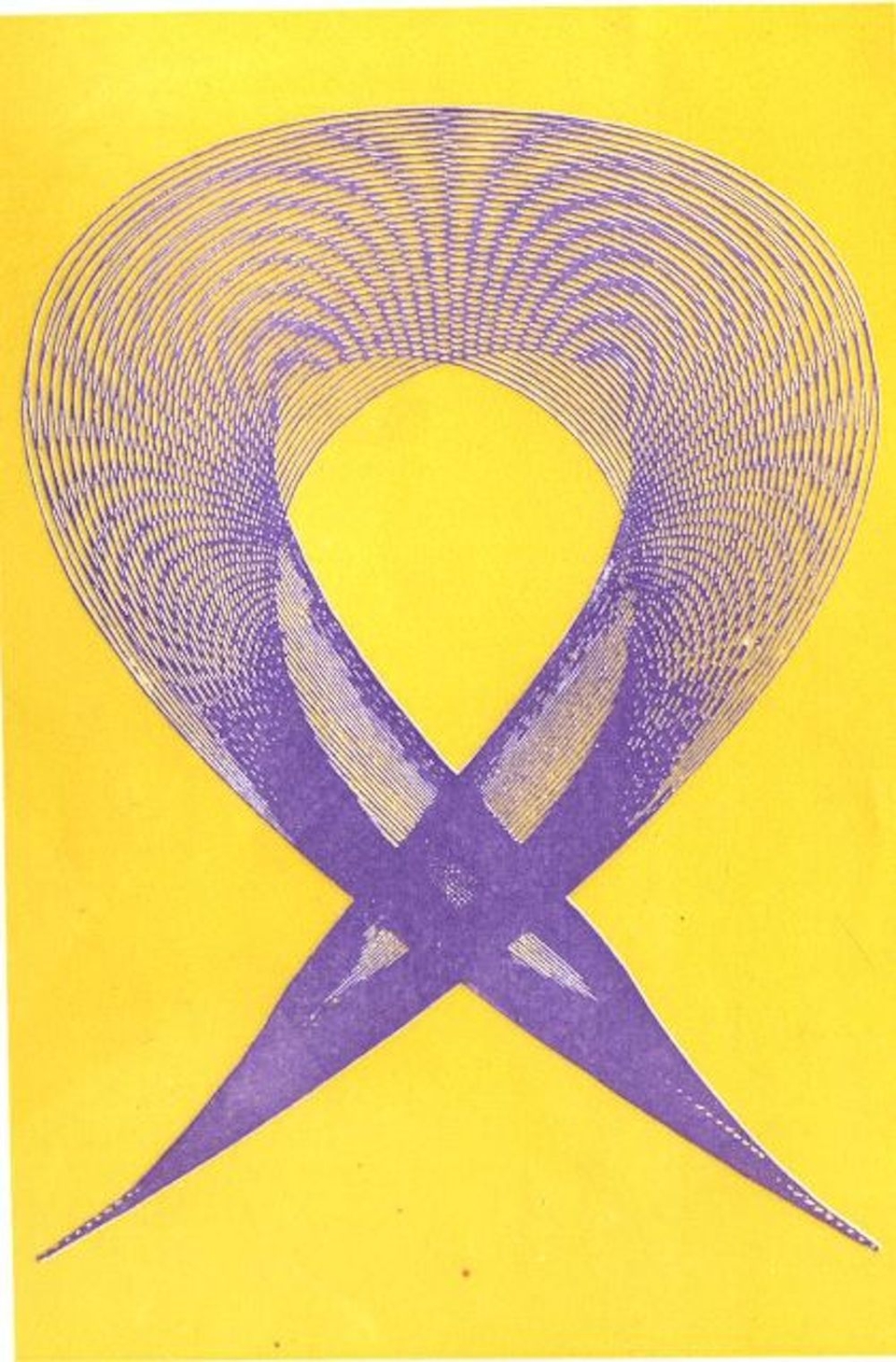

Theosophy gained many prominent converts in the UK, Europe, and around the world. Af Klint joined the Swedish society and remained a member until 1915. The symbolism in her mysterious abstractions, which she attributed to clairvoyant communication with “an entity named Amaliel,” may also have been suggested by the drawings in Thought Forms, an illustrated book created by Theosophical Society leaders Leadbeater and Annie Besant, who was “an early suffragist and political activist,” notes Sacred Bones Books. The small press will release a new edition of the book online and in stores on November 6. (See their Kickstarter page here and video trailer below.)

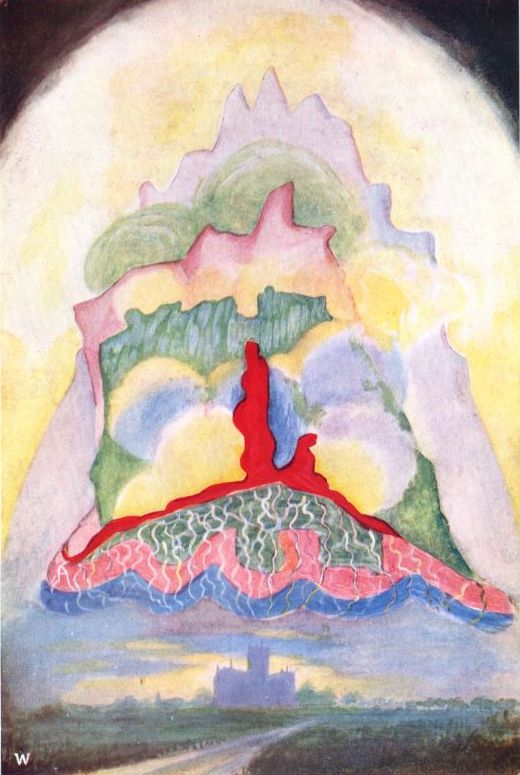

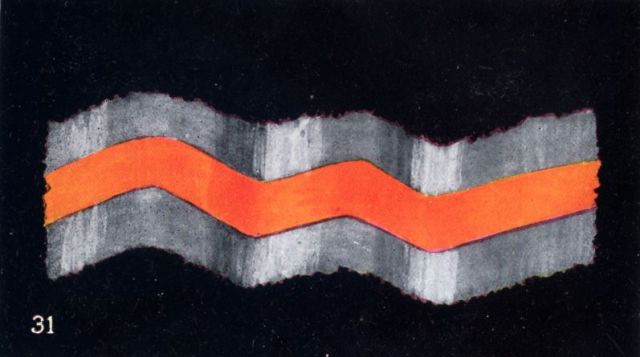

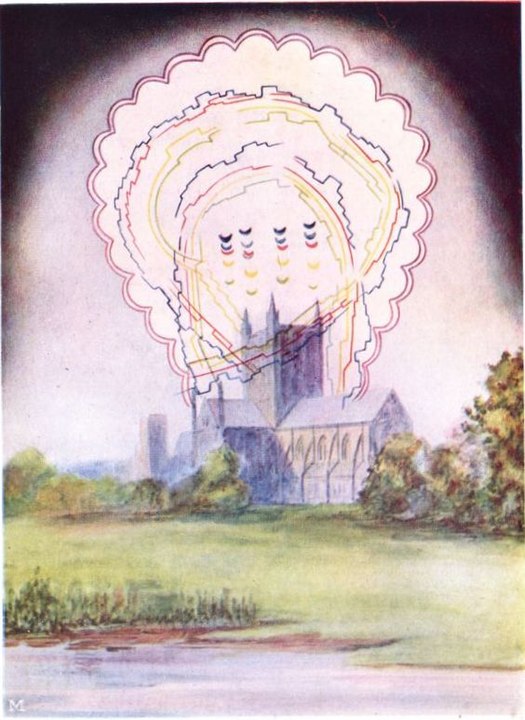

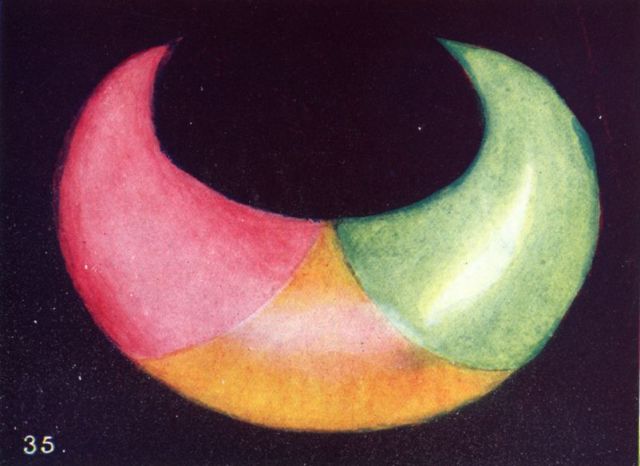

Besant was “far ahead of her time as an artist and thinker. Theosophy was the first occult group to open its doors to women and Thought Forms offers a reminder that the history of modernist abstraction and women’s contribution to it is still being written.” Although that unfolding history centrally includes af Klint and Besant, the latter did not actually make all of the illustrations we find in this strange book. She and Leadbeater claimed to have received, through clairvoyant means, “forms caused by definite thoughts thrown out by one of them, and also watched the forms projected by other persons under the influence of various emotions.”

So Besant would write in 1896 in the Theosophical journal Lucifer. After these “experiments,” the two then described going into trances and viewing “auras, vortices, etheric matter, astral projections, energy forms, and other expressions from the unseen world.” The two described these visions to a collection of visual artists, who rendered them into the paintings in the 1905 book.

Among those who do study the Theosophical Society’s impact, its first generation of publications—especially Olcott’s “Buddhist Catechism” and Blavatsky’s 1888 The Secret Doctrine—are especially well-known texts. But Thought Forms may prove “the most widely read, lasting, and directly influential book to emerge from the revolution that Theosophy ignited," Horowitz argues.

"By many estimates, Thought Forms marks the germination of abstract art”—originated through several artists' best guess at what visions of psychic phenomena might look like. You can follow Sacred Bones' Kickstarter campaign here.

Related Content:

Discover Hilma af Klint: Pioneering Mystical Painter and Perhaps the First Abstract Artist

New Hilma af Klint Documentary Explores the Life & Art of the Trailblazing Abstract Artist

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

An Introduction to Thought Forms, the Pioneering 1905 Theosophist Book That Inspired Abstract Art: It Returns to Print on November 6th is a post from: Open Culture. Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Google Plus, or get our Daily Email. And don't miss our big collections of Free Online Courses, Free Online Movies, Free eBooks, Free Audio Books, Free Foreign Language Lessons, and MOOCs.

from Open Culture https://ift.tt/3fvbJ4D

via Ilumina

Comments

Post a Comment